Portraits have always aroused curiosity and interest in the viewer, who can attribute a face to a famous name or be confronted with unknown figures, fascinating for the mystery surrounding them. The commissioner, on the other hand, is driven by the desire to transmit their memory to posterity, and the portrait, sometimes idealized, in other cases truthful, is the most effective way. Depending on the point of view, the painted effigy is therefore a tool to transcend the present: an immersion in the past or a projection into the future.

Historically, portraits were the prerogative of the nobility until the Renaissance, when a new social class, the mercantile class, emerged, capable of commissioning works and portraits from the great artists of the time. This genre thus spread significantly. Of Raffaello, one of the most renowned artists, we have numerous testimonies today: 5 of his most famous portraits prove it.

1. Ritratto di Guidobaldo da Montefeltro e Elisabetta Gonzaga

We begin with a double portrait en pendant, that of Guidobaldo da Montefeltro and Elisabetta Gonzaga, located in the Uffizi. Critics have not always agreed on attributing the two panels to Raffaello, but today their authenticity is widely recognized. The frontal pose of the figures still reflects the Flemish influence and, for this reason, the paintings are dated between 1503 and 1504. Another work by Sanzio, the Ritratto di giovane con pomo (in the Galleria Palatina of Palazzo Pitti) from 1504 shows an evolution in the arrangement of the subject: no longer frontal but turned three-quarters, a setup that Raffaello will maintain from then on for almost all his portraits.

Guidobaldo da Montefeltro is depicted in a solemn attitude, dressed in black and gold, the colors of the house, with a dark shirt, richly decorated jacket, and a wide-brimmed hat. Behind him is a closed environment that opens onto a window framing a hilly landscape in the distance.

Elisabetta Gonzaga shares the same compositional setup, with the difference that the space behind her is completely open and illuminated by orange reflections absent in her husband’s effigy. The most striking feature of Gonzaga is her sumptuous dress, also black and gold, bordered by an inscription that scholars have not yet deciphered.

Another enigma is the jewel adorning the duchess’s forehead: a scorpion-shaped pendant containing a precious stone, probably a diamond. Among the various interpretations, it is worth remembering two. It was common practice to use scorpion venom or the dried animal itself for medicinal preparations: the scorpion would thus have an apotropaic function. A second interpretation instead relates it to the zodiac sign (although the duchess was born in February), often associated with prosperity and fertility: a symbol of good omen for the couple who could not have children.

Son of Federico da Montefeltro and Battista Sforza (portrayed a few years earlier by Piero della Francesca in the Uffizi diptych), Guidobaldo would be the third and last duke of Urbino of his dynasty. In the absence of direct heirs, the title and duchy would pass to Francesco Maria della Rovere, nephew of Julius II and adopted son of the couple. It is thought that he could be the young man with the apple depicted in the painting mentioned above.

2.The double Ritratto dei coniugi Doni

The rigidity of the diptych just described is overcome by Raffaello only a few years later with the double portrait of the Doni couple (in the Uffizi), made during his Florentine period. A crucial stay for the evolution of the artist’s knowledge and style.

No longer frontal, Agnolo Doni and Maddalena Strozzi are oriented three-quarters; no longer cut at the chest level, they show their shoulders, bust, and hands. An arrangement that was not new in portraiture of the time but testifies to Raffaello’s debt to Leonardo and his Gioconda. The artist from Urbino recalls – especially in the portrait of Maddalena Strozzi – the pose of the hands, the occupation of the pictorial space by the figure, and the relationship of the latter with the background. He adds a new note of realism, a frankness of gaze and expressions (barely perceptible in the Gonzaga portrait and here fully manifest), which will earn him important commissions afterward.

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. Here we are still in Florence, and Raffaello has been commissioned by Agnolo Doni, a wealthy merchant of the city, to portray him together with his wife, the noblewoman Maddalena Strozzi. The occasion could have been their wedding or, it is hypothesized, the birth of their firstborn (an event that could also be the reason for the commission of Tondo Doni by Michelangelo).

The paintings were thus made by Sanzio between 1504 and 1507 and are held together by a hinged frame that allows admiring the scenes depicted on their respective verso, created by a pupil of Raffaello: Deucalione e Pirra on the verso of Strozzi’s panel and the Diluvio dei Dei on that of Doni. Episodes taken from Metamorfosi by Ovidio, a message of good omen for the couple.

The precious stones set in the pendant worn by young Maddalena (just fifteen at the time of her marriage) are also allusive: virtues such as chastity, purity, and fidelity are indeed evoked by the emerald, ruby, sapphire, baroque pearl, and the golden unicorn that surmounts them. This mythical animal and Maddalena Strozzi are linked to another Raffaello portrait: the Dama con l’Unicorno (1504-1505) at the Galleria Borghese in Rome. Until 1935, the work appeared as a Santa Caterina with the spiked wheel (a typical iconographic motif), but the restoration of that year revealed the unicorn present under the wheel, which was then removed.

The Strozzi family resided in Florence in the Santa Maria Novella district, known as the Unicorn’s gonfalon: from this, part of the criticism concluded that the Lady with the unicorn was indeed young Maddalena, idealized in her features (blue eyes, blonde hair) to better embody the personification of chastity.

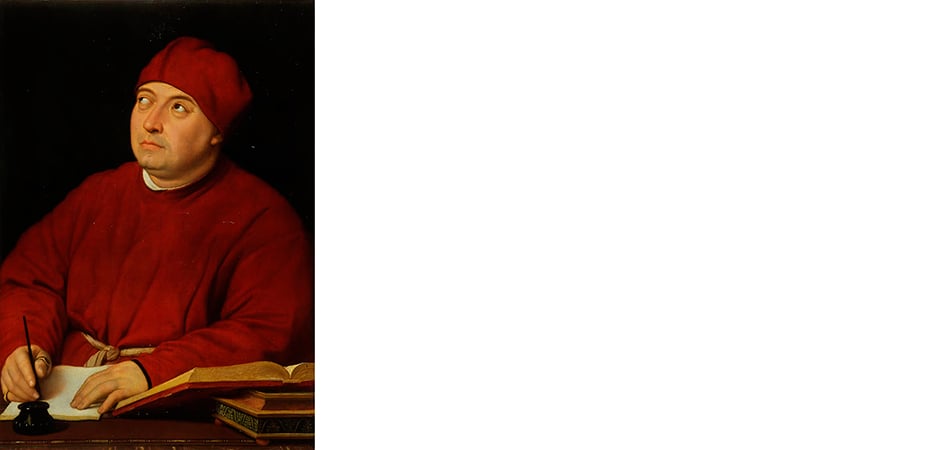

3. The Ritratto di Tommaso Inghirami called Fedra

On the other hand, the Ritratto di Tommaso Inghirami, which fits into Sanzio’s happy and prolific Roman season, seems not to be idealized at all.

Born in Volterra in 1470, Inghirami was a well-known and appreciated humanist, so much so that he was appointed prefect of the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana between 1510 and 1516, the year of his death. It is during this period that Raffaello’s panel, now in Palazzo Pitti, was made, where the prelate is portrayed against a dark background (originally a green curtain) while, dressed in red and sitting at the lectern, he looks upwards awaiting inspiration. A pose adopted since the Middle Ages in miniatures of evangelists engaged in writing the Holy Scriptures.

Inghirami, nicknamed Fedra for his theatrical interpretation of Seneca’s homonymous character, was also known for his pronounced strabismus. A detail that Raffaello does not fail to represent, though partially concealing it by adopting the side pose.

The painter’s sincerity also shines through in the complexion, marked by a not perfectly shaved beard, the full face, and plump hands: elements of realism that do not diminish the solemnity of the scene but contribute to its candid veracity.

4. La Velata and La Fornarina

It is believed that La Velata (1514, Galleria Palatina, Florence) and La Fornarina (1518-1520, Gallerie Nazionali Barberini Corsini, Rome) are portraits born out of a love affair between the painter and the subject. According to the interpretation inaugurated by Vasari, in both cases, it would indeed be Margherita Luti, the daughter of a baker from Trastevere, Raffaello’s lover, and muse.

We know that the artist from Urbino was far from indifferent to women, and according to the Arezzo biographer, he would have even died prematurely due to reasons related to his love affairs (today we can hypothesize that it was some venereal disease). We also know, from the same source, that Cardinal Bibbiena insisted heavily for the painter to marry a relative of his: something that did not happen, but which could justify the favorable relations that Raffaello had with Maria Dovizi, Bibbiena’s niece, perhaps intending to win the favor of the Roman nobility.

Aside from the background, what remains today are two splendid portraits of young women without a known commission. La Velata owes its name to the veil covering her head and shoulders, although the most striking element is certainly the sleeve of the dress in the foreground, masterfully described by Raffaello. The young woman’s face, slightly in shadow, with a gaze directed at the viewer and the gesture of her right hand at heart level, transmits unparalleled grace and reserve.On the other hand, a strong erotic charge emanates from LaFornarina, partly due to her partial nudity. She too brings a hand to her chest, while the other covers her pubis, in line with the model of the classical Venere pudica, echoed a few years later by the Venere by Tiziano. And it would indeed be a Venere, as confirmed by the bracelet with the author’s signature (“Raphael Urbinas”) as a sign of a love bond and, behind the woman, the myrtle bush – sacred to the goddess – and the quince branch, an emblem of fertility.

5. The Ritratto di Leone X tra i cardinali Giulio de’ Medici e Luigi de’ Rossi

Nobles, merchants, intellectuals, and churchmen, Raffaello received many commissions once he arrived in Rome. Among the most important is that of Pope Leone X, for whom he created one of the most acclaimed portraits of his entire production.

Executed in 1518 to be sent in place of the pope on the occasion of the marriage between his nephew Lorenzo de’ Medici, Duke of Urbino, and Madeleine de la Tour d’Auvergne, niece of King Francesco I of France, the painting portrays the Medici pope and two cardinals: Giulio de’ Medici, the future Pope Clemente VII, and Luigi de’ Rossi.

For a long time, it was believed that these two figures were added by others later, but recent restoration has confirmed the authenticity of the entire work.

A work dominated by the pope, who, with his corpulent and richly dressed figure, occupies the center of the composition. Seated at the reading table, he looks elsewhere while holding a gold-ornamented magnifying glass (used to correct his myopia) with one hand and approaching the illuminated book open in front of him. The volume has been identified as the precious Bible preserved at the Kupferstichkabinett in Berlin, a mid-14th century codex decorated by Cristoforo Orimina, one of the most famous miniaturists of the time.

As with Inghirami, Raffaello is not intimidated by the authority of the commissioner and portrays him with all his defects, including his ungainly features.

Are you interested in articles like this?

Sign up for the newsletter to receive updates and insights from BeCulture!

According to Vasari, the portrait caused such a stir that Alessandro de’ Medici, Duke of Florence, secretly commissioned an identical one from Andrea del Sarto because he wanted to give it to Federico II, Duke of Mantua. The copy was then sent to Mantua, passed off as an authentic Raffaello

Intending to display it, Federico II summons Andrea del Sarto and Giulio Romano. In the presence of the copy, Andrea del Sarto reveals the misdeed, but the other – surprisingly – denies it. Giulio Romano had seen the painting months before and declared its authenticity to the duke. To avoid losing credibility in the eyes of the Lord of Mantua, Giulio Romano denies Andrea del Sarto’s words and accuses him of lying, stating that he had worked on it himself with Raffaello: “How is it not true? Don’t I know that I recognize the strokes I worked on?” a lie that served to save face.

A comedy of errors demonstrating how Raffaello’s masterpieces have always been capable of generating noble or less noble feelings and behaviors, all proof of his greatness.

Portraits, as we know, tell stories and reveal – through an expression or the detail of a garment – the life, character, and ambitions of their protagonists, triggering a game of looks and emotions that goes far beyond the painted surface.