How is food depicted in art? And with what meanings? What stories does it tell?It is certainly not possible to exhaust such a rich subject in a single article, however, let’s try to retrace together the main representations of food in art, with, but not exclusive, attention to the Cinquecento. A period during which food increasingly emerges: allusive and subordinate to the main theme represented in the first half of the century, it then becomes the main subject, protagonist of genres and fashions destined to last a long time.

Food in religious, historical, and mythological scenes

Food appears in various forms and functions in the texts of the Old and New Testament, but also in mythology, literature, and history: all sources from which artists have always drawn inspiration to represent, according to codes and styles of their time, food and beverages.

Art, food and sacred history

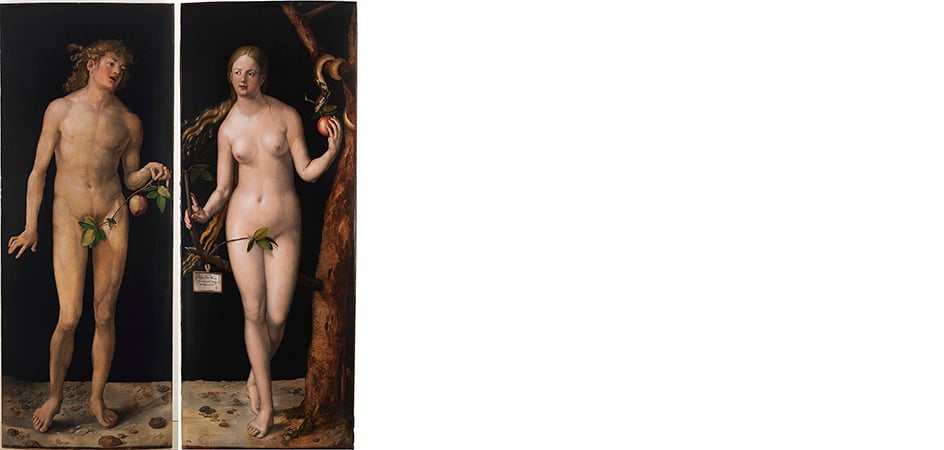

Let’s start from the Original Sin, a common subject in medieval and Renaissance art. The episode of Adam and Eve with the forbidden fruit of the tree of knowledge has also been depicted by Albrecht Dürer. In 1507 the German painter created two panels (now preserved at the Museo del Prado in Madrid) where the biblical progenitors appear naked, with apple twigs in hand. A botanical variety not explicitly mentioned by Genesis, but which has been interpreted by many northern painters based on the Latin word malum, used to indicate both the fruit and evil.

It is found, among others, also in the namesake oil on canvas by Tintoretto (Galleria dell’Accademia di Venezia) from the mid-16th century: here, Eve appears in the act of offering the apple to Adam who, with his back to the viewer, withdraws hesitantly.

Banquets and dinners are another rather frequent theme in sacred texts and, consequently, in past art, becoming occasions to also represent food.

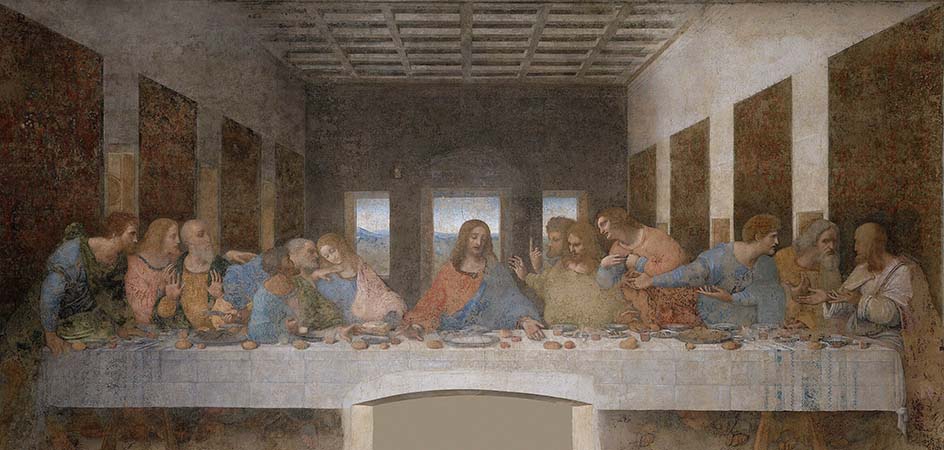

The most depicted feast is certainly the Ultima Cena, of which the marvelous fresco that Leonardo Da Vinci created in 1497 for the Dominican convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie, in Milan, is still preserved. Leonardo chooses the moment of revelation when Christ – at the center of the composition – declares he knows of the impending betrayal, causing dismay and fear among the Apostles. The table is set with glasses, plates, and knives. The dish served, along with the Eucharistic bread and wine, is not the Easter lamb but fish, an emblem of penance, probably in accordance with the Benedictine rule that prohibited the consumption of quadruped meat. However, there are also symbolic objects and gestures: the salt spilled next to Giuda’ elbow suggests a missed opportunity (that of spreading the word of the Messiah in the world); on the contrary, the full silver salt shakers near Giacomo minore and Matteo would have exactly the opposite value; finally, the knife held by Pietro behind Giuda anticipates the armed confrontation between the Apostolo and the assailants of the Messia in the Orto degli olivi.

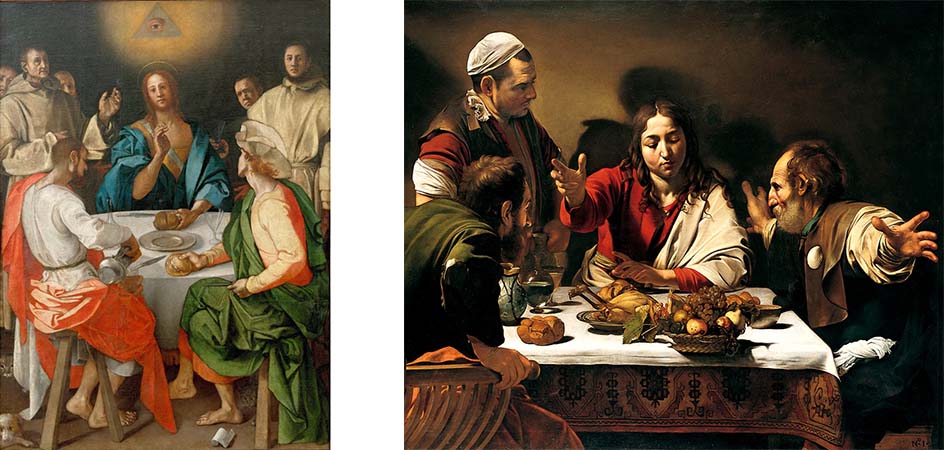

Explicit reference to the Cenacolo is the Cena in Emmaus, the place chosen by Cristo to show himself resurrected to two travelers by repeating the gestures of the Ultima Cena: he takes the bread, blesses it, breaks it, and distributes it among his unsuspecting companions, disappearing immediately after. In the namesake canvas from 1525 preserved at the Galleria degli Uffizi in Florence, Pontormo narrates the revelation in a composition centered around the figure of Christ. Bread and wine are the only foods present, but it is also interesting to note the metal plate that refers to the patena, the Eucharist plate, and the Renaissance custom of sharing the serving dish among all the diners.

It is impossible not to mention, speaking of such a subject, the Cena in Emmaus by Caravaggio from the beginning of the 17th century, now at the National Gallery in London. The table is decidedly richer compared to that of Pontormo. Among the foods introduced by Merisi, foreign to the sources, there is also a fruit basket: a citation – in the appearance and the artifice of the protrusion from the support surface – of his previous Canestra di frutta, made at the end of the Cinquecento (Pinacoteca Ambrosiana, Milan). The Canestra represents the only still life known in the artist’s production, a forerunner of a genre that will establish itself from then on: the still life.

Mythological and historical recreations

Greek and Latin mythology, as well as some historical events, were particularly popular among Renaissance artists. This is true, for example, for Banchetto degli dei, related to the wedding of Peleo and Teti or Amore e Psiche.

This is the subject depicted in 1528 by Giulio Romano at Palazzo Te (Mantua), in the Chamber of Amore e Psiche. The scene is divided across the southern and western walls of the room. One fresco depicts the celebration of the gods, among whom Vulcano, Apollo, Dioniso, Amore, and Psiche can be identified lounging on a couch, and Cerere. The other fresco portrays the rustic banquet organized by the satyrs in honor of the newlyweds: an earthly counterpoint to the elevated, divine love of the first wall. Dishes, fruit baskets, and festoons animate both scenes, conveying the idea of lively abundance, even in the absence of actual dishes.

Appreciated since Mannerism onwards, the Banchetto di Cleopatra combines a taste for theatricality typical of the 17th and 18th centuries with several seductive aspects, including the magnificence of the court, the legendary beauty of the queen, and, obviously, the charm of her extreme gesture. This is well illustrated in the large canvas created in the early 18th century by Francesco Trevisani for Francesco Spada and still preserved at Palazzo Spada in Rome. The gastronomic rarities proposed by Marcantonio are presented in silverware and on a fruit tray visible in the background. However, the real protagonist of the work is the act performed by the queen, who with a graceful demeanor and resolute air, dissolves her pearl earring in a glass of vinegar before drinking it and thus ending the contest.

If up to this point food has predominantly an allegorical, decorative, or secondary character compared to the main subject, from the second half of the 16th century, we witness the development of two genres – successful and enduring over time – in which dishes play the leading role: genre painting and still life.

Genre painting and still life

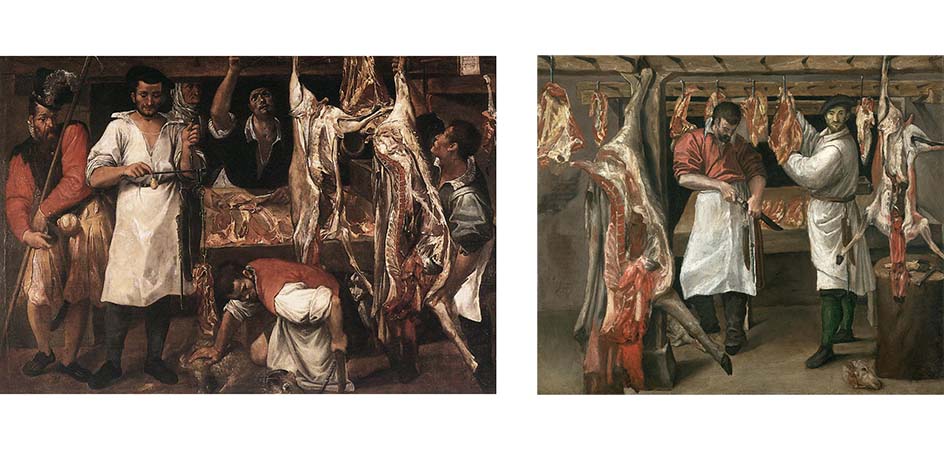

In the Netherlands of the late 16th century and in other Protestant countries, images with sacred subjects were banned from churches. This was a radical change, and artists suddenly found themselves orphaned by their main patron. However, the rise of a wealthy mercantile bourgeoisie eager to own art and precious objects became an opportunity for new buyers and new subjects. Genre painting reflects this change: customs, fashions, and habits of the time are represented in accordance with the sensibilities of the new patronage. Thus, in the Flanders and in Italy, scenes of domestic life, markets, workshops, and kitchens proliferate, even with grotesque or lascivious tones. Food, often excessive, indeed reminds us of the ephemeral nature of earthly pleasures. An example is the series by the Cremonese Vincenzo Campi created for the dining room of the Kirchheim castle, commissioned by the banker Hans Fugger around 1580, which includes La fruttivendola, showcasing an unprecedented vegetable opulence. In stark contrast, the group of canvases dedicated to the butcher shop by Annibale Carracci (Grande Macelleria at Christ Church Gallery, Oxford and Piccola Macelleria, at Kimbell Art Museum, in Texas) dating from the same years: coarse figures and hanging carcasses evoke disgust in the viewer, in open contrast with the Mannerist trend of searching for beauty.

The end of the 16th century also coincides with the birth of what will later be defined in the 19th century as still life. Flowers, fruit, musical instruments, inanimate objects: still life includes a wide variety of subjects, among which food is not always exclusively involved. Tables laden with dishes, desserts, game, fruits, and cheeses are some of the recurring themes in 17th century paintings from the Netherlands.

In Spain, however, a composition in confined and modest spaces is preferred (hence the name of the genre: bodegon, or cellar, tavern), as seen for example in the Natura morta by Velázquez at the Uffizi in Florence; while in Italy – in Rome, Florence, and Naples – this genre undergoes the great influence of Caravaggio and the scientific illustration of the Bolognese school.

Of Merisi, we have already mentioned the Canestra di frutta, but it is necessary to recall the Ragazzo con la canestra di frutta (1593-1594, Galleria Borghese, Rome) and the slightly later Bacco, at the Uffizi, in which the meticulous representation of fruit accompanies the illusionistic virtuosity of the cup of wine.

Finally, a female personality: Giovanna Garzoni, who with a delicate and fine touch creates harmonious and small-sized compositions. Her works include the Piatto con ciliegie, con due fichi e due nespole sul ripiano (1640-1650) and Il Vecchio Artimino (1649), both at Palazzo Pitti in Florence. The latter was commissioned by Don Lorenzo de’ Medici and represents a sui generis still life precisely for the presence of the old Artimino. In the foreground, artichokes, citrons, eggs, melons, apples, grapes, cherries, salami, and ham, pecorino cheese, broad beans, and a flask of wine, as well as the artichoke, a Tuscan vegetable and Medici pride, because it was imported by Caterina de’ Medici – who was fond of it – to the French court.

Are you interested in articles like this?

Sign up for the newsletter to receive updates and insights from BeCulture!

Last but not least, Giuseppe Arcimboldo. Active at the Habsburg court in the second half of the 16th century, Arcimboldo became famous for his bizarre images composed of food and naturalia in general. Anthropomorphic figures, similar to portraits, took the name of capricci and served to celebrate the universality of the patron.

Just mention works like Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe by Edouard Manet (1863, Musée d’Orsay, Paris) or I mangiatori di patate by Vincent van Gogh (1885, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam) or even the Campbell Soup by Andy Warhol to realize how influential the above-described genres have been for subsequent artists.

Even today, food occupies a large part of our interests and our entertainment. If there is one thing this brief excursion demonstrates, it is that food has always been on everyone’s mouth – and brush.