Home / Experience / Michelangelo Buonarroti

Michelangelo Buonarroti

Painter, sculptor, architect and poet, Michelangelo left us a legacy of extraordinary works. Born in 1475 in Caprese, a small village near Arezzo, he showed such exceptional talent from an early age that he was already considered a genius by his contemporaries.

His early years and the birth of the legend

His father Ludovico Buonarroti, from a noble but fallen family, was the mayor of Caprese and administered the territory on behalf of the Medici family. Realising his son’s precocious talent, he decided to send the young Michelangelo to the workshop of Domenico del Ghirlandaio, around 1487.

During those formative years, Michelangelo was able to admire the vast collection of antique marbles belonging to the Medici family, a historic family of bankers who had by then taken over the leadership of the city, at the Giardino di San Marco, and it was here that he became passionate about studying classical art: a fundamental step in his training.

Despite his undeniable talent, it is curious that his beginnings are linked to an episode of forgery. Around 1496, Michelangelo sculpted a statue of a sleeping Cupid on commission from Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici. The plan was to sell it to Cardinal Raffaele Riario, passing it off as an antique original. We do not know whether the idea of burying the cupid to accelerate its ageing was Michelangelo’s, Lorenzo’s or that of his art dealer Baldassarre del Milanese, but what is certain is that the prelate was no dunce, and soon discovered the deception, demanding compensation. Despite this, the cardinal did not overlook the undoubted talent of the young sculptor, so much so that he commissioned him to paint Bacchus (1496–97) now in the Bargello National Museum. Michelangelo’s value had been acknowledged.

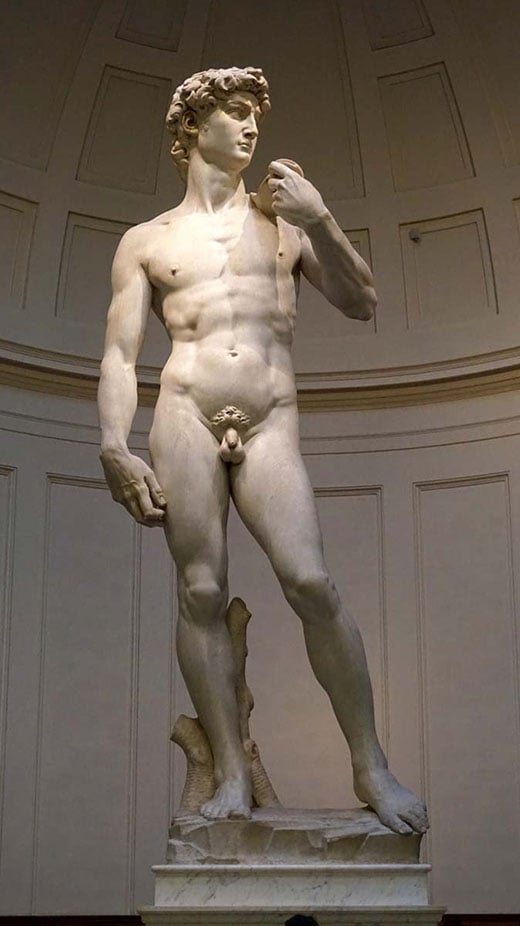

The David

It was 1501 when Michelangelo began work on the enormous block of marble, commissioned by the Arte della Lana and the Opera del Duomo of Florence. Two artists, Agostino di Duccio and Rossellino, had already sketched it out and given up because of the difficult quality of the marble. This obstacle did not prevent the young Michelangelo from creating one of the most sensational sculptures in the history of art: the David. Immediately recognised as a masterpiece, the authorities set up a commission of experts, including Leonardo, Botticelli and Perugino, to decide on its location, which was finally chosen at the entrance to Palazzo Vecchio. Facing the centre of urban power and in the heart of Florence, the figure of the young biblical hero with the resolute gaze was to become the symbol of the city.

The majestic figure of David, a reflection of the pride and freedom of the Florentine Republic, represents an epochal turning point in the history of art: unlike the sculptors who preceded him, Michelangelo depicted the biblical hero without a sword, armed only with a sling, while he lets the observer guess the presence of Goliath off the scene. David is not yet the victor, he is waiting. Everything, from the pose to the gaze, reveals his psychological preparation for battle.

The Roman years and the Sistine Chapel

Around 1505, Michelangelo was called to Rome by Pope Julius II della Rovere. This was the beginning of a fruitful but also complex relationship given to the irascibility and intransigence of both their characters.

It was Julius II himself who commissioned him to paint the frescoes of the entire vault of the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican. It was Michelangelo’s first opportunity to try his hand at fresco technique, and although he considered himself a sculptor and not a painter, he accepted the ambitious commission in 1508. It would take four and a half years of hard work, vain attempts, changes of direction and huge sums spent for materials, equipment and personnel to succeed in completing the work, but Michelangelo once again exceeded all expectations and left the world a spectacular work that was destined to shape the fate of Western art.

The undertaking of the Sistine Chapel had forced Michelangelo to interrupt another work of immense proportions: the funeral monument for the pope commissioned in 1505. Only in 1520, paradoxically after the pontiff’s death, did he begin the sculptural cycle of the Prisoners, conceived to decorate his tomb. The original design of the imposing marble tomb merged architecture and sculpture into one majestic work to be placed in St Peter’s Basilica. Visible 360°, it envisaged some forty statues. The Prisoners in particular, with their symbolic character, were conceived as decoration for the base of the colossal tomb. According to some sources, these subjects represented the provinces subjugated by the Pope, or the Arts, reduced to chains by the death of a great patron.

Michelangelo did not finish any of the monument’s works, but left us four splendid unfinished works, the sketched sculptures of the Prisoners, which may be seen today in the Galleria dell’Accademia in Florence, and which reveal the majesty of the project.

The tomb would see the light of day almost thirty years after the death of Julius II, albeit drastically reduced, and is today in the Church of San Pietro in Vincoli in Rome, where the imposing sculpture of Moses (1513–15) stands out.

Michelangelo as an architect in Rome and Florence, the Medici Chapels

Ever interested in architecture and its potential, the first commissions came only in 1518 and in his hometown Florence; first with a project for the façade of San Lorenzo which was never undertaken, then concretely with the commission of Cardinal Giulio de’ Medici to create both the New Sacristy in the Medici Chapels – part in the church of San Lorenzo – and the Laurentian Library. Of the two works, the first is undoubtedly the more famous. Intended to contain the funerary monuments of Giuliano, Duke of Nemours and Lorenzo, Duke of Urbino, work on the new chapel began around 1520, two years after the failed attempt to give the church a façade. For the New Sacristy he therefore created an architectural system inspired by Brunelleschi, with exemplary geometries, light and slender upward movements, where the wonderful sculptures of the Allegories of Time fit perfectly: Dawn, Day, Dusk, and Night, created between 1524 and 1531, along with the statues of the two young Medici.

Having concluded his Florentine experience, in 1534 he began to design the new system for Piazza del Campidoglio, commissioned by Pope Paul III to prepare Rome for the visit of Emperor Charles V.

The square already had two buildings, the Palazzo Senatorio and that of the Conservatories. Michelangelo followed the renovation and designed a third palazzo, later known as Palazzo Nuovo, so as to create a trapezoid that points towards St. Peter’s, the centre of papal power. The works for this splendid urban renewal ended in 1538 and Michelangelo’s hand is still clearly visible today in the historic square.

Art is Life

Michelangelo’s works immediately stand out for their extraordinary modernity, the capacity and expressive originality that shifts the parameters of interpretation every time.

In the Vatican Pietà, created when he was not yet twenty-five, the face of Mary and the body of Christ radiate bliss; grace and piety are the key feelings, not suffering and torment as in the common representation.

The devotion to his work was total; he was present at every stage. Michelangelo would go in person to the quarries throughout his life, on the back of a mule, to choose the marble for each of his works, the characteristics and purity of which he would instinctively recognise. Like when in 1517 for the construction of the façade of the Church of San Lorenzo, almost on the summit of Monte Altissimo in the Apuan Alps, he identified a vein of marble which he defined as “united in grain, homogeneous, crystalline” and which was “reminiscent of sugar.”

He was so dedicated to his art that he had no interest in worldly things, as the younger Raffaello Sanzio was known to do. The two great artists probably met during the young Urbinite’s stay in Florence between 1504 and 1508, but it was in Rome, both as guests of the papal court, that their lives actually began to intertwine. Also considered by their colleagues as the two finest in the field, two opposing camps began to form around them, both with the aim of stealing commissions and praise from the other. Providing preparatory sketches, Michelangelo began to help his friend Sebastiano del Piombo, another famous artist working in Rome at the time, to create better works and in a shorter time than those of Raphael. On the other hand, Bramante would not hesitate to use his great influence at court to favour Sanzio, a friend and fellow countryman.

Despite these minor feuds and major character differences, both had clear respect for each other’s work. The younger Raphael studied the works of his Tuscan rival in depth, and demonstrated that he deeply understood his soul. In the wonderful fresco The School of Athens (1509–11) in the Vatican Rooms, the artist from Urbino depicts all those he considers the great masters of the time, including Leonardo in the guise of Plato and Bramante as Archimedes, and he also includes Michelangelo in the role of Heraclitus. Not only does he identify his rival as one of the greatest Athenian philosophers, thus acknowledging his greatness, but he depicts him in a meditative state, aloof, frowning and contemplating, showing how much Raphael was able to understand Buonarroti’s character.

In fact, the great artist had few but very dear friends, and lived a frugal life. Many at the time believed him to be on the verge of poverty. In actual fact, Michelangelo had amassed an immense fortune in real estate and gold ducats, which were only found after his death. From his letters to his father Ludovico we know that the artist supported practically the entire family financially. The Buonarroti, as already mentioned, were a family of ancient nobility but neither the father nor his uncle Francesco had been able to manage the family heritage well. Michelangelo, who had become a genuine celebrity, regularly sent money to his father and brothers, which often caused arguments. Despite accepting and seeking his son’s riches, his father had little patience for his profession as an artist, which he considered unworthy of a city nobleman. In one case, the two even end up in court, perhaps due to the growing demands of his family. In 1523, in one of these letters, Michelangelo wrote:

“If my existence bothers you, you must have found a way to provide for yourself, and you will redeem that key to the treasure that you say I have. And rightly so, for it is known throughout Florence that you were a great prince and that I always stole from you, and deserved punishment: you will be greatly praised! Shout and say what you want about me, but do not write to me anymore, for you distract me from my work: I still have to make up for what you have taken from me over the last twenty-five years.”

From this perspective we can better understand the relationship that the artist has with money. Perhaps his obsession with saving stems precisely from the awareness that the fate of his entire family depended on his own fortune, not to mention the childhood marred by the trauma of economic hardship due to his father’s financial mismanagement.

Painting and the Tondo Doni

Even in painting, Michelangelo managed to break with the conventions of his time and introduce new points of view. The Tondo Doni (1505–06), today in the Uffizi collection, is an example of this due to its extraordinary characteristics: Mary is sitting on the ground, like a common woman, while her body is depicted twisting, caught in the act of taking her son in her arms. The subjects of his paintings are solid, vigorous, characterised by a strong chiaroscuro and the use of bright colours.

The anatomical forcing and tensions, as well as the intense use of colour, would be taken up by the artists of the next generation, the so-called mannerists. The strength of Michelangelo’s bodies, the divine grace of Raphael’s works and the mysterious languor of Leonardo would be the inspiration for the so-called Serpentinata figure, that is, sensual and wrapped around itself, which we will find in the works of painters such as Bronzino or in the sculptures of Giambologna.

Michelangelo poet

A fact less known to the general public is Michelangelo’s passion for literature and in particular for poetry. A great connoisseur and admirer of the works of Dante, Petrarch but also Lorenzo de’ Medici and Agnolo Poliziano, Buonarroti’s soul often found expression in rhyme. Indeed, the collection of more than three hundred of the artist’s compositions published posthumously by his nephew is entitled Rime. A very precious tool for the interpretation of his life and work, they reveal a grumpy and suffering soul, an abysmal sense of loneliness despite his fame.

The Rondanini Pietà

At the age of 89, Michelangelo was still working on the Rondanini Pietà, which although unfinished is still striking in terms of its great expressive power. The ardour that permeates all of his work did not abandon him even a few days prior to his death, which took place in Rome on a rainy 18 February 1564.

According to the testimony of his friend and confidant Daniele da Volterra, “He worked all Saturday, which was before the Monday that he fell ill; he worked all Saturday on Carnival Sunday, and he worked standing up, over that body of the Pietà.”

His nephew Leonardo organised the return of his body to Florence, but the Roman authorities opposed him: they had no intention of letting go of the remains of such a genius. Thus the Florentine faction, having stolen the body, then transferred it to their hometown under the cover of night, placing it in the church of Santa Croce where it has remained ever since.

Michelangelo’s death marked the end of an era, the end of a formidable artistic crescendo that elevated the souls of his contemporaries. His influence, his memory, lives on and continues to amaze the world.

Cover photo: Michelangelo Buonarroti, circa 1545, Daniele da Volterra, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA

Caprese 1475 – Rome 1564

Painting, sculpture, architecture and poetry

Giardino di Boboli

Purchase ticketGli Uffizi

Purchase ticketPalazzo Pitti

Purchase ticketMuseo Nazionale del Bargello

Purchase ticketRelated products

Related museums

From €16,00

Originally the residence of the wealthy Florentine banker Luca Pitti, this magnificent palace was purchased in 1550 by Grand Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici, who established his court there with his wife Eleonora of Toledo. After two centuries, from 1737, the palace was to be the residence of the Lorraine family, who succeeded the Medici in the Grand Duchy, and later of the Savoy family during the five years when Florence was the capital of Italy.

Average visit time:

2 hours