Not everyone knows that Florence holds the world’s largest collection of Raffaello‘s paintings. This distinction was already recognized in the latter half of the 18th century when Raffaello’s Florentine works were among the primary attractions for visitors to the Tuscan capital, alongside other masterpieces like the Medici Venere and the Venere di Urbino by Tiziano.

As noted in 1779 by Bencivenni Pelli, the then director of the Galleria degli Uffizi, the Grand Duke of Tuscany boasted the most extensive collection of Raffaello’s paintings. Since then, the Uffizi and Palazzo Pitti have become essential destinations for those eager to explore this invaluable legacy.

Raffaello’s time in Florence

Seeking to witness the celebrated works of Leonardo and Michelangelo firsthand and driven by his “everlasting love for the excellence of art” (as Vasari recounts), Raffaello spent four years in Florence, from 1504 to 1508, across several visits.

The city’s affluent and cultured merchants played a crucial role in raising his profile, offering protection and securing numerous commissions.

In 1508, Raffaello relocated to Rome, where his compatriot and relative Donato Bramante, a painter and architect, was already making significant efforts to introduce Raffaello at the court of Pope Giulio II. Vasari mentions that Bramante advocated for Raffaello to serve as a judge in the competition to create the best large-scale wax model of the newly discovered Laocoonte sculpture.

In Rome, under the patronage of the papacy and local nobility, Raffaello’s talent and reputation reached new heights.

Today, Florence not only showcases works from his Tuscan period but also pieces acquired during his Roman years. A tour of the city’s principal museums provides a comprehensive view of the master from Urbino’s artistic development, a successor to 15th century Humanism and an exemplary exponent of the reinvigorated classical tradition.

Works of Raffaello at the Uffizi

The Galleria degli Uffizi is home to some of Raffaello’s masterpieces including Madonna del Cardellino, Ritratto di Elisabetta Gonzaga, San Giovannino, Ritratti di Agnolo e Maddalena Doni, Ritratto da Guidubaldo da Montefeltro, along with a selection of his preparatory drawings in the Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe. To give readers contextual information without spoiling the delight of an actual visit, we delve into a few of these works with a more thorough interpretation.

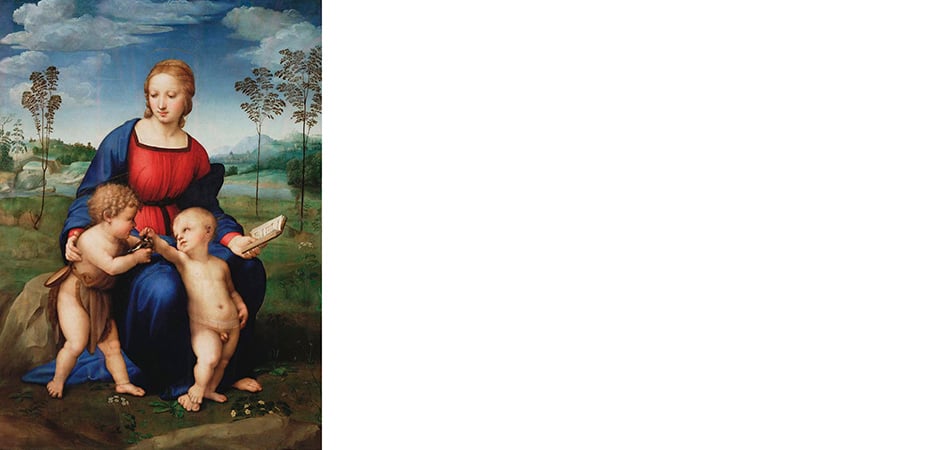

Madonna del Cardellino

Hailing from his early period in Florence, the Madonna col Bambino e San Giovannino is famously known as the Madonna del Cardellino, named for its depiction: the Virgin Maria seated outdoors, a holy text in her left hand, and the Infant Gesù Bambino on her lap, tenderly touching a goldfinch brought by an infant San Giovanni.

The panel shows influences from Perugino, the Florentine masters, and Raffaello’s studies on natural proportions. Its pyramidal composition echoes the lost Leonardo cartoon of the Madonna col Bambino e Sant’Anna and the Madonna col Bambino di Bruges by Michelangelo.

Yet the outcome is distinctively original and praiseworthy. By the mid-19th century, the Madonna del Cardellino was among the most replicated of Raffaello’s works in the Galleria degli Uffizi, alongside his Autoritratto and La Fornarina(currently in Palazzo Barberini, in Rome).

It’s a work embodying idealized beauty and dynamism, with layers of devotional symbolism like the goldfinch, representing Christ’s sacrifice, and was almost lost forever.

Commissioned for Lorenzo Nasi’s wedding in 1506, the panel was shattered in the 1547 collapse of the merchant’s home. Remarkably, its seventeen pieces were salvaged and likely restored by Michele di Ridolfo del Ghirlandaio.

Ritratti di Agnolo e Maddalena Doni

Agnolo Doni, a prominent merchant associated with the Wool Guild and a significant figure in Florentine patronage, was also an avid art collector, including precious items and ancient gems. He is linked to Michelangelo’s famous Tondo Doni, situated near Raffaello’s paired portrait. This double portrait, initially a diptych, was commissioned for his marriage to Maddalena di Giovanni Strozzi, who belonged to a lesser branch of the Medici family.

Both figures are painted on the front of two panels whose backsides instead feature monochrome representations of two consecutive episodes from Metamorfosi by Ovidio: the Diluvio degli Dei (on the back of Agnolo’s portrait) and the rinascita dell’umanità through Deucalion and Pyrrha (on the back of Maddalena’s), made by a pupil of Raffaello. Critics have interpreted this choice as a message of good fortune for the married couple.

The two are immortalized from the waist up, set against a shared landscape backdrop, demarcated only by the balustrade where Agnolo casually rests his arm. X-ray studies uncovered alterations in Maddalena’s image, which was initially framed within a Flemish-style domestic interior, later altered to its present setting. Given that Agnolo’s portrait does not show similar changes, Maddalena’s is considered slightly earlier.

Once more, Leonardo’s influence is unmistakable: the integration of figures and landscape, the torsos’ subtle non-frontal orientation, and the compositional structure recall the Gioconda, likely studied by Raffaello in Florence around late 1504. Yet, absent is Leonardo’s sfumato, in its place is a sharp, detailed rendering of forms, colors, and embellishments, like the attire and jewels adorning Maddalena.

Particularly notable is the unicorn-shaped pendant – only discernible upon close inspection – featuring an emerald, a ruby, and a sapphire, with a substantial baroque pearl dangling below. These elements are rich with metaphorical significance, implying good fortune: the mythical unicorn symbolizes chastity; the emerald is traditionally thought to possess healing qualities; the ruby a beacon of bodily strength and prosperity; the sapphire signifies purity; and the pearl, commonly gifted to brides, hints at virginity.

Works of Raffaello at Palazzo Pitti

Palazzo Pitti, especially the Galleria Palatina, is the residence of Raffaello’s masterpieces such as La Velata, Madonna della seggiola, Madonna del Granduca, Ritratto di giovane con pomo, Ritratto del cardinale Bibbiena, Ritratto di Leone X, Ritratto di Tommaso Inghirami, Visione di Ezechiele, Autoritratto, Madonna del Baldacchino, Madonna dell’Impannata, and the portrait of a pregnant woman known as La gravida.

La Velata

A quintessential work housed within the Galleria Palatina and a signature piece of Raffaello’s, La Velata was crafted after his relocation to Rome. Its precise date of creation, however, remains a matter of scholarly debate.

The painting captures a young woman against an indistinct backdrop, her upper body turned three-quarters towards the viewer, her right hand elegantly resting on her chest, her left hand just in view. A sheer white veil drapes over her hair, accentuating a pendant that boasts a ruby and a pearl, creating a delicate frame around her face. Her identity has been shrouded in mystery, with Vasari mentioning that she was the beloved whom Raffaello cherished until his last breath. Some suggest that she shares the countenance of La Fornarina, said to be Margherita Luti, the daughter of a Sienese baker and Raffaello’s muse. Yet, the debate persists, as others argue against this, pointing to the luxurious attire and jeweled necklace as attributes unfitting for a woman of La Fornarina’s modest origins.

Regardless of her identity, the foregrounded sleeve emerges as a focal point in the artwork. In it, we see the zenith of Raffaello’s artistic expression: the fabric’s texture, its voluminous shape, and the interplay of light and shadow are rendered with exquisite detail. The subject’s poised stance emphasizes the garment’s elegance, matched by the painting’s expansive composition that stretches to the canvas’s borders. X-ray examinations have revealed Raffaello’s continued refinements to the sleeve, resulting in the version now immortalized on the canvas.

La Velata also epitomizes the grace and virtue of femininity, virtues extolled by Baldassare Castiglione. The right hand’s open gesture over the heart signifies modesty and fidelity, while the blush of her cheeks, a wisp of hair across her brow, and her spirited eyes capture the essence of youthful beauty.

A final note of interest: the painting’s frame is not from Raffaello’s era but is a mid-17th century addition. Its ornate design, known globally as the cornice Pitti, is distinctively Florentine, featuring a unique assemblage of winged bat masks, foliage, and other whimsical motifs that cleverly conceal the frame’s angles.

Moreover, the painting’s presentation is notably distinctive. Rather than being hung by nails, it is affixed to pivots (a term known as bilicatura), allowing it to tilt vertically like a window sash. This 19th century innovation enables the artwork to be adjusted to the light, ensuring that it can be seen – and replicated – in the best conditions throughout the day.

Madonna della seggiola

The Madonna col Bambino e San Giovannino, also known as the Madonna della seggiola, is steeped in fascinating legends and is widely regarded as one of Raffaello’s most significant works.

Created around 1512, possibly outside Florence, its patron remains a mystery. By the late 16th century, the painting had made its way to Florence, evidenced by its successive placements in the Tribuna degli Uffizi, Palazzo Pitti, and, during Ferdinando Maria de’ Medici’s principality, in the Grand Prince’s bedroom.

This painting is a striking example of the tondo format, beloved in Florence, which Raffaello has uniquely adapted. Instead of merely fitting the figures within the circular frame, he arranges them to resonate with its shape, creating a harmonious composition.

In the artwork, we see the Madonna seated on a simple household chair, tenderly holding the Bambino, supported by her gently raised leg. Both figures engage the viewer while a devout Young San Giovannino looks on from the background. The painting derives its name from the prominently depicted chair, which also symbolizes the close bond between mother and child.

Raffaello’s inspiration is traced back to Madonna col Bambino by Donatello (the Madonna Dudley, now at the Victoria & Albert Museum of London), which was once part of the collection of a Florentine merchant, Piero del Pugliese, and later the Medici’s. This earlier work shares the theme of the Madonna’s inclined head and raised leg.

Raffaello’s Madonna cleverly weaves together influences from other renowned artists: the delicate poses reminiscent of Perugino, the powerful physical forms that echo Michelangelo (particularly in the Child’s elbow, which seems to almost protrude from the painting), and the vibrant color schemes found in Fra Bartolomeo’s works. What makes this painting truly stand out is its blend of divine solemnity with the intimate, everyday moments of human life. This balance of the sacred and the personal has cemented the Madonna della seggiola as a beloved piece of Raffaello’s oeuvre throughout history.

Ritratto di Leone X

Another chair marks the final stop on our exploration of Raffaello’s works in Florence. This piece features Pope Leone X, from the Medici family and successor to Giulio II, seated in a chair. The portrait includes his cousins, Cardinals Giulio de’ Medici (the future Pope Clemente VII) and Luigi de’ Rossi. The Opificio delle Pietre Dure in Florence meticulously restored it, and after a stint in Rome for an exhibition honoring the quincentennial of the artist’s death, it has returned to Palazzo Pitti.

The painting’s setting is austere and dignified, possibly a room in the Vatican library. It shows the three churchmen in reflective and solemn attitudes. Pope Leone X is depicted at a reading desk, magnifying glass in hand – a nod to his known myopia – as he appears to peruse a lavish, thick Bible that today resides in Berlin’s Kupferstichkabinett. A detailed bell on the table, reminiscent of ancient decorations Raffaello would have seen in Rome, and the standing cardinals flanking the Pope – Cardinal Giulio de’ Medici on the right and Cardinal Luigi de’ Rossi on the left – complete the scene. While initially thought to be later additions, scholars now agree that Raffaello himself painted the entire scene. Yet the circumstances and intended meaning behind this work still spark curiosity.

Are you interested in articles like this?

Sign up for the newsletter to receive updates and insights from BeCulture!

The painting’s origins are linked to the Italian wedding of the dukes of Urbino – specifically, Lorenzo, the Pope’s nephew, and Madeleine de la Tour d’Auvergne, the French King Francis I’s niece. This high-profile marriage solidified the Medici’s alliance with French royalty and was a cause for grand celebration.

Unable to attend the wedding banquet, the Pope sent his freshly painted portrait to Florence in 1518. It was displayed prominently at the wedding table, where it garnered widespread admiration for its exceptional craftsmanship.

The naturalism Raffaello achieved, lauded by contemporaries like Vasari, is evident in the lifelike representation of the figures. Raffaello does not gloss over even the Pope’s less graceful features, which are balanced by the opulence of the garments and the richness of the surroundings and artifacts. The painting’s vivid depiction of textures and materials – like satin, damask, silk, and shiny metals – reflects Raffaello’s delight in beauty and sophistication, an element also present in the Velata portrait.

Federico Zuccari’s 1607 work Idea dei pittori, scultori e architetti recounts an amusing story affirming the portrait’s realism. He tells of Bishop Baldassarre Turini da Pescia, who mistook the painting for the Pope himself and approached it to have a document signed.

Raffaello’s influence has seen highs and lows, with movements like the 19th century Pre-Raphaelites in England critiquing his style. Nonetheless, his impact on Renaissance art is unquestioned.

In the late 1600s, Ferdinando Maria de’ Medici compared Parmigianino’s Madonna dal collo lungo to Raffaello’s work, describing it as ‘drawn by Raffaello, finished with spirit, without struggle, and colored to perfection.’ This comment reflects the enduring admiration for Raffaello nearly two centuries after his death.

His artistic legacy, still prominent in Florence and around the world, leaves us with a poignant sense of what could have been. Raffaello’s premature death at 37 cut short a life of prodigious creativity, leaving us to wonder at the masterpieces that might have been.