Under the right arch of the monumental open-air museum that is the Loggia dei Lanzi in Florence stands a sculptural group of unparalleled dynamism and expressive intensity. Created in marble in 1582, the Ratto delle Sabine by Giambologna still amazes today with its colossal dimensions and bold composition: three nude bodies intertwined in a scene filled with violence and sensuality.

An eloquent work born from the ingenuity and ambition of one of the protagonists of Mannerism – let’s unveil its history and ambition together.

Subject and iconography

The Ratto delle Sabine (also known as Ratto della Sabina), depicts the kidnapping of a young woman by a strong, young man. The woman, naked and defenseless, struggles to escape his grasp, her lips parted and her face frozen in an expression of silent despair. At the couple’s feet, another older male figure watches the event in anguish, his body overshadowed by the assailant and his arm raised in a futile defensive gesture.

According to legend, the ancient founders of Rome abducted women from the neighboring Sabini people to make them their wives. Giambologna’s work is thought to represent this episode, but this is speculative because, according to sources, the title was assigned only when the work was nearly complete.

It appears that the author and art critic Raffaello Borghini suggested the title during a visit to the artist’s workshop. Before then, the group lacked a defined theme (it was a scene of an abduction, but not any specific one), and even Francesco I de’ Medici – who purchased it – had questioned the identity of the subject and its placement.

In a letter to his patron Ottavio Farnese, Duke of Parma, Giambologna writes that his bronze model of the Ratto (1579, Naples, Museo di Capodimonte) was chosen “to give scope to the wisdom and study of art”. In other words, it was a test of skill and technical virtuosity. We can thus imagine that the same motives drove the artist to create the subsequent marble work: without any commissioners, Giambologna executed it with the sole intent of matching and surpassing the undisputed master of this art until then – Michelangelo.

The comparison with Michelangelo

Giambologna was born in 1529 in Douai, in the Duchy of Flanders. At just twenty years old, he embarked on a formative journey to Italy, going to Rome to study classical sculptures and especially the works of his idol, Michelangelo Buonarroti.

It is even said that during his stay in Rome, the two met. Giambologna had gone to the then eighty-year-old Michelangelo to show him a wax model on which he had worked diligently. Upon seeing it, the Tuscan – famous for his brusque manners – took it, crushed it, and remade it, improving it. Then he dismissed the young Flemish artist with these words: “Now go first to learn how to sketch, and then to finish”. A likely apocryphal story, perhaps invented, but one that nonetheless testifies to Giambologna’s desire to excel. It might also explain why, of all his creations, numerous models have come down to us but no preparatory drawings – had he learned the lesson to the point of renouncing any sketches on paper to practice directly with the material?

However, after two years Giambologna moved to Florence, where he came into contact with the powerful Medici family and the lively circle of artists in the city.

It was here that, a few years later, he had the opportunity to confront the admired master once again.

Fate would have it that in 1560 a competition was announced for the creation of a statue of Nettuno intended to decorate the new fountain in Piazza della Signoria, placed right next to the David by Michelangelo. An irresistible opportunity: Giambologna participated, as did Benvenuto Cellini, Vincenzo Danti, and Bartolomeo Ammannati. Unfortunately for him, Ammannati won the project, creating the sculpture of the so-called “Biancone”, as it was caustically called by the Florentines of the time. Giambologna’s model, praised for its qualities, was probably reused for the figure of Oceano in the fountain of the Giardino di Boboli, now housed in the Museo Nazionale del Bargello.

But for Giambologna, the ideal challenge continued, and when he received the commission to create Sansone che atterra Filisteo (1561–62, London, Victoria & Albert Museum), he once again turned his gaze to Michelangelo. Buonarroti had created a similar subject, known today only through numerous sketches, as well as a series of wrestlers made for the tomb of Pope Giulio II.

In one of these sketches, preserved at the Bargello in Florence, Michelangelo had introduced a third character – a man lying down, perhaps dead, barely visible in the background. This variation, seemingly marginal, becomes the key to understanding the innovation brought about by the Ratto delle Sabine, which takes up and evolves Michelangelo’s scheme.

Sources of inspiration and stylistic achievements of the Ratto delle Sabine by Giambologna

The Ratto delle Sabine is the first sculptural group not to have a privileged point of view – a single front. To fully understand and appreciate it, the visitor is compelled to walk around it, discovering the multiple intertwining elements of its complex composition. Daring not only for its height (over 4 meters) but also for its weight, ensuring the stability of such a marble work without compromising its audacious upward thrust is no trivial matter. Giambologna therefore added the bearded man at the base, absent in earlier wax models (now at the V&A in London) and in the bronze version (but already present in the life-size model displayed at the Galleria dell’Accademia in Florence).

This choice was dictated by necessity but also by the desire to surpass his imposing predecessor. Unlike Michelangelo’s flattened figure, Giambologna’s man rises from the ground, is alive, and takes part in the scene – a figure that changes the game. From then on, the Ratto embodies the highest expression of Mannerism and its achievements: the pyramidal arrangement, the serpentine figure of bodies twisting spirally upon themselves, and the multiplication of movement in all three figures.

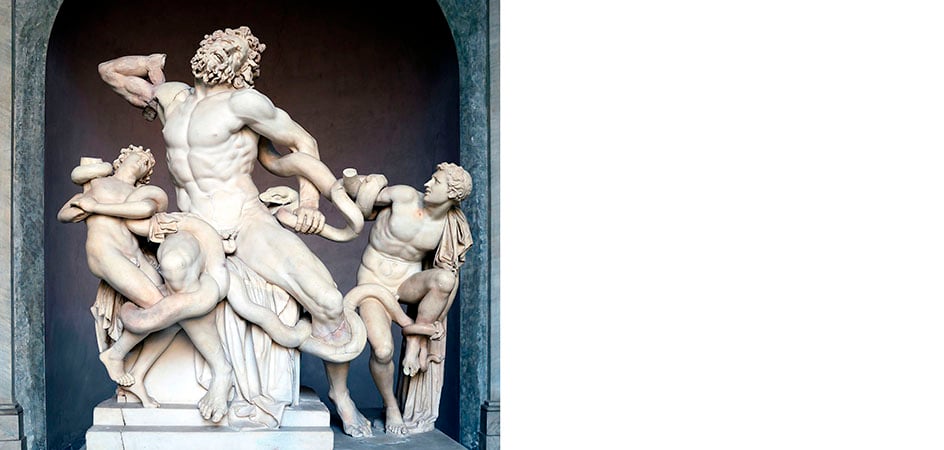

But Michelangelo was not the only source of inspiration for this Mannerist masterpiece. Among others was the Toro Farnese, a marble copy of a Greek original unearthed in Rome some time earlier (3rd century AD, Naples, Museo Archeologico Nazionale). Celebrated by painter Federico Zuccari (1539–1609) as “the most remarkable and wonderful work that came out of the chisel of the ancients”, along with the Laocoonte, it likely did not escape Giambologna’s attention during his stay in Rome. The man who seizes the Sabina closely mirrors the pose of the young man subduing the bull, except for the arms, which are raised to amplify the dramatic force of the abduction.

Are you interested in articles like this?

Sign up for the newsletter to receive updates and insights from BeCulture!

On January 14, 1583, the Ratto delle Sabine, after replacing Giuditta e Oloferne by Donatello in the Loggia dei Lanzi, was dramatically unveiled and presented to the public.

The long-desired confrontation with Michelangelo and his David had finally taken place. “But what was notable”, the sources report, “was that among so many people who saw [the sculptures of the Ratto], none found any fault with them in any part – a rare occurrence in Florence”.

Not even the Florentines – well-known for their critical spirit – had anything to complain about regarding the work, which since then has reminded visitors of the greatness of Jean de Boulogne, known as Giambologna.