Understanding and appreciating an artwork goes beyond knowing its author, subject, and the era it comes from. There’s a fourth element that’s just as crucial: the technique. It’s not merely about categorizing a piece as a painting or a sculpture; one must delve into the specifics – what materials were used, the surfaces worked upon, and the tools employed. The chosen method of execution not only shapes the final piece but also serves as a testament to the artist’s prowess.

This holds particularly true for oil painting, a practice that, from its inception during the Renaissance, has significantly altered the course of art history.

Giorgio Vasari, in the opening of chapter 21 of his Vite, wholeheartedly praises this technique that emerged more than fifty years prior: “The discovery of oil-based color was a splendid invention and a great boon for the art of painting,” he pens. “This approach to coloring makes the hues more vibrant, and all it requires is dedication and passion. Oil yields a gentler, more nuanced, and delicate hue, allowing for easier blending and soft transitions. When applied fresh, the colors seamlessly merge, endowing the craftsmen’s figures with exquisite grace, vivacity, and robustness. Their work becomes so lifelike that the figures seem to emerge from the canvas, particularly when underscored by excellent design, creativity, and style.”

Now, let’s explore the origins and evolution of oil painting and examine its impactful legacy.

What is oil painting and how it differs from tempera

To fully appreciate the significance of oil painting, it’s crucial to grasp its essence and how it stands apart from techniques that appear similar, such as tempera painting. The art of painting is a triad: the pigment, the binder that secures it to the surface, and the surface itself.

Oil painting is characterized by blending pigments with fatty substances like walnut, linseed, or poppy seed oil to create a thick and sticky consistency. These oils undergo a purification process to remove mucilage, which leads to yellowing, and are deacidified to maintain the vibrancy of whites, greens, and blues.

For sheer tints and to moderate the drying pace, painters add plant-based essential oils, like turpentine essence from distilled conifer resins, or lavender, spike, or rosemary oils. Paintings can be crafted on various mediums, including wood, metal, or fabric. We’ll soon explore the intertwined histories of oil painting and canvas, the latter becoming the canvas of choice in the 14th and 15th centuries.

Tempera painting

As for tempera, the term (from “temperare”) traditionally means to mix colors to the right consistency using water and a binding agent like egg, milk, fig latex, glue, gum, or wax – anything but oil.

This definition, however, isn’t exhaustive since historical tempera paintings occasionally contained oily substances. Vasari even referred to mixtures of oil and varnish as tempera.

Tempera is essentially of two kinds:

- Lean tempera, a mixture of water and plant or animal glues, is vulnerable to moisture and tends to fade as it dries;

- Fat tempera, which is richer due to the use of oils, resins, and gums, results in a more enduring color.

The use of oil as a binder is an ancient practice, documented in Theophilus’s treatise from around 1100 and in Cennino Cennini’s mid-fourteenth-century Libro dell’Arte. Renaissance Italian masters were known for their hybrid techniques, applying thin layers of oil-resin paint over tempera. The chosen base for painting – whether it be wood, metal, stone, cardboard, canvas, or paper – required a preparatory layer known as an imprimitura to properly hold the color. Wood was the medium of choice for a long duration; medieval artworks were frequently tempera on wooden panels. A prime illustration of this method is Primavera by Botticelli.

The emergence of oil painting: from Flemish roots to Italian Renaissance

Beginning in the 15th century, oil painting began its march from Northern Europe’s chilly climes to the sun-drenched lands of Italy, quickly eclipsing the once-favored tempera method.

A pioneer of this art form was Flemish painter Jan Van Eyck (1390-1441), often mistakenly hailed as its creator. True, Van Eyck excelled in blending oils and resins, his approach marked by precision and consistency.

His work Man in a red turban, dated 1433 and residing in London’s National Gallery, stands as a testament to Van Eyck’s exceptional skill and his flair for rendering textures that almost defy reality.

Oil painting’s allure lay in its versatility and the creative liberties it offered – painters could vary the texture from thick to thin and employ a range of tools, from brushes to palette knives, or even their fingertips, a method favored by Tiziano. The addition of various essential oils could also tailor the drying time, allowing for a leisurely exploration of shades within a hue or a brisk application of contrasting colors.

Artists personalized their techniques to suit their visions. Antonello da Messina (1430-1479), hailed as the Italian progenitor of oil painting, laid down a hard gesso foundation on his panels, followed by a layer of cooked oil, onto which he layered colors, adding more oil to blend hues subtly. He’d let this base dry before finalizing with turpentine essence.

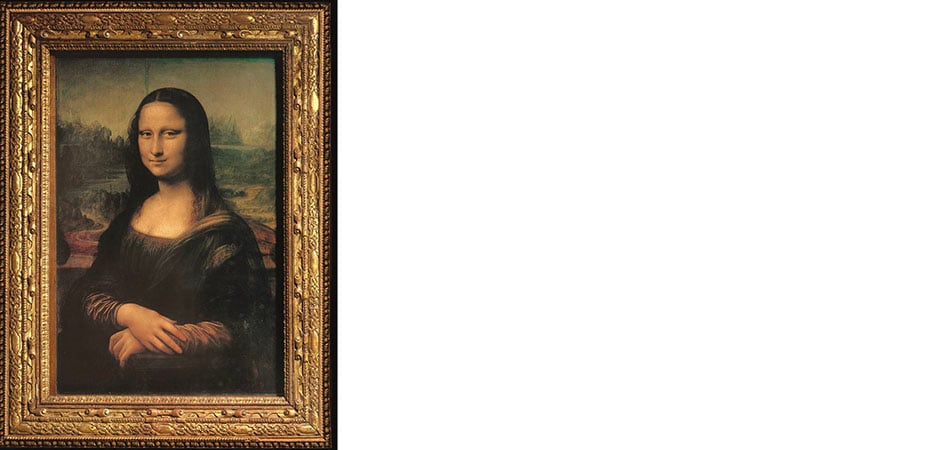

Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), in contrast, employed a distinct base for each section of his works Sant’Anna, la Vergine e il Bambino and the Gioconda – both jewels of the Louvre. He chose blue for the upper regions, red for the lower, and amber for the flesh tones, depending on the intended lightness or darkness of the final color. Leonardo’s use of thin, cooked walnut oil glazes bestowed a unique luminosity to his paintings, leaving no visible brushstrokes.

These mentioned masterpieces are but a glimpse into the world of oil on panel. However, as previously noted, the rising popularity of oil painting also owes a debt to the advent of canvas. This new medium, from the late 16th century onward, would come to dominate the art world, elevating oil painting to a nearly unrivaled status.

Canvas: the ideal foundation for oil painting

In the late 15th century, Venetian artists pioneered the use of canvas stretched across frames, a method that accommodated adjustments for the natural give and tension of linen or hemp canvases on custom-built, movable frames. The initial preparation of the canvas involved a delicate imprimitura: a fine layer of starch and sugar glue allowed to set for a day, followed by a couple of layers of gesso and glue, meticulously evened out with a spatula. This created a smooth white surface that could be toned with a wash of red or brown, or any color that would underpin the palette an artist, like Leonardo, intended to use. Masters such as Tiziano (1485/1490 – 1576) and Velazquez (1599 – 1660) tailored their canvas preparations to suit specific areas and color schemes within their works.

The canvas’s flexibility compared to the wooden panel made for a more liberated and dynamic brushwork, particularly with oil paints, enabling artists to vary their strokes from delicate dabs to expansive sweeps, building up color mass or finessing fine details. This synergy between medium and material was indeed a stroke of luck.

The concept of painting on fabric wasn’t entirely new, as evidenced by references to ‘panni’ and ‘cortine’ in extensive Medici collection records from the 15th century, though none of these pieces survive today. The real breakthrough was using canvas for oil paintings of substantial size.

Venice’s damp, salty air was the nemesis of fresco art, which led to the innovation of teleri, large frameworks of sewn-together canvases, mounted on moisture-treated walls. This design kept the artwork slightly off the wall, reducing environmental damage and allowing for the adornment of grand rooms without resorting to frescoing.

The practical benefits of canvas became quickly apparent. Unlike the laborious process required to prepare wooden panels, canvas preparation was straightforward and swift, which also translated into cost savings. Its lightweight nature made it transportable, facilitating simpler, more practical shipping solutions and aiding artists’ mobility, allowing them to carry their studio with ease. Consequently, the use of canvas opened a world of opportunities for remote commissions. During the Baroque period, artworks were often created off-site and later refined on the spot before being affixed to walls and ceilings.

Jacopo Bellini (1396-1470) was among the trailblazers to adopt canvas for extensive art series, with many contemporaries following his example. Mantegna (1431-1506), influenced by Venetian artistry, mastered the technique and played a role in its dissemination.

Caravaggio (1571-1610) consistently chose canvas over fresco for his grand designs, as it allowed him the dramatic chiaroscuro effects he could not achieve with fresco.

Are you interested in articles like this?

Sign up for the newsletter to receive updates and insights from BeCulture!

The palette: a practical and theoretical tool

With the rise of oil painting, another work tool, already known but not yet standardized, became necessary: the palette.

The binding action of the oil allowed pigments to be turned into a dense, rather malleable paste, and the palette facilitated the mixing of these colors to achieve desired hues and gradations. With the introduction of the palette, it was now possible to create variations, tones, and levels of brightness and transparency more deftly.

From the 16th century on, the practice of organizing and mixing colors before applying them to the canvas became both a practical necessity and a mental guide, capable of anticipating and revealing the painter’s intentions.

According to Vasari, the painter Lorenzo Di Credi (1456/1460 – 1536) operated with extreme diligence, preparing between twenty-five and thirty shades on the palette, from the lightest to the darkest, using a different brush for each. It seems, however, that Rembrandt (1606-1669) used separate palettes for each area of the painting according to an order he maintained throughout his life.

In the early 17th century, painters and theorists engaged in lengthy discussions on the use and organization of the palette, and even in the time of Cézanne (1839-1906), it was a subject of reflection and debate.

The history and theory of color in painting owe much to this iconic tool.

Social implications of oil painting

We have seen the practical and artistic consequences of using oil paint on canvas and its unstoppable spread. Like all great inventions, this technique also had social ramifications, contributing to a change in the artist’s very image.

The quicker canvas preparation process, the increased availability of colors, and the reduced cost of raw materials freed painters from various craft steps, instead emphasizing the creative moment and personal style.

Focus shifted increasingly from the workmanship to the features of the painting, which gained fame not from the use of precious materials – such as gold and lapis lazuli – but from the prestige of the author himself, now even more capable of achieving effects and results never seen before.

Without this technique and its tools (primarily the canvas and palette), it is likely that the history of art and its protagonists as we know them today would not have existed.