A newfound interest in nature and the legacy of medieval symbolism are the keys to interpreting Renaissance paintings in which animals appear. The figurative art of this period focuses on a realistic depiction of the world while still preserving the rich repertoire of metaphors and allusions inherited from earlier times. As a result, cats, dogs, birds, and exotic species make their appearance in the works of 15th and 16th century painters, carrying meanings that can sometimes seem obscure to us today. This brief journey through Renaissance zoology helps us decode those meanings and better understand the artists’ intentions.

The dog, humanity’s most loyal friend

It’s hard to think of a more common animal than the dog, which in Western tradition has almost always held a positive connotation. Dogs appear in both religious and secular iconography, but they are especially recognized as a symbol of loyalty in 15th and 16th century portraiture.

A well-known example is the The Arnolfini Portrait by Jan van Eyck (1434, National Gallery, London). A small dog stands in the lower part of the painting, right where the couple’s joined hands are, a clear reference to marital fidelity.

A similar meaning appears in depictions of single figures, such as the Ritratto di Eleonora Gonzaga, duchessa di Urbino (c. 1537) and the Venere di Urbino (1538), both painted by Tiziano and now housed in the Galleria degli Uffizi in Florence.

Although these two canvases differ greatly, they share the presence of a little dog curled up beside each woman, symbolizing constancy and devotion in love. This is hardly surprising, given Tiziano’s fondness for this animal, which he depicted in over 30 variations across his works.

Yet the dog hasn’t always been portrayed solely with positive attributes. A good example is the Giovane cavaliere by Vittore Carpaccio, which was mistakenly attributed to Dürer until 1919. There are two dogs in the painting: one stands near the mounted knight in the background, symbolizing loyalty once again, and another, a stray and threatening dog, sits at the foot of a tree on the right. This second dog represents the adversities the knight has yet to overcome, contrasting with the knight’s purity of heart, symbolized by the white ermine in the lower left corner.

The cat, a portent of misfortune

As is well known, cats and dogs don’t get along very well, and this notorious rivalry is depicted in some representations of the Ultima Cena, where the two animals face off under the table to illustrate strife and hostility. Cats are also frequently associated with betrayal (and thus often placed at Giuda’s feet), the devil, and lust.

An emblem of impurity, the cat also appears on the wooden platform in San Gerolamo nello studio by Antonello da Messina (c. 1475, National Gallery, London), right below a dirty towel that conveys the same meaning. Opposing the cat are the lion – an iconographic attribute of the saint, visible to the right in shadow – and the two birds in the foreground: a partridge, linked to San Girolamo, and a peacock symbolizing purity.

In the Annunciazione by Lorenzo Lotto (1527, Pinacoteca Comunale in Recanati), the cat stands out for its spontaneity and adds a dash of measured humor to the scene: it jumps away, startled by the commotion caused by the angel’s sudden appearance announcing Christ’s birth to Mary.

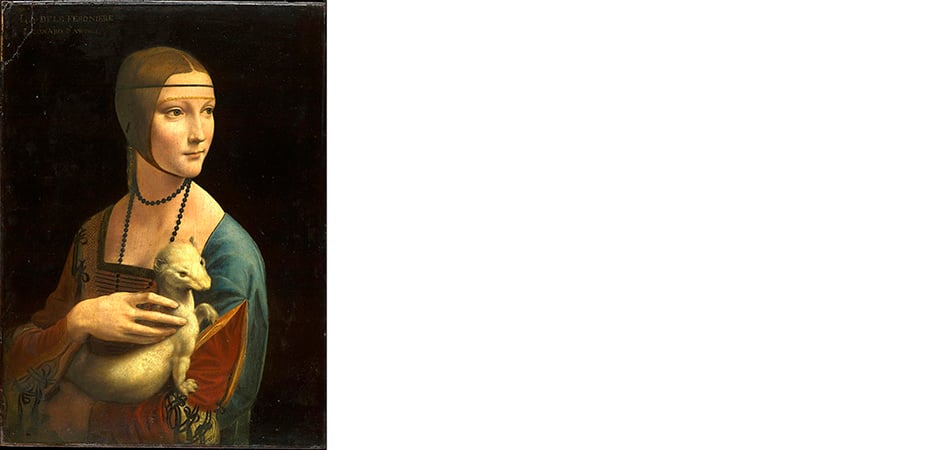

The ermine, symbol of female purity and chastity

We don’t see what agitates the ermine in the famous portrait Dama con l’ermellino by Leonardo Da Vinci (1490, Czartoryski Museum in Kraków), as it squirms in the arms of Cecilia Gallerani. In reality, the creature is a ferret – since true ermines cannot be domesticated – but it evokes chastity and purity: according to an ancient belief, an ermine would die if its pristine white coat were ever stained. For this reason, it can also be associated with the Virgin Mary and other virgin saints, who are sometimes depicted wearing ermine fur.In Leonardo’s portrait, the little animal enhances the virtues of Ludovico Sforza’s (the Duke of Milan) young mistress, herself a poet and close to the intellectual circles of the time. Besides underscoring her courtly qualities, the ermine also carries special meanings: it is one of Ludovico’s emblems, and its Greek name (galé) echoes the first letters of Gallerani, subtly suggesting the subject’s identity.

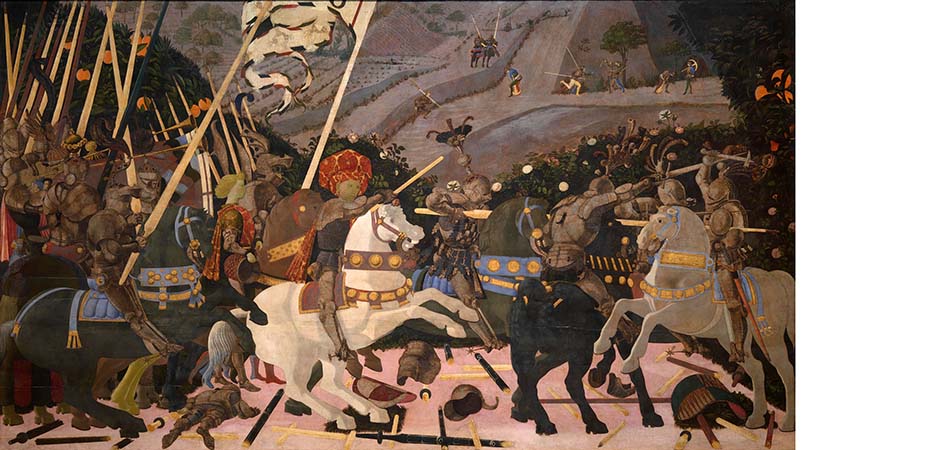

The horse: between celebration and doom

Renaissance portraits of knights, kings, and nobles on horseback serve a distinctly celebratory function. The horse itself was a subject of close observation by Leonardo da Vinci and earlier by Paolo Uccello, as seen in his majestic triptych, La Battaglia di San Romano. Yet a horse can symbolize more than just strength and vitality; it can also take on negative connotations. This is the case with the pair of horses depicted by Hans Memling in his Diptych with the Allegory of True Love (1485–1490), now split between New York and Rotterdam. On the panel in Rotterdam, we see a dark horse, originally turned toward the lady in the American panel, and a white horse drinking with a monkey on its back. The monkey alludes to base appetites that force the horse to give in to instinct, rejecting noble love in favor of raw passion.

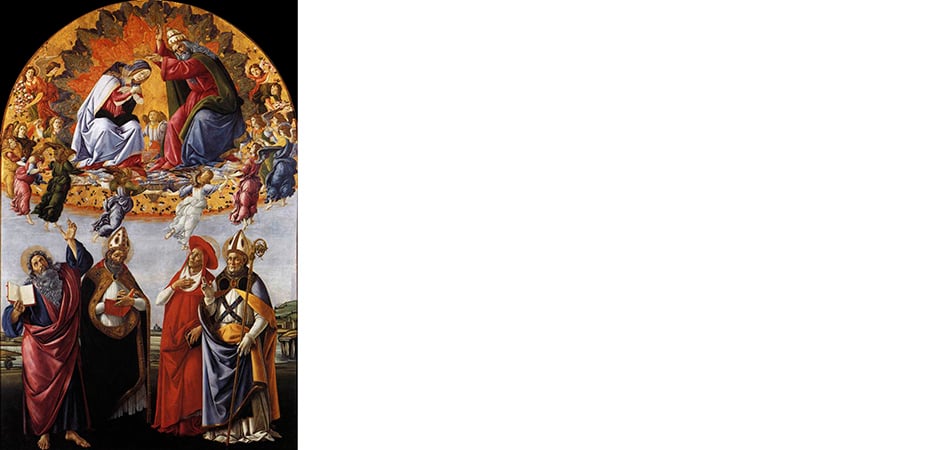

Horses, moreover, can be possessed by the devil – who can even have hooves like a horse – and thus need deliverance. That is precisely the task of Sant’Egidio in the predella of the pala di San Marco by Botticelli (1490–1492, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence). The scene of Miracolo di Sant’Egidio shows the saint shoeing the severed hoof of a demon-possessed horse – featured in the same panel – to heal the animal.

The goldfinch, symbol of Christ’s sacrifice

Besides the dove, the traditional symbol of the Holy Spirit, other birds enliven 16th century paintings. One of these is the goldfinch, a small bird with brightly colored plumage that, in religious works, serves as a foreshadowing of Christ’s Passion. According to tradition, its Latin name, carduelis, derives from its fondness for thistles – spiky plants that evoke the crown of thorns.That symbolism is evident in the Madonna col Bambino e San Giovannino, detta Madonna del Cardellino by Raffaello (1506, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence), where a young Giovanni presents a fragile goldfinch to the Gesù under the watchful eye of the Virgin.

The parrot, a many-tongued creature

Thanks to its remarkable ability to mimic human speech, the parrot – an exotic species – carries mainly positive connotations and is often linked to the Virgin Mary and the Annunciation. Hans Baldung Grien’s intriguing painting The Madonna with the parrots (c. 1527, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg) illustrates this symbolism: it was thought that parrots could say the word “Ave,” the archangel Gabriele’s greeting to Maria, which explains the bird’s presence near the nursing Christ Child. Meanwhile, a second parrot biting the Virgin’s neck is believed to reference the Immaculate Conception.

In Battesimo di Cristo by Giovanni Bellini (1500–1502, Church of Santa Corona, Vicenza), a striking red parrot appears next to San Giovanni, representing the saint’s prophetic role – like the parrot, he repeats someone else’s words (in his case, God’s).

Are you interested in articles like this?

Sign up for the newsletter to receive updates and insights from BeCulture!

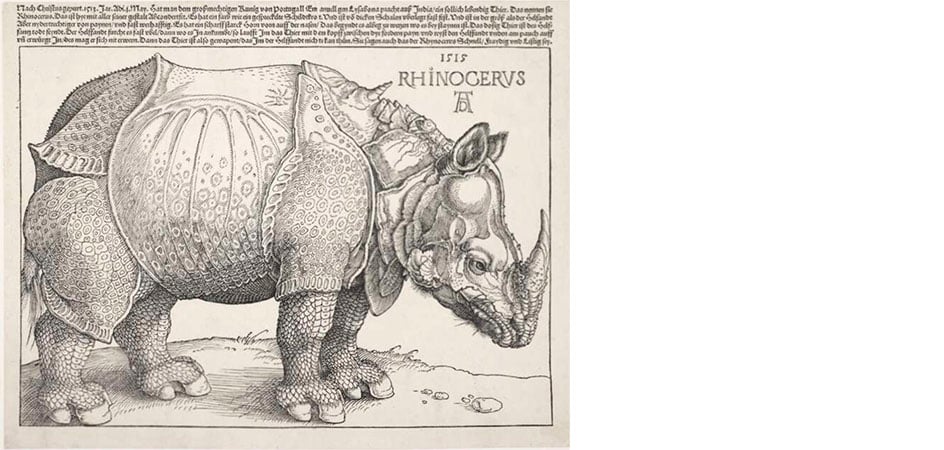

The rhinoceros: a Renaissance curiosity

Among the animals featured in Renaissance art, one rhinoceros deserves special mention. The story begins with Rhinoceros (1515, British Museum, London), a woodcut by Albrecht Dürer, renowned for his drawings and self-portraits. Beyond its artistic merits, this work has historical importance because it documents the first time Europeans had encountered a rhinoceros since ancient Roman times.

A gift from Sultan Muzafar of Cambay to King Manuel I of Portugal, the rhinoceros arrived in Lisbon on May 20, 1515. Originally from India, it was still alive when King Manuel decided to send it on to Pope Leone X. Unfortunately, things went awry on the long sea voyage and the ship carrying the rhinoceros sank in the Gulf of Genoa. The animal reached its destination stuffed, and Dürer – who was in Nuremberg – never saw it in person.

Instead, he relied on a sketch and a description to create his own vision of the creature. It’s thanks to the artist’s imagination that we have the small horn on the rhinoceros’s back, its scaly skin, and a kind of armor plating—details that made the beast even more fascinating and exotic to contemporary viewers. Since then, Dürer’s famous Rhinoceros has captivated many artists and has been copied and reinterpreted through the centuries.

Animals in Renaissance art are never mere decorative touches but rather silent protagonists of a deeper narrative. Straddling symbolism and realism, they embody virtues, vices, and spiritual values, serving as keys to decipher the era’s imagery and the worldview of its artists. It’s a dialogue between nature and culture that continues to enthrall us, revealing the rich layers of meaning within Renaissance painting.