If there is a period in the history of Western art characterized by a profound and widespread revitalization of the arts, it is certainly the 15th century. During this century, we witnessed an intense succession of both technical and formal innovations, based on a new ideological framework, then uniquely interpreted in different European areas. One of the most prolific is Flanders, which from the 15th century onwards became the cradle of a defined and recognizable style: what is today known as Flemish painting. Let’s explore its salient features and main protagonists.

Flanders and the “other” Renaissance

In the 15th century, Flanders occupied a territory overlooking the North Sea, nestled between France and the Holy Roman Empire, corresponding to today’s Netherlands and Belgium. In this area, developed around the Duchy of Burgundy – later annexed by France – numerous urban centers like Bruges, Brussels, Ghent, and Antwerp were densely populated and traversed by travelers and goods from all over. A lively social and cultural reality, animated by the ducal court and a wealthy mercantile class eager to assert itself.

In this context, within a few years, artists moved away from the stylistic features of the International Gothic to give life to a new form of painting. The artistic movement, inaugurated by artists like Jan Van Eyck and his brother Hubert, enjoyed immediate and great success, rapidly influencing even the “southern” painting, Italy first and foremost.

The scope of this innovation, which began in the 15th century, is such that some historians explicitly speak of a Flemish Renaissance.

The precursors of flemish painting

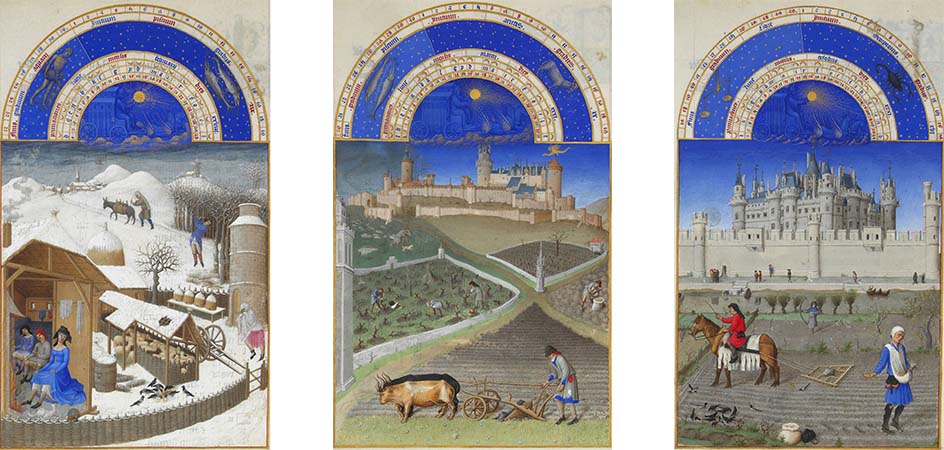

The origins of Flemish painting can be traced back to illuminated manuscripts in which, at the beginning of the 15th century, a new interest in the representation of reality emerged.

This aspect is found especially in the miniatures of the Limbourg brothers. Hired by the Duke of Berry between 1411 and 1416 (the year of their death), they decorated the codex Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (Chantilly, Musée Condé), later finished by other illuminators. Besides psalms and prayers, the codex contains a calendar divided into twelve full-page sheets, each dedicated to a month. Against the backdrop of the Château de Berry, depicted in minute detail, unfold scenes of courtly and peasant life, all sharing a surprising naturalism for both the time and the medium. In the February page, for example, streets and fields are snow-covered, and the trees are bare: on the right, a person blows on their hands to warm them; higher up, a woodcutter leaves fresh footprints in the snow. Inside, a woman lifts her skirt to warm herself by the fire, and just behind, a couple of peasants do the same, of whom we even see their genitals. This is considered the first nude representation in flemish culture, excluding Adam and Eve and grotesque subjects. In October and March, the landscape changes, and with it, lights and shadows: like real objects, the miniaturized characters and animals have visible shadows – lighter and softer in autumn, thicker and darker in spring.

Characteristics and authors

In the same years, Italian painters also became passionate about naturalistic themes but, as always, with different methods and results. Aided by the rediscovery of classical art and Brunelleschi’s theories, Italian artists, from Masaccio onwards, constructed their works according to the new mathematical rules of linear perspective.

Flemish miniaturists and artists, on the other hand, resorted to sophisticated light effects and an increasingly detailed and humanized, almost anecdotal, representation. Reality is rendered with extreme meticulousness: surfaces and materials of any kind are perfectly depicted, detail after detail. A difference that Ernst H. Gombrich in his The Story of Arteffectively summarizes: “[…] it is not far from the truth to say that any work that excels in the representation of the external beauty of objects, flowers, jewels, or fabrics will be by a northern artist, and most likely an artist from the Netherlands; while a painting with bold outlines, clear perspective, and assured knowledge of the marvelous human body will be Italian”.

Fortunately, the two schools did not remain isolated for long; on the contrary, there were fruitful reciprocal influences.

Jan Van Eyck and the revolution of northern painting

Considered the initiator of Flemish painting, Jan Van Eyck has an undisputed influence on the technical, stylistic, and figurative levels. In the service of Duke Filippo il Buono, but also active in the area corresponding to present-day Belgium, he developed a true revolution that would affect artistic production for centuries to come. Vasari had already identified him, erroneously, as the inventor of oil painting – a technique in which, in fact, Van Eyck excelled. Unlike the egg used in tempera painting, oil has longer drying times and allows for a slower and more precise application, with truly astonishing results and color effects.

Thus, in his paintings, details multiply, and light gives objects and people a real consistency; even in the absence of rigorous perspective construction, spaces are not lacking in depth.

The Ghent Altarpiece (or Adoration of the mystic Lamb, 1426–1432, Ghent, St. Bavo’s Cathedral), created together with his brother Hubert, is one of the most exemplary works of this approach. The sober Annunciation of the outer panels contrasts with the majestic Adoration of the Lamb inside. But it is in the lateral figures of Adam and Eve that we glimpse an entirely new realism – so new and concrete that in the 19th century, they were replaced by two clothed copies. Nude, the bodies of the progenitors are painted with such fidelity as to suggest real models: the skin color, hair, forms, and movements – Adam even seems about to step out of the frame.

We find a similar meticulous description in the Madonna of Canon van der Paele (1436, Bruges, Groeningemuseum): the first Madonna and Child with Saints and donors not divided into a polyptych. Here too, the light that envelops the scene and the minute details of the garments, objects, and faces create a composition of great naturalness. Observe, for example, the features of the kneeling canon on the right, with his bloated face marked by wrinkles. Despite the excessive tilt of the floor plane, the whole is extremely credible.

The comparison with the contemporary Pala di San Marco by Beato Angelico (1437, Firenze, Museo di San Marco) and the Pala di Santa Lucia dei Magnoli by Domenico Veneziano (1446, Firenze, Galleria degli Uffizi) highlights the achievements of Van Eyck during these years.

We can say that portraiture is the genre in which Van Eyck’s talent is best expressed. In addition to the famous Man with a Turban (1433, London, National Gallery), probably a self-portrait, the renowned Portrait of the Arnolfini Couple (1434, London, National Gallery) is the perfect synthesis of Van Eyck’s virtuosity. Like an open window onto the lives of the two protagonists, the painting reveals the interior of a wealthy house of the time, with objects of strong symbolic value all around the couple, united in the act of marriage, their faces characterized and expressive. The result is an image with an almost photographic quality, where the real and introspective dimensions meet.

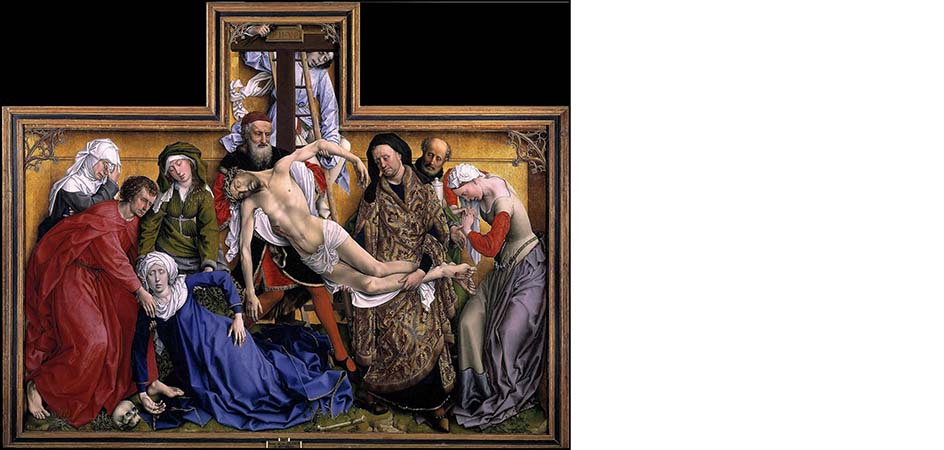

Rogier van der Weyden: the theatricality of sacred art

French by origin (born Roger de la Pasture, later translated into Flemish), Rogier van der Weyden entered the court of Filippo il Buono after Van Eyck. Also prolific and successful, compared to his predecessor, he preferred a more theatrical composition, but certainly no less accurate. Among his masterpieces is the Descent from the Cross (circa 1435, Madrid, Museo del Prado), where Van Eyck’s teachings meet the staging typical of medieval art. The focal point of the representation is Christ, taken down from the cross by a group of Saints. The background is gold, and the cross is partially visible; the composition unfolds horizontally. The pose of Jesus’s lifeless body echoes that of the fainted Vergine, barely supported by Maria Maddalena and San Giovanni. The other characters are immortalized in composed expressions of pain and sorrow – a contrast that contributes to the tragedy of the moment and brings its protagonists strongly to the fore.

We do not have much information about Van der Weyden, but we know that between 1449 and 1450, he visited Italy, stopping in Roma, Firenze, and Ferrara. His contacts with Italian art are evident in some works, especially in his Lamentation and Burial of Christ (circa 1450, Firenze, Galleria degli Uffizi), which, while re-proposing the construction of Fra Angelico’s Pietà (1438–1440, Munich, Alte Pinakothek), simultaneously demonstrates the distance between the two naturalisms. On one hand, the essential and perfectly balanced representation of Fra Angelico; on the other, the crowded and exhaustive vision of Van der Weyden, precise down to the smallest details.

Hugo van der Goes: veracity and symbolism

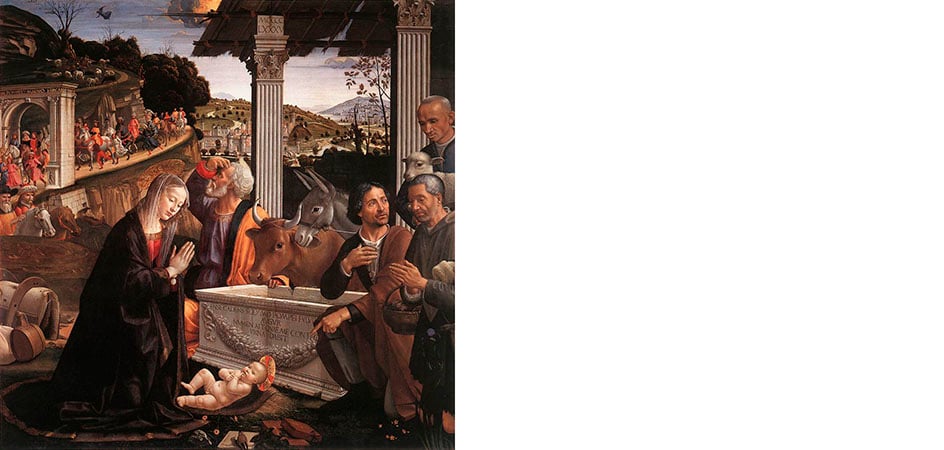

If among Van der Weyden’s works we recognize elements coming from Italian art, the opposite happens with the arrival in Firenze of the imposing Portinari Trittico (1477–1478, Firenze, Galleria degli Uffizi) by Hugo van der Goes, which inspired artists such as Botticelli, Piero di Cosimo, Leonardo da Vinci, and Domenico del Ghirlandaio, who even explicitly pays homage to it in his Adorazione dei pastori (1485, Firenze, Santa Trinita).

The monumental panel (almost three meters high and over six meters long!) takes its name from its commissioner, Tommaso Portinari, banker of the Medici in Bruges, who had ordered it for the family chapel in the church of Sant’Egidio in Firenze. The triptych, after a long journey by sea to Pisa, passing through Sicily, arrived in the city in 1483.

The work masterfully summarizes the achievements of Flemish art and Van der Goes. The three panels feature, on the front, the depiction of the dell’Adorazione dei pastori con angeli e i santi Tommaso, Antonio abate, Margherita, Maria Maddalena e la famiglia Portinari, and on the back, the Annunciazione. The latter, represented in monochrome, elevates the illusion of reality: it is painting simulating sculpture simulating reality.

The central inner panel presents the Adorazione: at the center, the Madonna kneeling before the Child, surrounded by Saints, common people, and angels on the ground and in flight. At the top right, a group of three shepherds – portrayed in all their frank roughness – embody a feeling of human and sincere devotion.

The different sizes of the figures, some decidedly smaller than others, are not linked, as one might think, to prospective reasons but to an ancient hierarchical convention. A feature that, in the eyes of his contemporaries, did not undermine the truthfulness of the work; on the contrary, it reaches its peak in the extraordinary still life in the foreground. The double vase of flowers advanced against the background of a sheaf of wheat is rich in allegorical meanings: purity and the blood of Christ’s Passion are recalled by the white iris and the red lily; the purple columbine anticipates the Virgin’s sorrow; the carnation alludes to the Trinity; while the wheat recalls the bread broken at the Ultima Cena.

The landscape in the background – animated by small rural scenes – visually connects the three panels, giving a sense of continuity and unity to the work. In the side panels, at the margins of the main subject, appear the kneeling members of the Portinari family: on the left, the father with his two sons, Antonio and Pigello, along with Saints Tommaso and Antonio Abate; on the right, his wife Margherita with their daughter Maddalena and the homonymous patron Saints.

From the clothes to the details of nature, everything testifies to the great precision and ability of the artist to reproduce reality.

Although highly esteemed and influential, Van der Goes had a short career: at the age of forty, struck by great melancholy, he retired to Brussels to live in a convent, dying shortly after.

Are you interested in articles like this?

Sign up for the newsletter to receive updates and insights from BeCulture!

The flemish painters at the Galleria degli Uffizi

Knowing the history of art, besides being enjoyable, guides us in interpreting artworks and understanding contexts and meanings, although experiencing them in person is always recommended. It may surprise you to know that one of the most important collections of Flemish painting in Europe is preserved in Italy, at the Galleria degli Uffizi. The rooms, recently renovated and dedicated to Flanders, the Netherlands, and Germany, host the aforementioned masterpiece by Van der Weyden but also paintings by Dürer, Cranach, Memling, Froment, and other artists from beyond the Alps, collected by the Medici, great patrons.

Three spaces where Northern and Italian painting dialogue in an exchange of intuitions, experiments, and mutual influences.A unique collection that deserves a visit!