Home / Experience / Mannerism

Mannerism

At the decline of the Renaissance, Italian art and literature underwent a significant transformation, gradually losing many of the formal and chromatic qualities typical of the 15th century and early 16th century. This shift paved the way for the emergence of the Baroque.

Whereas Renaissance culture was born and spread from a single city—Florence—Mannerism began to take shape and diversify within the individual courts of Italy. Many artists trained in Florence at the end of the 15th century began, in the early 1500s, to move to Rome, under the patronage of papal figures such as Julius II and Leo X. The workshops founded in the papal capital by masters like Raffaello and Michelangelo, along with the influence of their works, were of fundamental importance for the generations that followed.

The “Great Manner”: origins and meaning of the term Mannerism

To understand the origin of the term Mannerism, we must go back to 18th-century art criticism, influenced by the Vasari’s Vite. According to this view, Leonardo, Michelangelo and Raffaello had achieved an unsurpassable artistic perfection. Their style was known as la “la Grande Maniera” (where Maniera means, indeed, style).

The art of the 16th century was thus seen as an attempt to imitate that perfection—but with lesser results. The word Mannerism was therefore originally meant as a pejorative, marking an era of artistic decline.

This definition retained its negative connotation for a long time. Today, however, art historians consider Mannerism to be a period of further renewal, which laid the groundwork for the Baroque and has its own value and achievements.

Praised by the avant-gardes of the 20th century, Mannerist art—although partially inspired by the three great masters of the High Renaissance—introduced great innovation and distinct characteristics.

The sack of Rome and the artistic diaspora

For the first time since the barbarian invasions of the 5th century that led to the fall of the Roman Empire in Italy, Rome was besieged in 1527. For days, the Landsknechts hired by Charles V, Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, savagely looted the city.

The Sack of Rome had major consequences. It occurred during the papacy of Clement VII, a pope from the Medici family who had gathered around him many of the artists later defined as Mannerists. In the wake of the battle, most of them left the city, settling in the courts of central and northern Italy. Among them were Benvenuto Cellini, Giulio Romano, Sebastiano del Piombo, and Parmigianino.

While this may be the most striking cause of the spread of Mannerism, it does not mark its origin. The first signs of this artistic and cultural shift actually date back around a decade earlier, once again in Florence. Around 1515, artists such as Pontormo, Rosso Fiorentino, and Andrea del Sarto began to break away from the classical conventions of the Renaissance. They were restless personalities, expressing inner turmoil in their works—also influenced by Michelangelo’s recent masterpiece, the Sistine Chapel. It was Rosso Fiorentino himself who moved to Rome in 1523, bringing with him this innovative desire to break with tradition and to measure himself against the great masters of the recent past.

The art of Mannerism: works and characteristics

In Mannerist painting, artists often embedded hidden meanings, enigmas, cultural puzzles, decipherable only by the most educated viewers. The literature of the time was similarly complex—a stylistic exercise for the few. This refinement and elitist character appealed greatly to the ruling classes, and the European courts welcomed artists fleeing Rome with open arms. This new generation of intellectuals, painters, sculptors and writers began speaking to a very select group of cultured and wealthy patrons who sought works for themselves, rather than to exalt the glory of their city.

Motifs and typical features

A hallmark of Mannerist art is the use of the figura serpentinata—human figures depicted in extreme, often unnatural twists, conveying tension and unease. The colour palette, on the other hand, with its vivid and brilliant tones, appears to be a direct inheritance from the Sistine Chapel ceiling.

Mannerist artists no longer sought to imitate nature or rationality. Figures are often elongated and sinuous, the subjects cold yet intensely sensual. Art becomes a display of virtuosity—sophisticated, refined, and difficult to interpret.

Mannerism in painting

On the one hand, we see the courtly, meticulous and graceful style of Bronzino —student of Pontormo and official portraitist of Cosimo I de’ Medici, on the other, we find works that increasingly reject the classical models of their predecessors.

Art now aims to amaze, provoke and unsettle. It is no coincidence that this period saw the creation of paintings, frescoes and sculptures focused on the grotesque and on illusionistic perspective.

Entire rooms were painted from floor to ceiling with imaginary landscapes and architectural fantasies. A striking example of this decorative approach is the magnificent fresco cycle at Palazzo Te in Mantua, created by Giulio Romano, one of Raphael’s most famous pupils.

Built and decorated over roughly a decade (1525–1535), Palazzo Te embodies the principles of Mannerist architecture. Though partially altered in later centuries, it still preserves much of the invention and intention behind its creation: a villa designed for the leisure of Prince Federico II Gonzaga (later Duke of Mantua) and the reception of his guests.

Mannerist sculpture

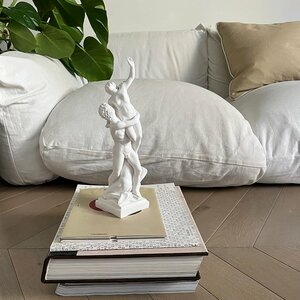

In sculpture, the approach was similar: many works were conceived as displays of skill.

Giambologna’s famous Ratto delle Sabine (1582) is a continuous spiral of bodies, full of violence and eroticism. Cellini’s Perseo con la testa di Medusa (1545–1554), on the other hand, demonstrates extreme attention to detail—even in the tiniest elements.

Both sculptures remain in their original locations at the Loggia dei Lanzi in Florence, while the Ratto delle Sabine terracotta model is housed at the Galleria dell’Accademia.

The grotesque as a tool to astonish

One legacy of this period is the fascination with the comical, the unexpected. The goal is always the same: to astonish. Agnolo Bronzino’s Nano Morgante (before 1553), now at Palazzo Pitti, is one of the most significant works in this regard. The canvas is painted on both sides, portraying the court dwarf nude from both the front and the back.

With this curious work, Bronzino sought to demonstrate the superiority of painting over sculpture—capable of rendering not only three-dimensionality but also the passage of time.

In addition to its excellent technical execution, the double-sided portrait is striking for its eccentricity, foreshadowing the taste for the unusual and extravagant that would flourish in the Baroque era.

Photo: Double portrait of the Dwarf Morgante, 1552, Agnolo Bronzino

Related products

Related museums

From €16,00

Originally the residence of the wealthy Florentine banker Luca Pitti, this magnificent palace was purchased in 1550 by Grand Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici, who established his court there with his wife Eleonora of Toledo. After two centuries, from 1737, the palace was to be the residence of the Lorraine family, who succeeded the Medici in the Grand Duchy, and later of the Savoy family during the five years when Florence was the capital of Italy.

Average visit time:

2 hours