A wooden board, originally shaped and designed to serve as a shield and covered with canvas, is circular yet imperfectly so, and has a curved profile. Interestingly, it had been pre-painted on its concave side by an unknown artist. It seems to be a mark of true genius, the capacity of great artists to create unparalleled works from materials that have already been manipulated. An exemplar of this is Michelangelo who carved his renowned David from a challenging block of marble that had been cast aside by two other sculptors. Following in similar footsteps, another master named Michelangelo – Michelangelo Merisi, known as Caravaggio (1571-1610) – transformed a simple wooden board into what is considered one of the greatest masterpieces of all time.

His Testa di Medusa, dated around 1598, is still today one of the most admired and studied “pieces” – to use Caravaggio’s word, a term highlighted by art critic Roberto Longhi (“What had prevented anyone before him from faithfully rendering what he called for the first time a “piece” of reality, if not the ancient fabula de lineis et coloribus that he now perceived as a mythology to finally let fall? He looked around himself, and reality appeared to him in “pieces”, frozen chunks of a universe where there was no place for outlines, highlights or colors with abstract formulas […]”) – of the Lombar artist.

A mere glimpse of this work, whether through reproductions or, even better, in person at the Uffizi in Florence, is enough to enthrall any observer. Yet, a deeper examination unfolds the full grandeur of this remarkable piece.

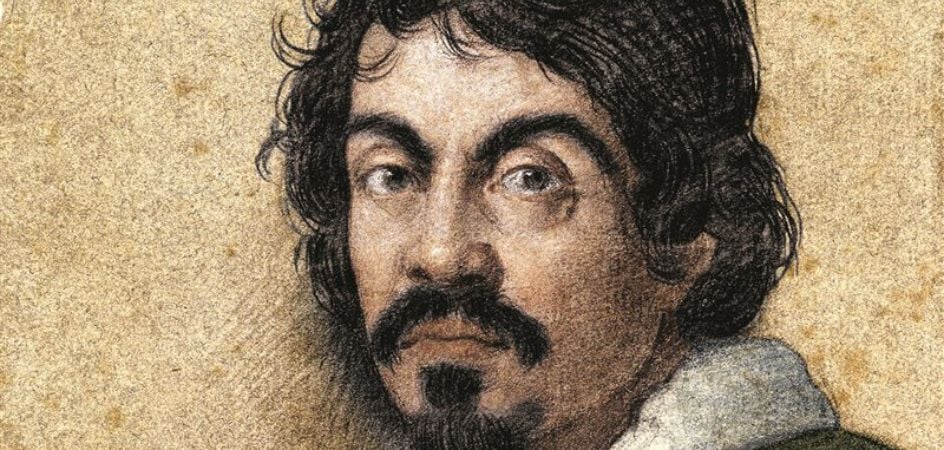

Medusa by Caravaggio

The exact date Caravaggio painted Medusa remains uncertain due to a lack of definitive sources. It is known, however, that Cardinal Francesco Maria Del Monte presented the artwork to the Galleria degli Uffizi as a gift for Ferdinando I de’ Medici, the Grand Duke of Tuscany.

The likely date of delivery is September 7, 1598, as suggested by an entry in the Medici wardrobe inventory. One can envision the Grand Duke’s surprise as he unwrapped the shield from its tanè velvet cover, revealing Medusa‘s terrifying gaze, her mouth agape, the snakes entwined in her hair, her severed neck, and the vivid streams of blood, all set against a darkly shaded green backdrop.

Caravaggio’s revolutionary approach to painting, especially his manipulation of light, is unmistakable. The light, originating from a high, indeterminate point to the left, bathes the subject, crafting an astounding illusion where the shield’s convex surface appears concave from certain perspectives.

Each element – the petrified expression, the serpentine hair – resonates with stunning realism.

The scene is a captured moment in time: Medusa has been decapitated, yet the painting pulses with life. Her eyes seem to follow the viewer, and the snakes – depicted with scientific accuracy as real vipers – seem to be actively avoiding her deadly gaze. These details may have been observed firsthand by Caravaggio, possibly at Cardinal Del Monte’s residence, known for his interests in science and nature, which may explain the presence of such reptiles.

The painting continues to evoke surprise today, much as it did upon its unveiling. It inspired poetic tributes from Gaspare Murtola and the more renowned Giovan Battista Marino. Despite missing the leather straps and back padding and being presented differently from the original Persian armor given by King Abbas the Great of Persia to the Grand Duke Ferdinando de Medici, Medusa remains a source of fascination.

What prompted the commissioning of this theme to Merisi, and what deeper meaning does it hold?

The origin of Medusa: the myth of Perseus

The myth of Perseus and Medusa, which has varied in its telling by classical authors like Ovidio, Lucano, and Plinio, was also familiar during Caravaggio’s era. Here, we briefly summarize this myth to shed light on the artwork’s iconography.

Perseus, son of Danae and Zeus, embarked on a quest to slay Medusa and bring back her head, determined to protect his mother from the unwelcome advances of King Polidette. Medusa was indeed the only mortal among the three Gorgon sisters and the most beautiful among them. Punished by Athena for desecrating her temple after coupling with Neptune, she was transformed into a monstrous creature with hair made of snakes and a gaze that turned anyone who crossed it to stone.

With divine assistance from Athena and Hermes, Perseus was guided to the Graiae, the Gorgons’ sisters. By seizing their shared eye and tooth, he gained knowledge of the Nymphs’ location, guardians of magical items including the cap of invisibility from Hades, winged sandals, and a magical pouch. Equipped with Hermes’ unbreakable sickle and under Athena’s guidance, Perseus cleverly used the reflective shield to avoid Medusa’s stony gaze and decapitated her. From the blood that spilled from Medusa’s head sprang Pegasus, the winged horse, and the giant Chrysaor.

Medusa’s head became a powerful weapon used from Perseus to vanquish foes on his homeward journey. In recognition of this deed, the visage of Medusa’s snake-encircled head was immortalized on Athena’s resplendent armor.

Historical precedents and recurring motifs

The subject of Medusa was not new to art history. Much has been discussed and is still debated about the sources that inspired Caravaggio to create this work.

Among the most credible hypotheses is that a painting with the same subject by Leonardo Da Vinci already existed, preserved in the Medici collections. Mentioned by Giorgio Vasari in his Vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori e architettori(1550), the painting is now lost, but it is likely that, if not Caravaggio himself, at least Cardinal Del Monte had admired it during his long stay in Florence. Others even speculate that it was to compete with Medusa by Leonardo, or perhaps to replace it because it had already been lost, that the cardinal commissioned a new one from Caravaggio.

Unfortunately, we have no testimonies of Leonardo’s painting except for Vasari’s words, but it is curious how for a long time this was identified with another panel still present in the Florence pinacoteca and later attributed to a seventeenth-century Flemish school painter.

Whatever the relationship between the two works, it is certain that Caravaggio was not the first to depict Medusa, nor was he the first to enter the Medici heritage. There are many examples of Gorgons over time: from ancient Etruscan urns to monuments of Roman age, to sculptures, sarcophagi, coins, and even to armor – of which the Lombard culture of the Renaissance is particularly rich. One above all: the Rotella del Bargello, a sixteenth-century steel shield preserved at the Museo del Bargello in Florence. Moreover, the panel depicting Minerva by Fra Bartolomeo (datable around 1490-95) in which the face of the Gorgon is impressed on the shield of the goddess, and the Tazza Farnese, a splendid masterpiece of Hellenistic glyptics, already listed among the possessions of Lorenzo il Magnifico. Some researchers suggest that it was this that inspired Caravaggio, who would have seen it in Rome at the end of the sixteenth century when the cameo had already been acquired by Ottavio Farnese as part of the dowry of Margherita of Austria, the widow of Alessandro de’ Medici.

The theme of Medusa was therefore well-known and dear to the Medici, also for its symbolic implications. But Caravaggio knew how to innovate it, re-proposing and anticipating some of the features of his own production. How can we not recognize, in that “stifled scream that lasts a quarter of a second after the beheading” (as described by Roberto Longhi, one of the greatest scholars of Caravaggio) the extreme expression of the Ragazzo morso da un ramarro painted by the artist just a few years earlier? And indeed, Caravaggio’s painting is often synesthetic: to the aforementioned we can add the silent screams of the young man fleeing in The Martirio di san Matteo (1600-1601) at the Cappella Contarelli in San Luigi dei Francesi in Rome and of Isaac in the Sacrificio di Isacco (1604-1604), displayed in the Galleria degli Uffizi.

Nor would this be the only beheading Caravaggio would undertake. Just think of his Giuditta e Oloferne (1599) or the Davide con la testa di Golia, from 1605-1606 and 1607. In all, the successful device of the lifeless face returns: the wide-open mouth, the bared teeth, the bloody neck.

Possible meanings and interpretations

So, what’s Medusa’s meaning?

The meaning behind the Medusa imagery can be interpreted in various ways. There is a consensus that Cardinal Del Monte’s gift represented not just a token of friendly and pragmatic relations – as he handled Medici affairs in Rome – but also a recognition of the Grand Duke’s ultimate wisdom.

Lodovico Dolce’s writing in the early sixteenth-century suggested that presenting an image of Medusa could symbolize a warning against the seductive distractions of the world that “petrify” men, rendering them insensitive and immobilized from performing virtuous acts. Essentially, the image of Medusa was meant to serve as a protective emblem, similar to the one the goddess Minerva – emblematic of wisdom – chose for her armor.

Furthermore, the Medici family had previously infused the myth of Perseus and Medusa with political significance. Cosimo I de’ Medici had commissioned Benvenuto Cellini to craft a bronze statue of Perseus with the head of Medusa, placed in the Piazza della Signoria in Florence, serving both as a deterrent and a celebration of the Medici’s power.

Are you interested in articles like this?

Sign up for the newsletter to receive updates and insights from BeCulture!

3 lesser-known facts about the Medusa by Caravaggio

The Uffizi’s Medusa may not be the sole depiction by Caravaggio of this subject. Maurizio Marini, during his investigation, uncovered another painting with similar characteristics in a collection from Milan, known as Medusa Murtola. He posits that this version, which was in Caravaggio’s possession in the early 1600s, was the piece celebrated by poet Gaspare Murtola.

Despite this, there’s a tendency among some to consider it a replica, an occurrence quite common for that period and particularly with Caravaggio, whose creations often saw numerous non-autograph reproductions.

Regarding the artwork itself, the green backdrop against which Medusa is set is laced with traces of gold, notably used more liberally along the decorative border. This detail hints at Caravaggio’s possible initial attempts at portraying the canvas’s transparency, an idea that might have originated from Del Monte but was eventually abandoned.

Public executions were a common spectacle in the era Caravaggio lived and produced art, and he is believed to have been a witness to many. In particular, it’s thought that he was present for the 1599 execution of Beatrice Cenci, a Roman noblewoman put to death for the alleged murder of her abusive father – a narrative that fueled the imaginations of artists and the superstitions of the populace. Her haunting tale, which purportedly included annual apparitions of her carrying her severed head, has cemented her place in popular lore.

In connection with popular beliefs, it was a common belief at the time to avoid looking into the eyes of the decapitated. The fear was that in their final moments, the executed could capture someone with their gaze, dooming that individual to be the next to die. This belief is mirrored in the verses of Murtola, referencing Caravaggio’s portrayal of Medusa: “Is this from Medusa / The poisoned hair, / Armed with a thousand serpents? / Yes, yes: do you not see how / She turns and twists her eyes? Flee from disdain, and anger / Flee, for if she petrifies your gaze with amazement, / She will also turn you into stone”.

Despite these old beliefs, today the notion of shunning Medusa‘s gaze is peculiar to us, as we often find ourselves fascinated, even delighted, by the very sight we would once have feared.