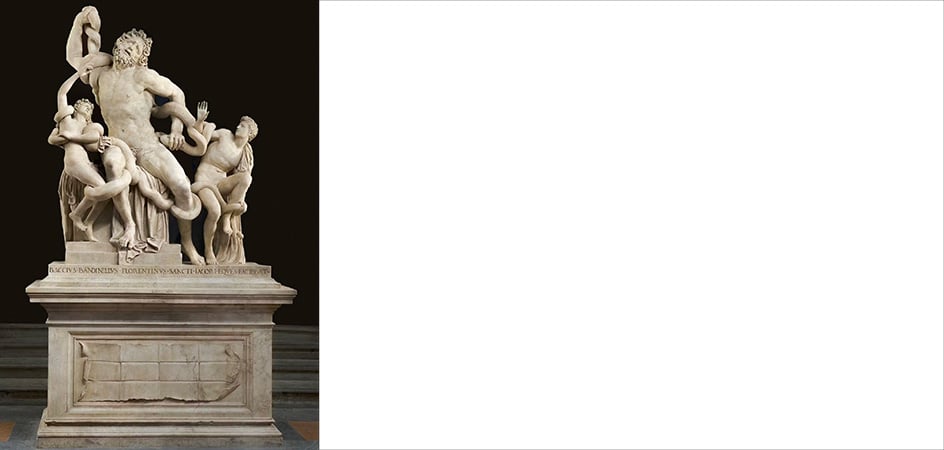

Towering at over two meters and weighing more than two tons, the Laocoonte holds an immeasurable place in the annals of art history. This marble masterpiece, sculpted in the 1st century BC and unearthed in the 1500s, has since become a benchmark for sculptural and expressive perfection. The qualities that define it are just as remarkable today, qualities that have secured the sculptural group’s celebrated status for four centuries. Despite extensive study, it still spurs conjecture and scholarly debate. Let’s delve into the history and significance of the Laocoonte in this article.

What the sculptural group depicts

The dramatic event captured in the sculpture has been recounted by several ancient sources, but it is the 2nd book of Virgilio’s Aeneid that offers the most comprehensive account. It is the tenth year of the Trojan War, and the Greeks, following Odysseus’ cunning plan, feign defeat. They leave a colossal wooden horse on the beach as they pretend to withdraw. The sight of the horse leaves the Trojans bewildered and uncertain. Laocoonte, priest of Neptune, is not fooled. He cautions his people against the Greeks’ infamous treachery and warns of the danger lurking within the horse:

“’Beware of Greeks, even those bearing gifts.’

With these words, he thrusts his mighty spear into the horse’s flank and its curved belly, reinforced with solid plating.”

(Aeneid, II, vv. 49-53)

Shortly thereafter, two gigantic snakes slither from the island of Tenedos, their “eyes aflame with blood and fire”, their “mouths hissing venomously”. They seize Laocoonte’s sons, Antifate and Timbreo, squeezing and consuming them. Laocoonte rushes to their rescue but to no avail. Entwined by the snakes, he too meets a grisly end. The snakes then retreat to the temple of Athena, leaving the Trojans convinced: Laocoonte has been smitten by the goddess for desecrating the sacred horse with his spear – a horse they must now accept within their walls as a divine gift.

The Laocoonte group captures the father and his sons in a futile struggle against the snakes. The figures’ poses, the expressions on their faces, and the tension in their bodies all evoke a profound and poignant pathos. That Virgil inspired this colossal sculpture was immediately recognized by those who first laid eyes on it: Michelangelo and Giuliano da Sangallo.

The Laocoonte discovery and story

On January 14, 1506, the Laocoonte statue was unexpectedly unearthed near Felice de Fredis’s vineyard on the Oppio hill in Rome. The discovery quickly made waves, capturing the attention of Pope Giulio II, an avid collector and aficionado of ancient art. Intrigued by the find, the Pope immediately dispatched Giuliano da Sangallo and Michelangelo to appraise the statue.

There was no doubt in their minds: this was the very sculpture Plinio il Vecchio had described in his Naturalis Historia when he writes: ‘Such is the case with Laocoonte that is in the palace of Emperor Tito, a work to be judged above all others, in painting as well as in statuary (bronze sculpture). It was carved from a single block of marble, with his sons and the marvelous coils of the snakes, by the supreme artists Agesandro, Polidoro, and Atenodoro of Rhodes’.

Plinio was believed to be referring to three Greek sculptors of the 1st century BC, who also crafted another marble group that was only found much later in Lazio. In 1957, four grand sculptures were discovered in the Sperlonga cave, also known as Emperor Tiberio’s grotto. This sculptural ensemble, later known as the Odissea di marmo, once graced the emperor’s cave. The signatures of the three sculptors, Agesandro, Polidoro, and Atenodoro, mentioned by Plinio, are still visible on the ship of the Scilla group.

Further analysis by scholars, noting the signature and the materials, identified similar stylistic features between these sculptures and the Roman figure. This comparison has helped pinpoint the creation of the Laocoonte to the Hellenistic period, now dated to between 40 and 20 BC. Yet, this revelation came much later than the initial discovery.

Pope Giulio II didn’t let this treasure pass him by. After securing the purchase, he had the regal statue placed in a niche within the new Belvedere courtyard of the Palazzi Vaticani, a prime example of an Italian Renaissance garden designed by Donato Bramante.

The association with Plinio il Vecchio and Virgilio, two classical authors greatly revered during the Renaissance, along with the sculpture’s striking expressiveness, contributed to its legendary status: the Laocoonte has profoundly impacted the cultural discourse and artistic landscape of its era.

The Laocoonte’s fame in the 16th century

The discovery of the Laocoonte made waves instantly, captivating not just artists but also poets and scholars, who produced a wealth of opinions and works in tribute to the statue. Celebrated for its vivid realism and emotional depth, the Laocoonte came to symbolize the renaissance of Rome under Pope Giulio II. One of the most striking accolades was the sculpture’s depiction of three different emotional states across its three figures: pain, death, and fear, or alternatively, death, fear, and compassion.

Renaissance thinkers noted that the marble seemed to pulse with genuine emotions. The father’s anguished cry and the sheer terror of his dying sons felt both visible and almost audible.

They were also intrigued by Plinio’s phrase “ex uno lapide” – from a single stone – interpreting it as a challenge to carve an entire sculpture from a single marble block. The David by Michelangelo, now in Florence’s Galleria dell’Accademia, is the most renowned result of this inspiration, the Ratto delle Sabine by Giambologna della Loggia dei Lanzi and Bernini’s equestrian statue of Luigi XIV at Versailles are also in this lineage. We now understand that the Laocoonte was actually crafted from multiple pieces so expertly joined they appear as one block. This suggests that Plinio’s words might be metaphorical, an interpretation supported by some modern critics.

Before we consider the art historians’ perspectives, it’s useful to mention another event that underscores the Laocoonte‘s impact on 16th century connoisseurs.

The rush to replicate the Laocoonte led to a vibrant cultural discourse, marked by both enthusiasm and fierce debates. The most notorious is the marble copy by Florentine sculptor Baccio Bandinelli, created between 1520 and 1523 and displayed at the Galleria degli Uffizi. Commissioned by Pope Leone X de’ Medici as a diplomatic gift to French King Francis I of Valois, the sculpture, however, never made it to its intended recipient. After Leone X’s death in 1521, his successor, Clemente VII, decided to keep Bandinelli’s work, placing it in the Palazzo Medici in Via Larga, in Florence. Bandinelli had made some alterations to the original, reconstructing the missing arms of the priest and his sons and making other adjustments to the child on the right of the observer.

Giorgio Vasari notes in his Vite that this work brought great fame to Bandinelli, yet it also attracted biting critiques, such as from Benvenuto Cellini who scornfully referred to Bandinelli in Rime as “envious, greedy, and no more than a stonecutter.” This was not just an art dispute but indicative of the intense rivalry between Rome and Florence at the time.

Laocoonte: a masterpiece in debate – copy or original?

It’s quite rare to encounter a classical sculpture that has garnered – and continues to attract – the level of acclaim that the Laocoonte group has since it was unearthed. The origins and creation of this work are shrouded in debate, making it just as challenging to decipher. Scholars have extensively debated the Laocoonte‘s meaning and provenance, yet there’s no consensus.

One school of thought posits that the Laocoonte is a marble copy of a lost Greek bronze original. Another camp views the marble group as a unique and original piece, inspired by earlier and concurrent artistic styles, but not a copy of any previous work.

It’s neither possible nor particularly constructive to rehash the detailed arguments of each side here, nor is it our role to adjudicate the most persuasive theory.

However, a brief overview of each stance can shed light on the issue’s complexity, inviting readers to delve further and reach their own informed conclusions.

The Laocoonte as a copy

Bernard Andreae is a notable proponent of the copy theory. He suggests that the Laocoonte is a marble reproduction from Tiberio’s era, based on a bronze original created in Pergamon around 140 BC. This original was intended as a political statement. During 141-139 BC, Scipione Emiliano was on a diplomatic mission to major Eastern states, including Pergamon, which was seen as the successor of ancient Troy and was governed by King Attalus II. The sculpture’s commission aimed to remind Romans and Pergamenes of their shared heritage, fostering reconciliation and averting the fate that befell Corinth and Carthage — both destroyed by Rome in 146 BC.

The bronze was likely used by Rhodian sculptors to depict the priest’s doomed effort to prevent the wooden horse’s entry, symbolizing Troy’s inevitable fall, Aeneas’s escape, and Rome’s subsequent rise, the latter being the heir to the storied city of Ilium. As Andreae points out, the sculptural narrative ties the fall of Troy to Rome’s founding, indirectly honoring Aeneas, the progenitor of the Romans and the gens Iulia, to which Tiberio (also associated with the Sperlonga statues) belonged by adoption. The sculpture is believed to have passed from Tiberio to Tito, where Plinio mentions it among the artworks in the latter’s estate.

The Laocoonte as an original

Salvatore Settis offers a counterargument. In his book Laocoonte. Fama e Stile (1999, Donzelli Editore), Settis reevaluates the sources, opposing Andreae’s viewpoint.

Starting with Plinio’s account – which explicitly names the three artists as summi artificies (master artists) rather than mere copyists – and considering the context in which Agesandro, Polidoro, and Atenodoro worked, Settis disputes the notion of the Laocoonte being a mere copy.

This counter-thesis challenges the assumption that the two Laocoonte (the supposed bronze original and the marble version) had to be politically motivated.

This theory is at odds with what we understand about Roman domestic decorations. Vitruvio tells us that depictions of Greek gods, mythological tales, Ulisse’s adventures, and the Trojan wars were commonplace in Roman homes, serving as status symbols for a specific socio-cultural elite. Such representations did not require a military or biographical rationale. By interpreting the Laocoonte – and other mythological tales – in a strictly political light, one strips the myth of its own inherent power, a power that was recognized and embraced in the society of that time. Myths were rich with symbolism and moral lessons, reflecting the beliefs, values, and aspirations of ancient culture. They served as educational, religious, and cultural instruments, strengthening social unity and collective identity.

Are you interested in articles like this?

Sign up for the newsletter to receive updates and insights from BeCulture!

The restorations and the arm controversy

When the Laocoonte was unearthed, it was remarkably well-preserved. Missing were only the priest’s arm, the arm of the younger son, the right-hand fingers of the elder son, and a few other minor elements.

Restoration work to replace the absent pieces began promptly and has spanned centuries. Laocoonte‘s arm, in particular, has sparked varied hypotheses and artistic interpretations, with some envisioning it reaching skyward and others picturing it bent and wrapped in serpentine coils.

Baccio Bandinelli was the first to intervene, fashioning a temporary wax arm to aid in creating his own replica. Later, around 1532-33, Giovanni Angelo Montorsoli, Michelangelo’s protégé, was tasked by Clemente VII with restoring the Belvedere sculptures, including the Apollo and Laocoonte.

A marble arm, unfinished and bent backward, believed to be Michelangelo’s work, appeared in 1720 but was never attached. The sons’ arms were added between 1712 and 1756 by the sculptor Agostino Cornacchioni from Pistoia. However, the most famed restoration is Filippo Magi’s in 1957, notable also for its association with a fortunate yet enigmatic discovery. It was then that the Laocoonte‘s original arm, fortuitously found by Ludwig Pollack in 1905 in an unnamed Roman stonecutter’s shop, was reinstated.

Save for a brief sojourn to Paris (1798 – 1815) due to the seizures by Napoleone (which also involved Castel Sant’Angelo), the Laocoonte has been kept in the Vaticano, where it remains on display. It has continuously captivated viewers, inspiring numerous reproductions, including irreverent renditions. A little-known fact is that in the mid-16th century, the engraver Niccolò Boldrini crafted a satirical version of the Laocoonte on a design by Tiziano. In this woodcut, the father and sons are humorously portrayed as monkeys, entangled in snakes’ coils. The intent behind this whimsical image remains a mystery, yet it underscores the Laocoonte‘s fame; to be parodied in such a way, it had to be widely recognized and unmistakably iconic – a status that the Laocoonte has consistently maintained.