Home / Experience / Benvenuto Cellini

Benvenuto Cellini

A Florentine goldsmith, sculptor and writer, Benvenuto Cellini is undoubtedly one of the outstanding artists of the Mannerist panorama. Determined and sanguine, his life is a continuous alternation of marvellous creations and episodes of violence and crime.

Youth and education – An irascible character

Son of Giovanni d’Andrea di Cristofani and Elisabetta Granacci, he was born in Florence in 1500 and grew up in a wealthy home. His father, as Cellini recalls in his autobiography, worked occasionally as an engineer designing scaffolding, machinery for wool processing and various devices, and was also the official Piffero of the city orchestra. It is no coincidence that little Benvenuto began studying music at a very young age.

At the age of 13, he was sent to the workshop of Michelangelo Bandinelli and later, in 1515, to Antonio di Sandro, known as Marcone, both goldsmiths of the highest level. In the meantime, however, despite his obvious talents as a draughtsman, he was forced by his father to reluctantly continue studying music, who wanted a bright future for him in the field. Already in his early teens, he showed signs of an irascible, grumpy and often violent character, characteristics that were to mark his entire life: at only 16, he was exiled to Siena following a brawl, and there he stayed for several months cultivating his true passion: goldsmithing.

He returned to Florence, was sent to Bologna by his father to continue his instrumental studies for a short time and, despite his evident lack of interest in music, was once again forced by his father to continue his instrumental studies in Bologna. In the capital of Romagna he comes into contact with the goldsmith environment and continues his improvement. He returned to Florence in 1517 but after a very short time he fled to Pisa for reasons that not even he specifies that could have to do with the family. From this moment on we find him almost everywhere in central Italy: alternating stays and apprenticeships between Florence, Siena and Rome at various goldsmiths and almost always following brawls or violent crimes. During these years he was able to study the preparatory cartoons and drawings of Leonardo and Michelangelo, to make sketches from life of old Roman ruins and to get to know the young assistants in Raphael’s workshop.

The first independent years: between the Church and violence

In 1523 the first crime of which we have documentation takes place: a death sentence for having stabbed a rival goldsmith. Having fled to Rome, he was well received in the papal capital where he began to work independently relying first on the workshop of Lucagnolo da Jesi, then on that of Giovan Francesco della Tacca.

Forced by circumstances to comply with the much despised will of his father, he gives in to a musical career and enters the fanfare of Pope Clement VII as a cornetto player. The stability provided by the salary as an orchestrator and the increase in goldsmith commissions, in 1524, allow the young Benvenuto to open his own workshop,

His stay, and his success, in Rome lasted until 1527, until the Sack of Rome. This historic siege is a fundamental watershed in the history of art, as it will cause a real diaspora of artists from Rome to the other Italian courts. In the case of Benvenuto Cellini, the story is even more interesting: always led to physical confrontation, he takes an active part in the defense of the city and, taking shelter together with a part of the papal army inside Castel Sant’Angelo, kills the Duke Charles of Bourbon and wounds the Prince of Orange. After the battle he manages to leave Rome and return to Florence.

The years of pilgrimage

As with many artists of his time, for Benvenuto a series of long years began, spent jumping from one city to another, from court to court in search of patrons. Despite the many documented works, but now lost, he still fails to emerge, forced to create works of little relevance. In 1528 he was in Mantua, where he created, among other small goldsmith works, a seal for Cardinal Ercole Gonzaga. The following year he returned to Rome as “master of prints” with the task of supervising the state mint and on the occasion he created a goblet for Clement VII. It seems that the time has come for Cellini to re-establish himself at the papal court. As will often happen in the life of this rebellious artist, the circumstances will unfortunately be very different. In 1531 he killed his brother’s killer in revenge but this time he was pardoned by the pope. The following year, he reopened his shop in Rome but the pope deprived him of his protection and two years later he fled to Naples after having attacked and beaten a notary.

Little remains in the Neapolitan city, while he works on a medal to regain the pope’s trust. Having shown the work to Clement VII, he was able to return to Rome but in the same year, 1534, he once again killed a rival goldsmith, Pompeo de’ Capitaneis. Luckily for him, a new pope, Paul III, has recently ascended the papal throne, who pardons him. Despite the safe conduct, he ends up in the crosshairs of the pope’s son Pier Luigi Farnese and is forced to flee again, this time returning to Florence. Here he has the opportunity to admire the New Sacristy by Michelangelo, an artist who over the years had impressed Benvenuto more than any other. Following yet another quarrel, this time with Ottaviano de’ Medici, a distant cousin of the branch of Lorenzo the Magnificent, he returned to Rome. The story of Cellini’s life seems increasingly tangled but, thanks to this new stay in the city, Pope Paul III commissions him to make a tribute to the emperor Charles V: the engravings for the cover of an official, or a book of prayers, lost today. Hence the first turning point: slowly he managed to carve out his own space within the European courts, also staying in Paris, perhaps on a commission from the French king Francis I. In 1537 he returned to Rome.

Once again he ends up in trouble with the law: in 1538 he is accused of having taken advantage of the tragedy of the Sack of Rome to steal jewels from the previous pope and is thrown into prison. He manages to escape almost immediately but already the following year he is behind bars again. He is finally freed and leaves for Ferrara where he works for Cardinal Ippolito d’Este. later, for many more years, he continued to wander between Italy and France, at least until an unexpected turning point.

The Salt Shaker and the long-awaited glory

During his last, and most extended, stay at the court of the King of France, he created the first work still preserved today and which would make him famous in all the courts of Europe: the Salt Cellar of Francis I. This splendid gold object, ebony and enamel unequivocally shows his remarkable skills as a goldsmith, his compositional skills, as well as his knowledge of the sculptural models of his beloved Michelangelo. Not just a beautiful ornament, the Salt Cellar is a real work of art, a miniature sculpture, and clearly shows the signs and style that will later be known as Mannerism.

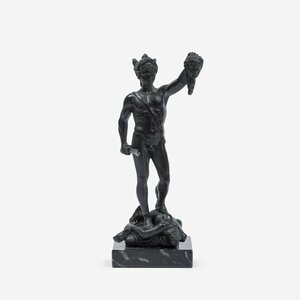

Now a recognized artist, finally, in 1545 he managed to return permanently to his hometown, welcomed by the Grand Duke Cosimo I who appointed him the official court sculptor. The choice of the Grand Duke may seem risky, considering that only the saltcellar remains from that period, but from the sources of the time we know instead that during the French stays the artist had dedicated himself to the creation of large works in bronze. Specifically, he had been commissioned to make twelve gigantic torchlight statues for the left bank of the Seine. Cosimo I therefore commissioned Cellini to make his own bust in 1548, now in the Bargello National Museum, and finally, his most famous work: Perseus with the head of Medusa.

The Epic of Perseus

The Perseus project is undoubtedly the most ambitious of his career. The goal is to create a bronze colossus, over three meters high, almost six if you count the richly decorated base, which combines the skillful craftsmanship and attention to detail of the goldsmith with the strength of Michelangelo’s statuary. Studying the ancient bronzes, he aims to melt the statue into just three pieces to be welded together. In his autobiography Cellini tells in detail the hard fight against his own work, the battle that was its realization. While working at Perseo, he is blackmailed by the mother of one of his shop assistants with whom he was suspected of having a homosexual relationship. The woman tries to extort money from him but Benvenuto is certainly not the type to be intimidated and, after threatening her with a knife, flees to Venice with the young man where he stays for some time. Back in the city, he creates the head of Medusa, the first piece of the puzzle. Short of collaborators and with his reputation ruined by the slanders of his opponents, he continues undaunted to work on his masterpiece. Suddenly he is seized by violent episodes of fever, perhaps caused by exposure to the toxic fumes produced by the smelting of metals, but he does not give up. As if that weren’t enough, the shop’s furnace gradually begins to lose heat due to a heavy storm, further slowing down the fusion. Once the equipment has been brought back to its optimal state, the fusion of the alloy for the remaining parts is too dense for casting and the artist, in a last desperate gesture, melts all the tin pots he has at home to be able to obtain the correct density .

It must be said that, in hindsight, the enormous effort of Benvenuto Cellini has borne the hoped-for results. The Perseus surprises for its power, for the hero’s wriggling muscles and for the attention to the smallest anatomical and decorative details. Here we have the perfect summa of the classical echo of the Renaissance proper and of the serpentine, articulated and languid figure typical of Mannerism. An encounter between the power of Michelangelo and the grace of Donatello, all seen through a new, modern, essentially unique lens. In this marvelous work we find the extraordinary practical rendering of Cellini’s theory of views: according to the artist, a work of sculpture, in order to be defined as complete, must have at least eight views, each of equal quality. In short, it must be admirable at 360 degrees.

The last years

After the realization of Perseus, Benvenuto Cellini enters into a rout with the Grand Duke and thus ceases his collaboration with Cosimo I. In his place others enter the good graces of the powerful monarch, probably due to their more condescending character and total adherence to the program Florentine culture: Baccio Bandinelli and Bartolomeo Ammannati. Unable to work anymore, he began writing his memoirs, now known as La Vita.

Benvenuto Cellini died in Florence in 1571, after having donated all his unsold works to the Grand Duke Francesco I de’ Medici.

Cover photo: Perseus with the head of Medusa, 1545, Benvenuto Cellini, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence

Florence, 1500 – Florence, 1571

Jewellery, sculpture and writing

Related products

Related museums

From €16,00

Originally the residence of the wealthy Florentine banker Luca Pitti, this magnificent palace was purchased in 1550 by Grand Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici, who established his court there with his wife Eleonora of Toledo. After two centuries, from 1737, the palace was to be the residence of the Lorraine family, who succeeded the Medici in the Grand Duchy, and later of the Savoy family during the five years when Florence was the capital of Italy.

Average visit time:

2 hours