Museum visits often transport us through time as we stand captivated by the artwork, we inevitably engage in an exercise of interpretation. Deciphering the subjects and scenes, especially when it comes to saints, isn’t always straightforward.

The attributes, postures, and life events of these holy figures have grown distant from modern understanding, leaving us at times perplexed by the art’s message, which might strike us as peculiar or unconventional.

It’s ironic when you think about it – during the Middle Ages and beyond, saintly iconography was a standardized and widely understood visual language, serving as an instructional aid in religious teachings.

Mastering the art of identifying these key figures doesn’t just mean pinpointing the main theme of a painting; it’s about unlocking the symbolic narratives woven into the canvas.

This concise guide takes you through the tales and trademark belongings of some of the most frequently depicted saints, whose depictions continue to spark wonder and intrigue.

Sant’Anna

The veneration of Sant’Anna stretches far back in time, yet she was officially entered into the liturgical calendar in 1584. She is the mother of the Vergine Maria and frequently appears in early paintings as a venerable elderly figure clad in a green mantle, alongside the young Maria and Gioacchino, her spouse. Despite two decades of a barren union, an angel’s promise of a child rekindled hope for Gioacchino, who had withdrawn, believing himself to be under a divine curse.

One cannot speak of Sant’Anna artistic portrayals without highlighting the Sant’Anna Metterza by Masaccio and Masolino da Panicale, showcased in the Galleria degli Uffizi. This piece illustrates a threefold lineage: Anna as the mother of Maria and the forebearer of Gesù, a concept termed metterza in Tuscany, meaning mi è terza.Equally striking is her representation in Madonna dei Palafrenieri by Caravaggio, created nearly two hundred years later. Despite the passage of time, Anna’s depiction retains a profound solemnity and an air of enduring majesty.

Santa Caterina d’Alessandria

Santa Caterina d’Alessandria came from a lineage steeped in royalty, the progeny of Cyrene’s king. A devout Christian, she declined marriage to the pagan Emperor Maxentius. Unyielding in the face of persuasion, she not only stood her ground against philosophers and scholars sent to sway her convictions but also converted them to Christianity, leading to their execution by the emperor.

Caterina herself faced harsh imprisonment, starving but for sustenance provided by a heavenly dove. Her resilience was further tested by the breaking wheel, which miraculously shattered, saving her from that fate. Caterina was ultimately executed, and as the legend goes, milk, not blood, flowed from her neck.

In art, Caterina’s regal heritage is often symbolized by a crown, but the breaking wheel remains her most distinctive emblem. She is also portrayed holding the martyr’s palm, sometimes with the sword of her beheading, and bearing the ring symbolizing her spiritual union.

The 1474-1479 painting by Hans Memling, Madonna con Bambino in trono e quattro santi, preserved at the Memlingmuseum in Bruges, captures Caterina’s essence. Kneeling beside the Vergine, she is arrayed in rich garments with her symbolic sword and wheel resting at her feet. In contrast, Masolino da Panicale’s early 15th-century fresco Martirio di Santa Caterina in Chiesa di San Clemente in Rome presents a more modest depiction.

San Francesco d’Assisi

San Francesco d’Assisi’s story begins in 1181, in the Italian town of Assisi, where he was born into the wealth of his father, Pietro Bernardone, a prosperous textile merchant. Raised with the expectation of knighthood, Francesco’s life took a turn following a profound vision on his way to battle in Spoleto. At the age of 23, he made a life-altering decision to forsake his weapons and wealth, pursuing a stark life of conversion, penance, and poverty. His commitment led to the founding of the Ordine dei Frati Minori, an order that continues to honor his legacy.

The story of Francesco’s life has been captured extensively in art, especially in the works that memorialize him after his death in 1226. His rapid canonization, merely two years posthumously, is a testament to his enduring influence within the Christian faith.

The life and devotion to San Francesco are immortalized in frescoes by Giotto (1265-1337) in the Basilica di San Francesco in Assisi and the Cappella Bardi in Florence. These artworks frequently feature Francesco in his monastic robe, with a cross and the stigmata, the latter of which he received on monte della Verna shortly before his passing and which became his most distinctive iconographic symbol.

San Giovanni Evangelista e San Francesco d’Assisi by El Greco, an oil on canvas dating back to 1600, now part of the esteemed Uffizi collection, poignantly captures Francesco. The painting portrays him as emaciated, with a hand over his chest, drawing attention to the marks of his stigmata.

San Giovanni Battista

The narrative of San Giovanni Battista is chronicled in the Gospels and apocryphal texts. Born to Elisabetta, a relative of Maria, and Zaccaria, Giovanni born just before Cristo. He chose a reclusive life in the desert as a hermit, dedicating himself to the ascetic practice of preaching and performing baptisms along the Jordan River. It was there that he baptized Gesù, uttering the words: “Behold the Lamb of God”, a symbol that would become synonymous with his own depictions. His other distinctive iconography include animal skin garments, bearing a cross, and a scroll.

His life, marked by prophetic zeal, met a tragic end by decapitation, a request made by Salomé and granted by Erode. Salomé, the daughter of Erodiade (Erode lover and the wife of his brother), had earned the right to have any wish granted, which she expressed by asking for Giovanni’s head.

The Galleria degli Uffizi houses a rich tapestry of artworks that capture the essence of Giovanni Battista’s life. Madonna del Cardellino by Raffaello shows him as a child; Madonna con Bambino, San Giovanni Battista, Sant’Antonio abate, Santo Stefano e San Girolamo by Rosso Fiorentino depict his youth; and the mature Giovanni appears in the Battesimo di Cristo by Andrea del Verrocchio and Leonardo da Vinci.

Despite the different life stages, Giovanni Battista’s identity is consistently conveyed through enduring iconographic elements.

San Girolamo

San Girolamo stands out in the realm of saintly iconography. Born to an aristocratic Christian family in Aquileia, Girolamo was a scholar who traveled widely, immersing himself in the theological and exegetical discourse of his era. After taking monastic vows, he lived as a hermit in the desert from 353 to 358.

Girolamo’s scholarly pursuits led him to Rome, where he was tasked with translating the Bible from Greek and Hebrew into Latin, producing the esteemed Vulgata. Medieval belief held that Girolamo was a cardinal, serving the Pope in this scholarly endeavor, a notion reflected in his portrayal in art, complete with a cardinal’s red cloak and hat, as seen in the Sacra Famiglia con San Girolamo by Lorenzo Lotto. But Girolamo’s iconography doesn’t end there; it includes a stone for self-flagellation, a book or scroll signifying his scholarly revision, a skull symbolizing the futility of worldly matters, and a lion, which, as the Legenda Aurea has it, he healed and remained loyal to him at the Bethlehem monastery. Some artworks also feature an hourglass, a reminder of life’s fleeting nature.

The Tentazioni di San Girolamo by Giorgio Vasari an oil on panel painted in 1541 and now residing in the Galleria Palatina at the Palazzo Pitti, offers a comprehensive depiction of San Girolamo.

The saint is shown in a posture of penance, kneeling by a rock with the stone pressed to his chest, a loyal lion by his feet, and draped in a red cloak that cradles a cross, behind which books and a skull can be glimpsed. Mythological and allegorical figures, such as Venere, Cupido, and the personification of Gioco, hover in the background, symbolizing vanquished temptations.

San Lorenzo

San Lorenzo, who served as a deacon under Pope Sisto II during Valeriano’s rule, met a martyr’s fate in 258 for defying the imperial prefect by distributing the Church’s wealth to the impoverished. He is traditionally depicted with the dalmatic, a long Roman robe worn for liturgical purposes, the book of Psalms, and the gridiron upon which he endured his torture.

According to apocryphal tradition, while being punished, Lorenzo said to Valerian as he was being martyred: “I’m well done on this side, turn me over and eat me”.

This episode of gallows humor is captured in the form of a sculpture by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, which vividly showcases Lawrence writhing in agony upon the searing gridiron, his gaze heavenward.

Bernini’s dedication to depicting the saint’s anguish was so profound that, as his son Domenico’s biography recounts, the artist replicated the pain on his own skin, searing his leg against coals to accurately sketch the tormented expressions.

While Lorenzo is often portrayed in his final moments of martyrdom, art has also captured him in different contexts. A notable absence is the Natività con i santi Lorenzo e Francesco d’Assisi by Caravaggio, a masterpiece lost to theft in 1969 from the Oratorio di San Lorenzo in Palermo, leaving a void in the historical tapestry of Lorenzo’s representations.

Santa Lucia

Santa Lucia, whose story is marred by the brutal persecutions of Emperor Diocleziano against Christians, stood firm against the man she was pledged to marry, a decision that led to her martyrdom by beheading in 304. Her defiance was profound; she resisted being taken to a brothel, assaulted, or burned at the stake. Even as she conversed with the prefect, she was immovable, made exceedingly heavy by the Holy Spirit, not even several oxen could move her.

Santa Lucia davanti al Giudice by Lorenzo Lotto, on display at the Pinacoteca Nazionale of Jesi, captures this remarkable scene.

Santa Lucia is recognized not just for the palm of martyrdom and the sword or dagger of her execution but also for a unique attribute: her eyes carried on a plate. This portrayal, linked to her name’s connotation with light, has inspired tales of eye torture. One of the most acclaimed artworks of this resilient martyr is Santa Lucia by Francesco del Cossa, held at the National Gallery in Washington, where Santa Lucia is depicted holding her eyes with a grace as if cradling a sprig in bloom.

San Michele Arcangelo

Arcangelo Michele’s role as the celestial commander leading the angels in their cosmic battle against Satan is rooted in the visions of the Book of Revelation (Rev. 12, 7-8) and helps us understand his representation. His artistic depictions are grand and striking, often featuring him in resplendent, ornate armor – or in regal robes – engaged in combat with the forces of evil, symbolized by rebellious angels and the dragon, a representation of the devil, and in the act of weighing human souls.

Typically portrayed wielding a sword, Michele is also known for holding the scale that, in religious tradition, is used to weigh the souls of the departed, assessing their worthiness in the presence of God. This image of Michele is immortalized in artworks such as Bernardo Zenale’s painting from circa 1490, safeguarded within the Uffizi, and a later Russian icon, dating between 1725-1750, on display at the Museo delle Icone Russe in Palazzo Pitti.

Are you interested in articles like this?

Sign up for the newsletter to receive updates and insights from BeCulture!

San Sebastiano

San Sebastiano is commonly envisioned as the youthful Renaissance figure, bound to a post or tree, and pierced by arrows. Yet, this portrayal, while iconic, doesn’t align with the actual manner of his demise.

Sebastiano, a Gaulish soldier who served in Diocleziano’s army, embraced Christianity, and was sentenced to death for aiding imprisoned Christians. This courageous act led to his death sentence. Struck by arrows, he was taken for dead and abandoned, but was rescued by the widow Irene and recovered, only to return to the presence of Diocleziano. The emperor then ordered that he be clubbed to death and his body thrown into the Cloaca Massima, the largest sewer of Rome at the time. From there, a Christian retrieved his body and buried it in the catacombs.

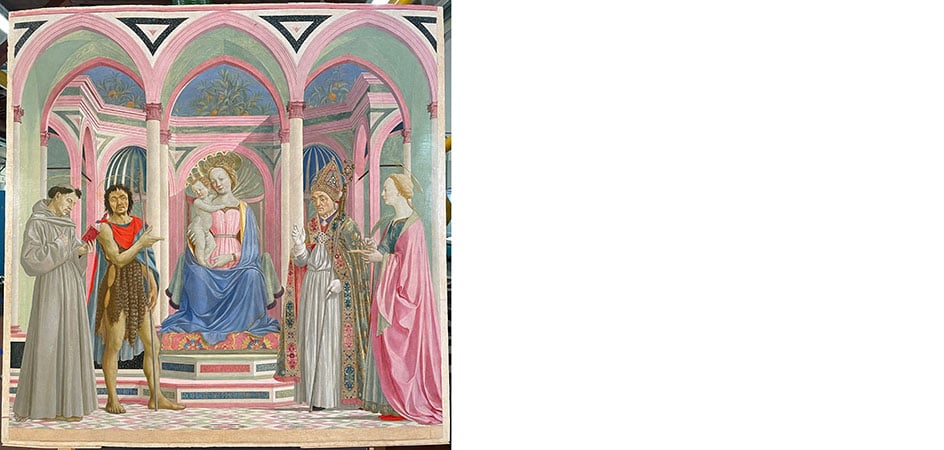

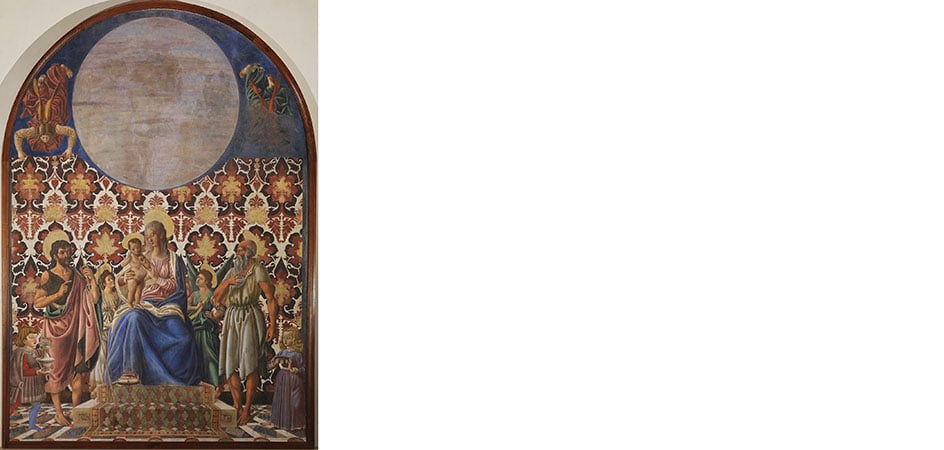

Beyond the arrows, the palm of martyrdom is another symbol frequently associated with Sebastiano. Antonello da Messina‘s depiction of the saint is particularly striking, a piece currently housed in the Gemäldegalerie in Dresden. Saints frequently appear in art, each with their unique story. Sometimes they’re part of choral scenes, blending into narratives around the Holy Family or private devotions. Identifying them without the aid of captions can be a rewarding challenge, sharpening memory and observation. It’s an engaging activity that can even draw children into the wonders of museum exploration. For instance, with the insights from this article, would you be able to recognize the saints in the fresco Madonna in trono by Andrea del Castagno displayed at the Uffizi or those in Madonna con bambino in trono by Domenico Veneziano, in the same gallery?