An unparalleled work, the Tondo Doni by Michelangelo represents a unique piece not only in art history but also within the artist’s body of work. The painting, already an exception in Michelangelo’s Florentine experience, is the only completed piece on a movable support unanimously recognized as his by critics.

Moreover, quoting the famous art historian Federico Zeri, it is an “absolute iconographic novelty, a synthesis of the various art forms Michelangelo dedicated himself to. A great painter, excellent sculptor, and supreme architect, Michelangelo achieved in this one work what other artists would take decades to accomplish and, with extraordinary precocity, anticipated the style of the frescoes on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel”.

Let’s explore what this “supreme gem of the Uffizi in Florence” represents.

Iconography and interpretation beyond the subject

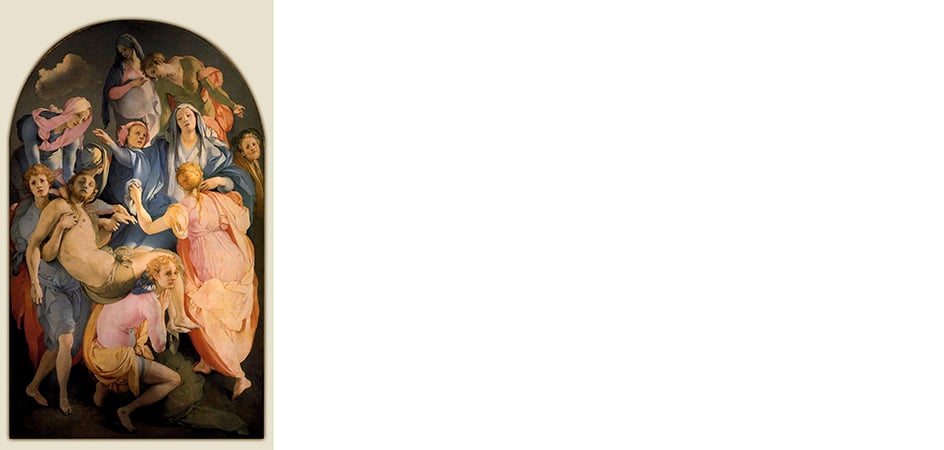

The Tondo Doni depicts the Holy Family: the Virgin, in the foreground, sits on the ground according to the 14th century iconographic motif of the Madonna dell’Umiltà. Behind her, a robust San Giuseppe either offers (or receives, the gesture’s interpretation is uncertain) the Bambino. In the background, beyond a low wall, San Giovannino with a cross of branches gazes ecstatically at the group, while behind them, five nude men occupy the background: two on the left in a contemplative attitude and three on the right, sterner and more dynamic.

The subject itself might not need explanations, but the presence of the so-called Ignudi has led to various critical interpretations. The most accredited one is that Michelangelo intended to depict humanity’s development from pagan antiquity to Christianity. The nude youths symbolize the ante legem period, before the Decalogo; Maria and Giuseppe belong to the sub lege world, the world of the Leggi di Mosé and the Vecchio Testamento, while the Bambino represents the sub gratia world, illuminated by Grazia Divina. A wall separates the two worlds: San Giovannino is beyond it but looks towards the truth, acting as a mediator for humanity’s salvation.

Michelangelo felt more like a sculptor than a painter and here demonstrates the perfect fusion of both arts. The bodies are powerful, voluminous, and solid, almost sculpted under the draperies. This is the first time the Vergine shows such muscular, almost masculine, bare arms, twisting in a novel and henceforth iconic movement. This is where the serpentine figure, so beloved by Mannerism, originates.

Another innovation introduced by Michelangelo: the colors. Bright, glossy, acidic, almost shrill and magnetic, in stark contrast to the chromatic and rarefied atmosphere of the background. These tones would inspire many artists, starting with Pontormo (see, for example, his Deposizione of 1526-27, in Santa Felicita in Florence) and Rosso Fiorentino (just look at his Mosè difende le figlie di Jetro, 1523, at the Uffizi).

The commission and dating issue

The Tondo Doni gets its name from the circular format of the panel, popular in the Tuscan Renaissance environment, and from its owner. We know that Agnolo Doni, a wealthy Florentine cloth merchant, commissioned the work from Michelangelo. We also know that, due to his stinginess, he ended up paying exactly double what the artist initially requested. This episode is recounted by Vasari in the chapter of his Vite dedicated to Michelangelo. The biographer architect reveals how, to lower the price, Doni aroused the irritation of the painter (known for his fiery temperament) who, in retaliation, doubled it. Thus, instead of only 70 ducats, Agnolo Doni paid 140!

But on what occasion was the panel produced?

For a long time, it was thought to be a painting made in 1506 to celebrate the marriage between the merchant and the aristocrat Maddalena Strozzi, which took place two years earlier, in January 1504, in Florence. The delay between the event and the delivery of the work was not unusual for the time and even Raffaello had portrayed the Doni couple in the same period.

This dating of the Tondo derives, in particular, from two considerations.

The first is the presence on the wooden frame of the Strozzi coat of arms (three crescents, at the top left), surrounded by four lion heads, probably referring to that of the Doni (the rampant lion): an allusion to the union of the two families.

The second consideration concerns the analogy between the Tondo Doni and the Deposizione Baglioni (or Deposizione Borghese, now in the Galleria Borghese in Rome) completed by Raffaello in 1507. According to this hypothesis, Michelangelo’s Vergine’s position would have inspired the supposedly later figure of the young woman supporting Maria in Raffaello’s painting.

The 1504 and 1506 dates would thus be the chronological boundaries of Michelangelo’s panel.

However, stylistic aspects and content suggest a different, slightly later dating.

Besides the colors and the treatment of the bodies that anticipate the results of the Cappella Sistina, started by Michelangelo in 1508, there is another element that suggests a later execution. Critics have noted that all the Ignudi in the background are indebted to Hellenistic sculpture.

Starting with the two on the left: it is not difficult to identify a certain resemblance to classical models like the Apollo seduto of the Uffizi or the Apollo del Belvedere in Rome. On the right, figures similar to the Ercole Farnese and, especially, the Laocoonte can be recognized. The seated man tearing the cloth from the other two while twisting his torso and completely hiding his right arm seems to perfectly cite the pose of the group discovered in Rome in 1506. Michelangelo was almost certainly among the first to see it, sent by Pope Giulio II to assess its quality.

But, if so, it is impossible to date the Tondo Doni before this event. On the contrary, it must have been created at least from 1506 onwards.

How does this theory reconcile with the subject and the life of the patrons? With the birth of their first daughter, which took place in September 1507: Maria, like the Virgin, the absolute protagonist of Michelangelo’s work. Indeed, contemporaries often called the work “Nostra Donna”, confirming the Madonna’s prominent role.

The circular panel, appreciated in the Florentine environment, was used for the birth tray, a painted tray with themes related to Cristo’s birth, offered to women in labor. Moreover, in Giuseppe’s gesture of handing the Bambino to Maria, one can read the allegory of fatherhood and the continuation of one’s lineage: a choice in line with the joyful event.

Are you interested in articles like this?

Sign up for the newsletter to receive updates and insights from BeCulture!

The frame: not a marginal work

Like the painting’s date, the frame – which we now know is original – has also been the subject of studies and suppositions by critics.

The first document attesting to the presence of the frame of the Tondo Doni is a handwritten inventory of the Tribuna degli Uffizi that describes it as: “a wide round adornment all carved and gilded with five raised heads that were part of said ornament”.

In 1780, during the reorganization of the Galleria, it was separated from the Sacra Famiglia and transferred to the Guardaroba. The Tondo Doni was then paired with a modern frame, also gilded and carved, but square. It was not until the early 20th century that the original arrangement was restored, paving the way for hypotheses about the frame’s author.

An artwork in itself, it is today attributed to the carver Francesco del Tasso, but some believe there were at least two executing hands: one dedicated to the grotesque decorations, with masks, griffins, and vegetal elements; and another to the five heads protruding from the medallions.

It is also hard to think that behind such a composite and rich frame, there wasn’t Michelangelo’s mind at work, as some of his drawings preserved in the Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe degli Uffizi and the British Museum in London suggest.

Who the depicted faces are, besides Cristo at the top, we do not know for certain, but a common interpretation is that they are two angels (at the bottom) and two prophets (at the top), probably Isaiah and Micah: the only two who, in the Antico Testamento, prophesy the Messia’s arrival.

Even in what might seem to us today a secondary element, such as the frame, there is thus a precise iconographic program: further testimony – if any were still needed – of Michelangelo’s genius that knows no bounds.