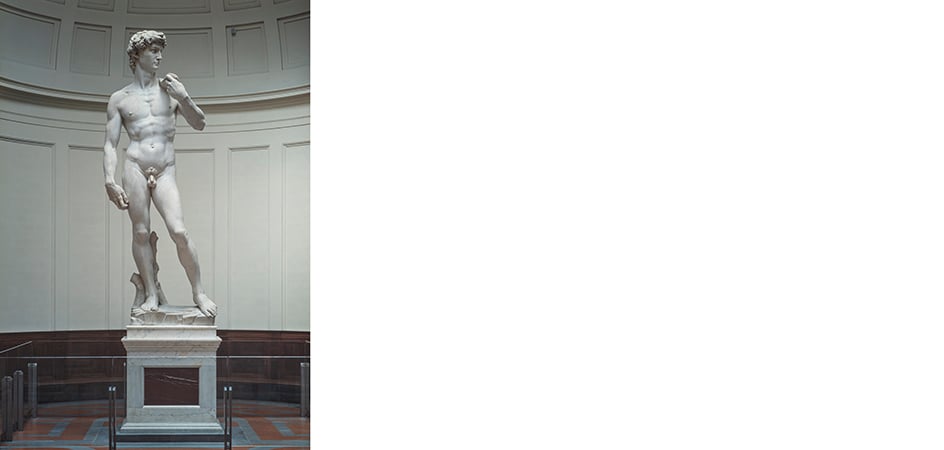

David, an icon of Italian art, embodies the spirit of an entire era and continues to fascinate millions of visitors worldwide.

Over the centuries, many words have been used to describe it, but perhaps the best are those of Vasari, who wrote: “And truly this work has silenced all modern and ancient statues, whether Greek or Latin […]. For in it are contours of beautiful legs and divine swiftness of hips; no such sweet posture nor grace comparable to this has ever been seen, nor feet, nor hands, nor head that in every member from the goodness of craftsmanship and parity, nor in design so greatly agrees”.

With this introduction, let’s delve into the history and analysis of Buonarroti’s timeless masterpiece.

The biblical episode

The subject, depicted by Michelangelo and others before him, comes from one of the most thrilling episodes in the Bible: the battle between King Saul’s Israeli army and the Philistines.

At the decisive encounter, Goliath – “a giant six cubits and a span tall, […] protected by a scaled armor weighing five thousand shekels of bronze” (1 Samuel 17) – challenges the Israeli army to fight him.

A young and courageous shepherd, inexperienced in the art of war, David, steps forward. Armed only with a staff, a sling, and five stones, David confronts Goliath with confidence, guided by the strength of God, who had secretly chosen him as the next king of Israel.

After an exchange of words, the duel is quickly resolved: Goliath does not have time to draw his sword before the young hero has already reached for his sling to hurl a stone that embeds in the giant’s forehead, felling him. David does not miss the opportunity and finishes the Philistine by cutting his throat with his own sword.

It is precisely this image of David victorious with the enemy’s head at his feet that the Florentines were accustomed to when Michelangelo, in 1501, accepted the commission to sculpt his version of the hero. A version that would revolutionize and forever change the representation of the young biblical king.

Michelangelo’s version: analysis of David

David’s virtues, his pride and invincibility had long been symbolically interpreted by Florentine artists, foremost among them Donatello, who authored two David. The first, in marble, around 1412-1416, and the other, around 1440 and the first nude in Renaissance bronze. Both works are now housed in the Museo Nazionale del Bargello in Florence, where a similar sculpture by Andrea Verrocchio from 1472 to 1475 is also found. In all, although different in style and composition, the hero is depicted post-combat, with Goliath’s decapitated head beneath him.

Michelangelo made a completely new choice. His David, as nude and even more so than Donatello’s (lacking even sandals and a cap), is captured in the moment before the confrontation. In his right hand, he holds a stone, his arm extended along his body; in his left, he holds the sling draped over his shoulder, in the chiasmo pattern often used by Buonarroti.

The face is focused and attentive, the entire figure conveys tension, the muscularity is poised to spring into action, the proud gaze fixed on the enemy. Everything is yet to be accomplished, no macabre trophy at his feet. His nudity is real but only apparent; this David needs no clothes or weapons to be a credible hero.

The dimensions are also important. The statue, standing 517 centimeters tall and weighing 5560 kilograms, was sculpted in over three years by the artist, not yet thirty years old, at the request of the Opera del Duomo.

The block of marble had initially been rough-hewn by Agostino di Duccio and Bernardo Rossellino, then abandoned as too difficult to work.

For a monthly salary of 6 gold florins (though the price of the statue would be raised to 400 ducats shortly thereafter), Michelangelo accepted the commission. Not only did he have to deal with complex material already partially damaged, but he also had to contend with a subject with illustrious predecessors and significant symbolic value for the city of Florence.

To succeed in his task, he referred to classical statuary seen in Rome – where he had stayed until a few months earlier – matching and even surpassing it in beauty and majesty. The surface of David is worked in every detail and perfectly smoothed, except for the base treated rustically. As Vasari wrote in his Vite commenting on the statue: “[…] whoever sees this, need not care to see any other work of sculpture made in our times or in others by any craftsman.”

The commissioners must have thought so the first time they saw it.

The placement: a history in stages

On January 25, 1504, a commission composed of the era’s leading artists (including Leonardo da Vinci, Sandro Botticelli, Filippino Lippi, il Perugino) convened to decide the best placement, as the cathedral’s spur initially hypothesized was considered unsuitable for such a masterpiece.

The resolution of May of the same year decreed that the most suitable place was instead Piazza della Signoria, in front of Palazzo Vecchio (the seat of city power), replacing the Giuditta by Donatello, which was moved to the Loggia dell’Orcagna. It is likely that Michelangelo worked on refining the work until September of the same year. During these months, an incident both humorous and indicative of the artist’s personality occurred. It seems that one day, the gonfaloniere Pier Soderini, looking up at the statue, criticized its nose, deemed too large. Armed with a chisel, Michelangelo, after hiding some marble dust in his hand, pretended to correct it, letting the dust fall down. An intervention that the gonfaloniere, completely unaware of the deceit, considered perfect!

On September 8, the colossus, emblem of the strength and independence of the Florentines, was unveiled to the citizens, leaving them amazed, and so the fame of its brilliant author grew unparalleled.

However, David‘s history is not without misadventures and events that have jeopardized its integrity.

In 1512, it was struck by lightning with serious consequences for the stability of the original base, now lost and replaced by a copy; while in 1527, during the tumults related to the expulsion of the Medici, it was vandalized: the left arm was shattered, reconstructed at the behest of Duke Cosimo in 1543. In the same years, during the censorious climate of the Counter-Reformation, the genitals were also covered with a metal vine placed at the hips of the statue.

Are you interested in articles like this?

Sign up for the newsletter to receive updates and insights from BeCulture!

It wasn’t until the 19th century that the idea of moving the statue to a more suitable location for its conservation began to be considered.

A matter raised by sculptor Lorenzo Bartolini in 1842 and continued publicly until 1872, when it was decided to move David inside the Galleria dell’Accademia. Even today at Casa Buonarroti (a must-visit for those wanting to see Michelangelo’s works in Florence) is preserved the model of the huge wooden rigging that the following year wrapped the giant and allowed its transfer – lasting a full 10 days – from the Piazza della Signoria to the Museo Nazionale del Bargello.

Yet David had to wait another 9 years enclosed in a crate before it could once again be admired in its new location: the time necessary for architect Emilio De Fabris to complete the grand Tribuna designed to host it. A setting conceived to enhance its formal characteristics: in this modern apse flooded with light, David stands alone.

The path itself imagined by the museum contributes to generating a visual and emotional crescendo: in the airy corridor leading to the Hall of the Colossus, i Prigioni, also by Michelangelo, a series of non-finite (not-finished) sculptures that anticipate, with their dynamic incompleteness, the spectacle of David. An engaging and totalizing experience we invite you to live in person.