It’s impossible not to know it: the Nascita di Venere (circa 1485, Florence, Uffizi) is one of the most admired and emblematic works of the Italian Renaissance. Yet, what we know today about Sandro Botticelli‘s masterpiece is very little compared to the fame that accompanies it.

An aura of mystery indeed surrounds the canvas: the date of execution, patronage, and content are still uncertain. Even the title is imprecise.

But none of this diminishes its charm – on the contrary! Let’s retrace the information we have to try to reconstruct its genesis and meaning.

Iconography and possible sources of inspiration

Named as such in the 19th century, the Nascita di Venere does not actually depict the origin of the goddess. According to a widespread version of the myth – as told by Esiodo in the Teogonia – Venere was born, already a woman, from the contact between the sea water and the severed genitals of Urano, the god of the sky.

However, what we see in the Florentine canvas is not an Afrodite Anadyomene, that is, rising from the water, but a Venere sailing toward the mainland, ferried by the shell of a scallop. An attribute of the goddess since antiquity, the shell is present in numerous depictions of her and in various forms: smaller in size, held in hand, or placed near the belly.

The Venere by Botticelli appears nude and unadorned. She covers her pubis with a lock of hair gathered in her left hand, while resting her right on her breast – a pose known as the Pudica, likely familiar to the artist due to his knowledge of classical sculpture.

In the second half of the 14th century, Benvenuto Rambaldi da Imola reported that “in Florence, in a private house, there was a wonderfully beautiful statue of Venere adorned as in ancient times: naked, she held her left hand bent, covering the parts of modesty, and with the other, raised higher, she covered her breast. This statue was said to be the work of Policleto.”

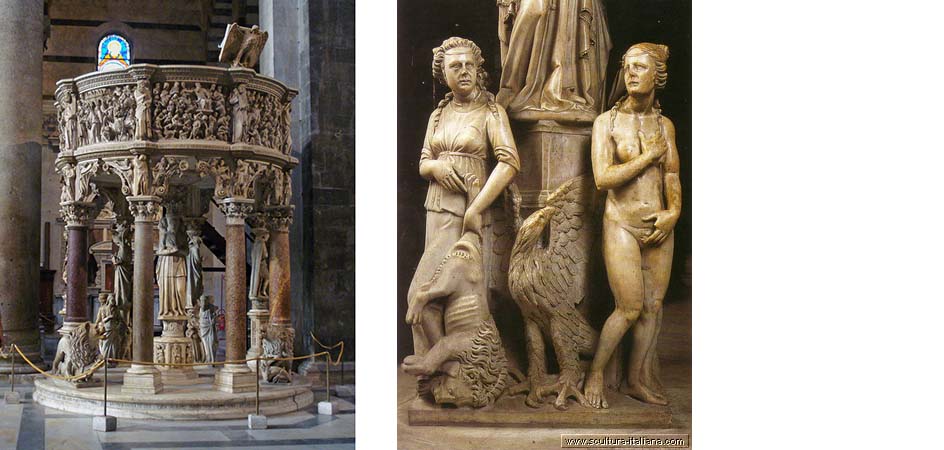

We do not know what happened to this Florentine Venere, but the same pose can be seen in the Venere de’ Medici (late 2nd century BC – early 1st century BC) at the Galleria degli Uffizi and the Venere Capitolina (1st–2nd century AD) at the Musei Capitolini in Rome. It also appears in the Prudenza by Giovanni Pisano on the Pergamo di Pisa (1302–1311) and in the Eva by Masaccio (1425, Florence, Santa Maria del Carmine), confirming its widespread use.

Compared to the others, however, the Venere by Botticelli is even more sinuous. Her body appears strongly inclined to her left: sloping shoulders, an arm extended along her side, and a tilted head accentuate her suppleness. This choice aligns with the prescriptions in De Pictura by Leon Battista Alberti1, who suggested inserting “the face of Zefiro or Austro, who blows within the clouds at one point of the story towards the opposite part.”

This guidance helps identify the male figure at the top left: it could be Zefiro, the wind of Greek mythology that, especially in spring, blows from the west; entwined with him is Aura or perhaps Iris. Another interpretation sees this winged couple as Amore e Psiche, following a recurring theme in the bas-reliefs of Roman sarcophagi.

Even the young woman rushing to offer the flowery mantle to the goddess raises some doubts. Today, she is often recognized as one of the Ora della Primavera. However, among experts, references to one of the Grazie or to Peito are not lacking, commonly described or represented in ancient sources accompanying the newly born Afrodite.

The flowers, particularly myrtle (a symbol of renewal) and roses (born with the goddess), are significant but do not help resolve the question, as they are compatible with all these alternatives.

Behind the maiden, the coastline unfolds to the horizon. The background, dominated by the marine landscape, features a grove of orange trees on the right – a possible reference to the Medici family (oranges were called mala medica, medicinal fruit), among the possible patrons of the work.

Origin and patronage

Today, scholars agree in dating the Nascita di Venere around 1485, after Botticelli’s Roman sojourn and following the creation of the Primavera (1480, Florence, Uffizi), a work to which it is indissolubly linked.

The oldest and most precise description documenting the Nascita di Venere is offered by Vasari, who in 1550 writes in his Vite2: “Throughout the city, in various houses, (Botticelli) made tondi by his own hand, and many nude females; among which today at Castello, villa of Duke Cosimo, there are two paintings depicting, one, Venere who is born, and those auras and winds that make her come to earth with the Amori; and also another Venere, whom the Grazie are flowering, denoting the Primavera; which are seen expressed by him with grace.”

Therefore, in the mid-16th century, Vasari saw both the Venere and the Primavera together at the property of Castello, then property of Cosimo I de’ Medici.

At the time of their creation, however, the villa belonged to Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici (called il Popolano), who in 1477 had purchased it from his more famous and powerful cousin Lorenzo il Magnifico.

While it is plausible that the Nascita di Venere was directly commissioned by Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco for the Villa di Castello, we cannot exclude with certainty that it arrived there only later from a different patron.

In any case, scholars have noted how the cool, almost pastel hues of the canvas – together with its imposing dimensions (172.5 x 278.5 cm) – make it more similar to a wall painting. In other words, the Venere by Botticelli was intended to simulate a fresco, probably placed not too far from the floor.

Regardless, after Vasari, the canvas is cited in the villa’s inventory of 1589 and in all subsequent ones up to 1761, always accompanied by a frame currently lost, before arriving at the Uffizi in 1815.

The meaning of the Nascita di Venere

The Primavera and the Nascita di Venere are linked not only because they were seen together by Vasari or because they are works by the same artist, but because they share the same ideological program.

Despite differences in format, technique, and medium (the Primavera is painted on panel, while the Venere is on canvas), some experts believe both refer to Neoplatonism, the philosophical doctrine of Marsilio Ficino, an intellectual active at the Medici court.

In a letter written in 1477 to the young Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco, Ficino exhorts his disciple to follow the virtues of Humanitas embodied by Venere, symbolizing spiritual love and beauty. The nudity of the goddess, far from being erotic, would thus be a means for intellectual and divine contemplation. This well-regarded explanation does not negate the “elusiveness of meaning” attributed to the two paintings by Ernst H. Gombrich – one of the proponents of this theory.

Erwin Panofsky also believed that the works represent the two visions of Neoplatonic love: spiritual (the Nascita di Venere) and earthly (Primavera), and that they were intended as such by Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco. Yet, Panofsky recognizes that all critical interpretations end up being complementary rather than alternative, enhancing the charm of these still undeciphered masterpieces.

Are you interested in articles like this?

Sign up for the newsletter to receive updates and insights from BeCulture!

Curiosity: Botticelli’s reconsideration

In 1987, the restoration of the Nascita di Venere was completed, masterfully conducted by Alfio Del Serra. The effort aimed to improve the painting’s conservation conditions and restore its original appearance as much as possible, mitigating the effects of time and clumsy subsequent interventions. The public was thus able to better appreciate the compositional harmony, colors, and the subtle and elegant lines characteristic of Botticelli, fully enjoying the work.

Some curious aspects unexpectedly emerged during infrared reflectography analyses, revealing the presence of stylistic corrections in the preparatory phase: modifications to the size of Venere’s eyes and Zefiro’s torso. The most significant reconsideration, however, concerns the overall dynamism of the scene, which – according to the initial drawing – was intended to appear much less animated. The cheeks of the wind god appear less full, the mantle carried by the maiden less billowing, and Venere’s hair less disheveled. This last detail suggests that Botticelli, in the final phase of the painting, may have revised it, possibly influenced by the aforementioned writing of Alberti, who recommended depicting hair moved in every direction by the wind.

But once again, we are faced with a hypothesis – a paradoxical situation when considering it involves one of the most important works of the Italian Renaissance, which also holds another record: the Nascita di Venere is the first existing example in Tuscany of large-scale canvas painting.

To see it in person, all you have to do is book your ticket for the Uffizi!

1. De pictura (Sulla Pittura) is a treatise in three books written in 1435 by Leon Battista Alberti (1404–1472), a polymath Renaissance architect and humanist.

2. An artist, architect, and man of letters at the Medici court, Giorgio Vasari (1511–1574) was also the author of Le vite de’ più eccellenti architetti, pittori, et scultori italiani, da Cimabue insino a’ tempi nostri (published in 1550 and in 1568 with additions), a fundamental work for Italian art historiography.