The Venere di Urbino by Tiziano is not just one of the masterpieces of the 16th century, but it is also among the most enigmatic paintings in the history of art. Its iconographic power is confirmed by its acclaimed fame among artists of all times. Perhaps it’s because of the soft nudity, the mysterious identity of the young woman, and its still obscure meaning.

Today, the painting is preserved at the Galleria degli Uffizi and is undoubtedly one of the good reasons to visit the museum. In this article, we revisit the genesis and analysis of the work to fully enjoy its beauty and complexity when viewed in person.

The commission

One of the few things we know for sure about the Venere di Urbino is the year it was purchased, 1538. This is confirmed by correspondence that took place in the spring when its commissioner, Guidobaldo Della Rovere, Duke of Urbino, communicated with Gian Giacomo Leonardo, the ambassador of Urbino in Venice. In the first of these letters, Guidobaldo instructs his agent, Girolamo Fantini, to retrieve the two paintings made for him by Tiziano: his portrait and ‘the nude woman’, as he refers to the painting. He insists that Fantini “leave Venice with no one’s account but his own without bringing them”. Regarding payment, the duke continues, he guarantees it will be made and that if he cannot attend to it himself, his mother, Eleonora Gonzaga, will settle the debt with the painter.

However, something goes wrong because a few months later, the lord of Urbino finds himself writing to the ambassador again, demanding the delivery of the second painting, the Venere. He promises to pledge something of his own in exchange. We can suppose that Gonzaga – a God-fearing mother – had readily agreed to pay for her son’s portrait but not for the nude woman. A subject that Guidobaldo was not willing to give up and which, in a manner unknown to us, he finally managed to obtain.

Ten years after the acquisition, the canvas was admired in the Wardrobe of the Dukes by Giorgio Vasari, who first identified it as a Venere. Indeed, we owe the name of the work now at the Galleria degli Uffizi to Vasari and the painting’s provenance. Following the marriage of Vittoria della Rovere, the last of the house, to the Grand Duke of Tuscany Ferdinando II de’ Medici, this and other works from the collection were transferred to Florence.

For a long time, the Venere di Urbino was displayed in the Tribuna degli Uffizi, next to the so-called Venere dei Medici, probably to juxtapose two different interpretations of the same subject: the classical and ideal beauty of ancient sculpture and the sensual, fleshly beauty of the 16th century painting.

Are you interested in articles like this?

Sign up for the newsletter to receive updates and insights from BeCulture!

Analysis of the Venere by Tiziano: the subject, identity and meaning

The erotic charge of the woman depicted is immediately apparent, so much so that during the time of Grand Duke Cosimo III, it was judged excessive, and a mobile cover was employed. When exhibited to the public, the Venere was protected by an overlying canvas, painted by Carlo Sacconi with the allegory of Amor Sacro and the Amor Profano, which only left the woman’s head and one arm uncovered. Through a mechanism, it was possible to lift the curtain and thus reveal the full nudity. This device remained functional until 1748, but it did not prevent the work from being the most copied at the Uffizi by the end of the 18th century, alongside the classical Venere and the paintings by Raffaello.

The reason for this success is found in the composition and excellent execution, as well as in the halo of mystery that envelops the identity of the model and the ultimate meaning of the painting.

What the Venere di Urbino represents

On an unmade bed (a pair of red mattresses covered with wrinkled white sheets), lies a young naked woman. Her figure occupies the entire foreground of the large canvas (119 x 165 cm), almost life-size. In her right hand, near her breast, she holds a small bouquet of flowers, likely roses, while her left hand conceals her pubis. Her face and gaze are turned towards the viewer and seem to suggest an invitation to participate in the scene. The bracelet with precious stones and enamels, the baroque pearl in her ear, and the ring on her little finger are all she wears. At the young woman’s feet, a small dog is curled up sleeping.

The background is divided into two parts: on the left, beyond the young woman’s back, a knotted curtain and a dark wall block the view, while on the right, the interior of a domestic setting opens up with decorated walls and a window. In the corner of the room, two maids are busy retrieving the woman’s clothes: one standing, holding a dress over her shoulder, while the other, bent over and with her back turned, rummages inside one of the storied chests. On the windowsill, in silhouette, a myrtle plant is visible.

Possible interpretations

Over the centuries, there have been many divergent critical readings, and the meaning of the work remains obscure to this day. The most accredited interpretation is that it was a wedding gift to celebrate the union of Guidobaldo with Giulia da Varano, who is also portrayed in another painting (not all attribute it to Tiziano) preserved at the Galleria Palatina of Palazzo Pitti in Florence. The subject would thus be a young woman preparing to partake in the Venetian tradition of the “toccamano”: where brides-to-be expressed their consent to the marriage by touching the hand of their future husband.

The myrtle plant, associated with the goddess of love, and the small dog, would thus be symbols of marital constancy and fidelity.

However, some argue that the chronological succession does not reconcile well with the matrimonial reason, since the marriage between Guidobaldo and Giulia da Varano took place four years before the acquisition of the painting. Nonetheless, the motif of the nude woman was not entirely new in patrician houses and was used in painted chests with a propitiatory function. The depiction of Venere was meant to promote procreation and ensure beauty in offspring with her gaze, or even facilitate the excitement of lovers.

Tiziano’s goddess also recalls the iconographic theme of the Modest Venere, created by Praxiteles in the mid-fourth century for his famous Aphrodite of Knidos and subject to numerous subsequent reinterpretations. Renaissance artists, attuned to the allure of classical archaeology, often applied this iconographic model (one hand to the breasts and one to the pubis) to sacred or profane female figures caught in a moment of shame. This is confirmed by, among others, the Venere by Botticelli.

The identity of Venere

Who was, in real life, the woman immortalized by Tiziano?

Many attempts have been made to identify her: some thought she might be the painter’s lover. Others, seeing a resemblance of Venere‘s dog to that in the Ritratto di Eleonora Gonzaga by Tiziano, speculated she might be the Duchess of Urbino. Yet others proposed that the subject was the same as in the Ritratto di gentildonna (known as La Bella), also visible at the Uffizi.

It is true that the jewels of Venere are roughly identical to those of other ladies painted by the Cadore painter, and even the dog, as a subject, is among the most recurrent in his painting (he painted more than thirty!). As significant as these details are, they are not conclusive evidence for the biographical reconstruction of the woman.

What is striking about the painting is the prototype of femininity promoted by Tiziano, in stark contrast to that developed in the same period by Michelangelo.

The poet and intellectual Pietro Aretino wrote of the latter that he was accustomed to placing “the muscles of a male on the body of a female.” Indeed, the women of one and the other could not be more different: voluptuous, soft, sensual is the Venere of Vecellio; athletic, solid, and sculptural are those of Buonarroti. A comparison between two models that continued, fiercely, even in subsequent eras.

Vasari even recounts a probably invented encounter that took place between the two rivals in Tiziano’s studio. According to the historian, during the visit, Michelangelo uttered these words: “It’s a pity that in Venice one does not learn from the beginning to draw well, and that those painters did not have a better method in their studies.”

A discredit that was not shared by all if, even in the 20th century, the Venere di Urbino was the object of more or less explicit references.

Beyond the Venere di Urbino: precedents and legacy

The theme of the reclining nude is not an invention of Tiziano. During his years in Rome, the painter probably had the chance to see examples of ancient Roman, Etruscan, and Greek nudes.

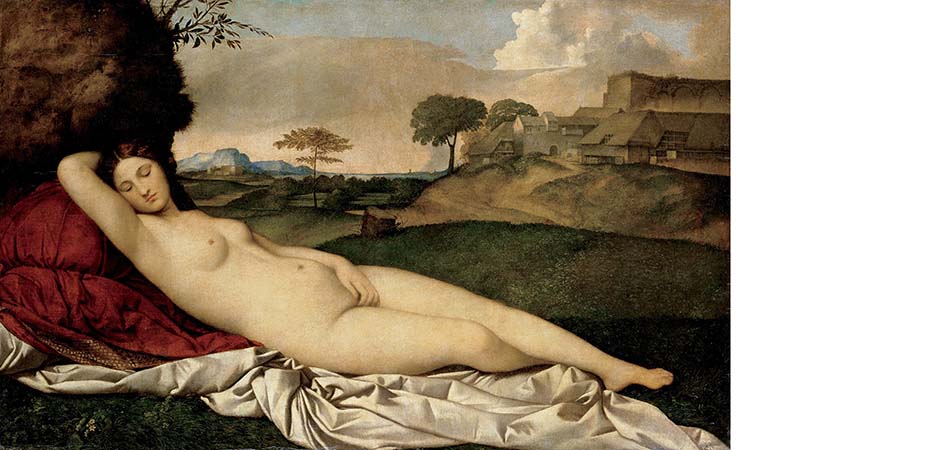

In tracing the precedents of the Venere, we cannot fail to mention the Venere dormiente by Giorgione, also known as the Venere di Dresda, after the location where it is kept today, the Gemäldegalerie of the city. Begun by Giorgione and finished around 1510 with the help of Tiziano, his collaborator, the state of conservation of the painting—having undergone numerous restorations over the years—does not allow us to distinguish precisely which parts were painted by which artist. The resemblance is clear, albeit with some substantial differences: the Venere by Giorgione is, in fact, asleep, lying on a resting place in the midst of an open landscape, her left hand on her pubis and the right supporting her head.

The Venere by Tiziano, as we have seen, is awake, alluring, and set in a real context: the interior of a typical Venetian house. The Venere di Urbino explicitly refers to the Dormiente, but changes the sign: from idealized purity to inviting sensuality.

Many subsequent artists have drawn on the iconography and more generally on the theme of Venere, with references and homages varying according to the era and personal style.

The 17th century is characterized by an exaggeration of forms, with the female body arranged in increasingly bold poses: from Venere e Cupido by Guido Reni, to Cleopatra by Artemisia Gentileschi, to the Venere Rokeby by Diego Velázquez, where the goddess is presented to the viewer from the back, in a completely innovative way.

A more frivolous and carefree sexuality is proposed by Jean-Honoré Fragonard in his paintings, in a century—the 18th—that closes with Canova’s sculpture of Paolina Bonaparte, where the divinity has a first and last name.

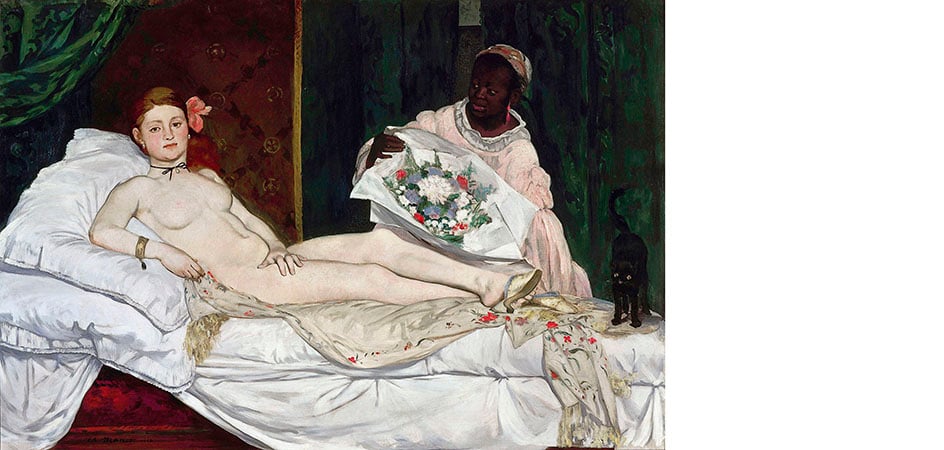

The 19th century, on the other hand, opens with the Maja desnuda and Maja vestida by Goya where the provocative intent is explicit, while Romanticism is tinged with orientalism with Ingres’s odalisques. Goya and Tiziano are the precedents for Olympia by Manet which transforms the goddess into a prostitute, complete with servitude.

With the Impressionists, the female nude gains a more natural dimension, while for the historical Avant-garde it will become the pretext for expressing their own style through the theme.

The motif of Venere in art certainly does not end here (just think of the Venere degli stracci by Pistoletto). But the theme is also the origin of prosaic and commercial variants, filling advertisements and social networks. Who knows how many of these owe a debt to Tiziano, and to all the Veneri that preceded him.