From its earliest origins to the dawn of civilization and beyond, Greek myth has never ceased to captivate writers, philosophers, and artists. It survived Roman conquests, barbarian invasions, Christian reinterpretations, and more, arriving down through the ages largely thanks to the works of painters and sculptors who immortalized its stories. From the Renaissance onward, gods, heroes, and ancient figures reemerged, rediscovered and celebrated for their feats or their political, ethical, and moral significance. Let’s explore some of the most famous masterpieces dedicated to classical mythology.

Hercules: the hero par excellence

Hercules is the quintessential hero, symbolizing strength and resilience, as well as the triumph of Good over Evil. Born from the union of Jupiter and Alcmene, he was despised by Juno from the start and punished with a terrible curse: in a fit of madness induced by the goddess, he killed his three children. To atone for this tragic crime, Hercules entered the service of the King of Tiryns, who made him carry out the proverbial Twelve Labors – trials of courage and intellect that he overcame, thus earning his place among the gods of Olympus.

In the 15th century, Hercules’s imagery spread to all major royal courts, thanks to his powerful, immediate symbolism. In Florence, he was an especially popular figure: even Michelangelo is said to have sculpted a snow statue of Hercules in 1494, placing it in the courtyard of Palazzo Medici.

However, few artists have portrayed Hercules more vividly and compellingly than Antonio del Pollaiolo, an excellent painter, goldsmith, and sculptor.

Ercole e l’idra and Ercole e Anteo by Pollaiolo

The two small panels depicting Ercole e l’idra and Ercole e Anteo (both from around 1475), today housed at the Gallerie degli Uffizi in Florence, along with a bronze sculpture of the same subject (ca. 1475, Museo del Bargello, Florence), are among the most iconic representations of the hero’s feats.

In the first painting, Hercules, dressed only in the lion skin – his typical attribute – lunges at the Hydra, a hideous seven-headed monster, to kill it with his club. His physical strength is evident in the pronounced musculature of his body, while his movement is highlighted by the billowing cloak and the snake-like forms of the beast. In the background, a marshland is depicted with remarkable detail, despite the panel’s small size (only 15×12 cm).It’s likely that this panel was once framed alongside Ercole e Anteo as a diptych. In this second painting, we see another of Hercules’s labors: the defeat of Antaeus, a giant who slaughtered men. Antaeus was the son of Gaia, the Earth goddess, and drew his immense strength from contact with the ground. After discovering his secret, Hercules lifts him up and crushes him in an inescapable grip. Observing the work, one can almost hear the giant’s cries of pain, while the powerful hero towers over a landscape painted from above – an artifice already familiar in Flemish painting.

Medusa, Perseus and Andromeda: a complex and fruitful myth

Equally valiant and famous is Perseus, the son of Jupiter and Danaë. After arriving with his mother at King Polydectes’s court, Perseus is given the suicidal mission of bringing back Medusa’s head. The most famous of the three Gorgons – with a woman’s face and snake hair – Medusa could turn anyone who gazed upon her to stone. With help from Minerva and Mercury, Perseus succeeds in his task and, on his way home, accomplishes yet another. Spotting the beautiful Andromeda chained to a rock and about to be devoured by a sea monster, he falls in love with her and decides to set her free by slaying the beast with his sword. He also uses Medusa’s severed head – still retaining its power – to eliminate Andromeda’s other suitors.Winged sandals, a curved sword, and sometimes a winged horse (Pegasus, born from the Gorgon’s severed head) are Perseus’s distinguishing traits, and his exploits have been depicted in a variety of ways and variations.

Testa di Medusa by Caravaggio

One truly feels petrified before Caravaggio’s masterpiece, Medusa (ca. 1598), originally created as a gift for Ferdinando I de’ Medici (Florence, Uffizi). Painted on a convex wooden shield, it shows the Gorgon’s face right after her decapitation, mouth agape in a silent scream, snake hair writhing. Caravaggio’s dramatic use of light and trademark realism heightens the work’s expressive force: the blood spurting from the neck, the terrified eyes, the living, pulsating vipers.

Medusa’s horror – killed by her own gaze reflected on Perseus’s shield – directly transmits to the viewer, who cannot escape its captivating, dangerous magnetism.

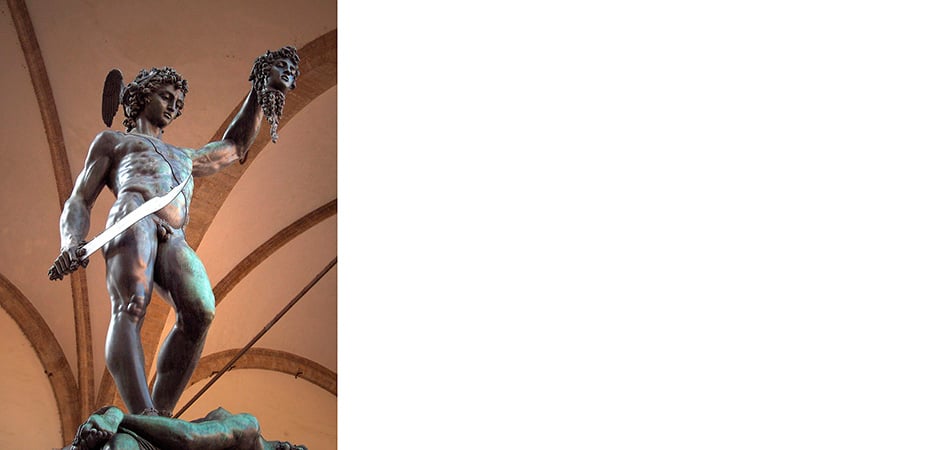

Perseo con la testa di Medusa by Benvenuto Cellini

Perseo con la testa di Medusa by Benvenuto Cellini is one of the most ambitious artistic and technical challenges of Mannerism. Standing nearly six meters tall including its decorated base, the bronze giant blends the muscular power reminiscent of Michelangelo with the refined detailing of a master goldsmith. In his autobiography, Cellini recounts the struggle against the material: facing technical problems, slander, and a casting process close to failing, he even melted down his own tin cookware to save the work. The result is truly extraordinary: the serpentine body of Perseus, the minutely detailed anatomy, and the dramatic realism of Medusa’s severed head still greet visitors in Florence’s Piazza della Loggia today.

Perseo libera Andromeda by Piero di Cosimo

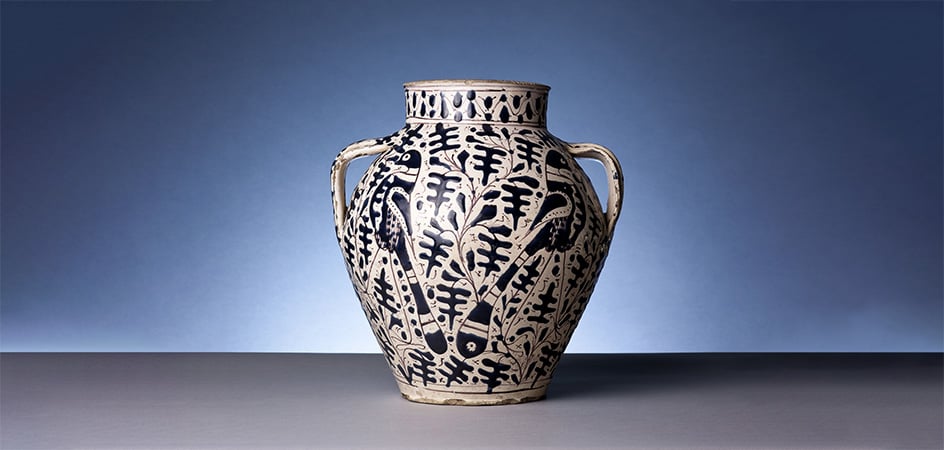

In his painting devoted to Andromeda’s rescue, Piero di Cosimo opts for a distinctly fairy-tale ambiance that softens the myth’s grim aspects. Created between 1510 and 1515 for the wedding chamber of Filippo Strozzi the Younger and Clarice de’ Medici (today at the Uffizi), it portrays the three key moments of the story: at the top right, Perseus flies toward Andromeda to save her from the monster in the center of the scene; immediately afterward, we see him astride the beast, ready to deliver the fatal blow; finally, at bottom right, he restores the maiden – who later becomes his wife – to her family, to everyone’s delight. Eastern-inspired costumes, improbable musical instruments, and curious proportions have made this painting, and its author – known for his flair and originality – quite famous.

Apollo and Daphne: a fateful desire

By contrast, an unrequited love and a rapacious desire is what binds the nymph Daphne – very much against her will – to Apollo. Returning victorious from his battle against the monster Python, Apollo encounters Cupid and, puffed up with pride over his recent triumph, mocks the little god, declaring him too weak to wield bow and arrows, Apollo’s favored weapons. Cupid does not take long to retaliate: he strikes Apollo with a golden arrow, instantly sparking infatuation, and hits Daphne with a lead arrow, causing her to reject love. The sun god falls for the maiden at once, but she flees in a desperate race. Just as Apollo is about to catch her, Daphne cries out for help from her father, the river god Peneus, who transforms her into a laurel tree – a plant from that moment on sacred to Apollo.

Apollo e Daphne by Gian Lorenzo Bernini

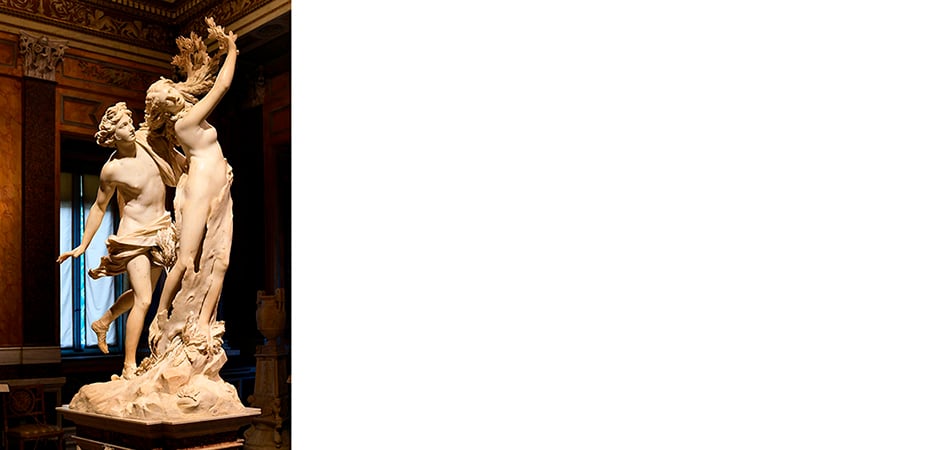

This is the moment Gian Lorenzo Bernini chose to capture in marble. A celebrated artist and architect of early 17th century Rome, Bernini created the work between 1622 and 1625 (Rome, Galleria Borghese). It depicts Apollo chasing Daphne: his left arm is extended, fingers almost brushing her side, but the nymph is already turning to wood beneath his touch. Her skin is becoming bark, her feet becoming roots, her hair becoming leaves. In this astonishing sculpture, we witness in real time the woman still in mid-motion, yet simultaneously rooted to the earth and stretching skyward, changing form. The god’s shock is evident in his gaze and facial expression.

Bernini breathes life into myth, combining dramatic emphasis and compositional balance in an incredibly theatrical, absorbing masterpiece.

Venere, Vulcan and Mars: a love triangle

Venus is famed for her origin story (told in various versions) and her sensual beauty, celebrated in timeless works such as Nascita di Venere by Botticelli (ca. 1485, Florence, Uffizi) or Venere di Urbino by Tiziano (1538, Florence, Uffizi). Yet another episode has also sparked artists’ imaginations: the adulterous affair between the goddess and Mars, the god of War. When Vulcan – god of fire, the Olympian blacksmith, and Venus’s husband – learns of the betrayal from Apollo, he sets a humiliating trap. He lays an invisible net over the bed, waits for the lovers to lie down, and ensnares them before calling all the other gods to gather, exposing the couple to public ridicule.

Are you interested in articles like this?

Sign up for the newsletter to receive updates and insights from BeCulture!

Venere, Vulcano e Marte by Tintoretto

Venere, Vulcano e Marte by Tintoretto (1545–1550, Munich, Alte Pinakothek) is an intriguing work that mixes myth and irony, transforming the classic theme of divine adultery into a near-theatrical scene. Venus lies naked on a dark cloth, her expression uneasy but more from embarrassment than shame. Vulcan, depicted as a mature, bearded man, approaches her with curiosity, trying to uncover her while she clings to the sheet in a gesture of modest refusal. Mars, meanwhile, appears in a comical pose: the war god peeks out from beneath a chest. Trying to escape, he’s betrayed by the barking of a small dog – symbol of marital fidelity. Cupid, a winged child with his arrow, lies asleep just behind them.

Tintoretto thus reimagines the mythological episode as a vibrant, almost farcical scene, rich in symbols and partially elusive meanings. One unresolved detail, for instance, is the exact nature of the mirror (or is it Mars’s shield?) in the background. It doesn’t reflect what’s happening, but rather a later moment when Vulcan is fully on the bed with both legs. Using a device similar to Bronzino’s approach for his Nano Morgante (ca. 1553, Florence, Palazzo Pitti), Tintoretto appears to introduce a time element into his painting – further evidence, in his view, of painting’s superiority over sculpture, which cannot achieve the same effect.

Different as they may be, all these masterpieces reaffirm – if ever there was any doubt – the indomitable power of myth, which, despite the passage of time and social upheavals, still holds its profound imaginative and seductive force. A power forever woven into the history of art and humankind.