Just a fifteen-minute walk from Castel Sant’Angelo, Palazzo Spada, acquired by Cardinal Bernardino Spada in the early 17th century, has been a historical icon thanks to the cardinal and his lineage who resided there until the dawn of the 20th century. The namesake Galleria Spada, established as a state museum in 1927, is home to an extensive collection of baroque paintings and artifacts, initiated by the cardinal and expanded by subsequent generations.

Now serving as the headquarters of the Consiglio di Stato, Palazzo Spada stands out as one of the city’s most beautiful structures, where the grandeur of the Renaissance and Roman Baroque coalesce. A journey through the museum’s halls offers a vivid reimagining of life in a genuine 17th-century noble residence, with a wealth of art and genius at every turn. This is why a visit to Rome would be incomplete without experiencing the architectural marvel that is Palazzo Spada and its impressive collection.

The Spada collection

The core of the Galleria Spada‘s collection, as initiated by Bernardino Spada from Bologna, was later enhanced by a series of discerning acquisitions, including those by his great-grandson, Fabrizio Spada, between 1643 and 1717. The matrimonial union of Orazio Spada to Maria Veralli in 1636, as well as the contributions from Maria Pulcheria Rocci, wife of Prince Clemente, added both ancient and contemporary pieces to the already distinguished collection.

The baroque gallery, returned to its original grandeur by art historian and critic Federico Zeri, unfolds across four rooms, each reflecting the passage of time. These spaces showcase the impressive array of paintings, arrayed in layered rows, complemented by original furniture, sculptures, and architectural flourishes like coffered ceilings and friezes.

A curated walk through some of the most significant pieces of this esteemed collection will help the reader appreciate its renowned value.

Portraits of Bernardino Spada by Guido Reni and Guercino

In the first room, known over time as the Stanzone dei Papi, Anticamera nuova, or stanza del soffitto Azzurro, stand out two portraits commissioned by Cardinal Bernardino to Guido Reni (1575 – 1642) and Guercino (1591 – 1666).

The first is an oil on canvas in which we can admire the refined balance between intimacy and solemnity. The cardinal is portrayed seated at his desk, writing a letter to the pope, the phrase “Beatus Padre” just discernible on the page before him. A luxurious drape frames the right of the scene, while to the left, the grand archive of his correspondence subtly conveys the daily life of the cardinal, without losing the iconic grandeur of the moment, underscored by the careful composition and his deliberate pose.

Guercino’s work, in contrast, presents a stark half-length portrait with no backdrop. Here, Bernardino’s gaze meets ours directly, with a seriousness and focus that suggests the weight of his thoughts. Held in his hand and presented outward is the blueprint of Forte Urbano of Castelfranco dell’Emilia, a project he was charged with overseeing by papal decree. The portrait reveals Bernardino’s authority and the engagement he commands from viewers through a powerful visual dialogue.

The 16th century portraits by Passerotti and Tiziano

In the Sala II, the museum houses its most ancient canvases. This room was once encased in wooden panels crafted by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, which have since been lost but gave the space its name, the Stanza alla fiamminga.

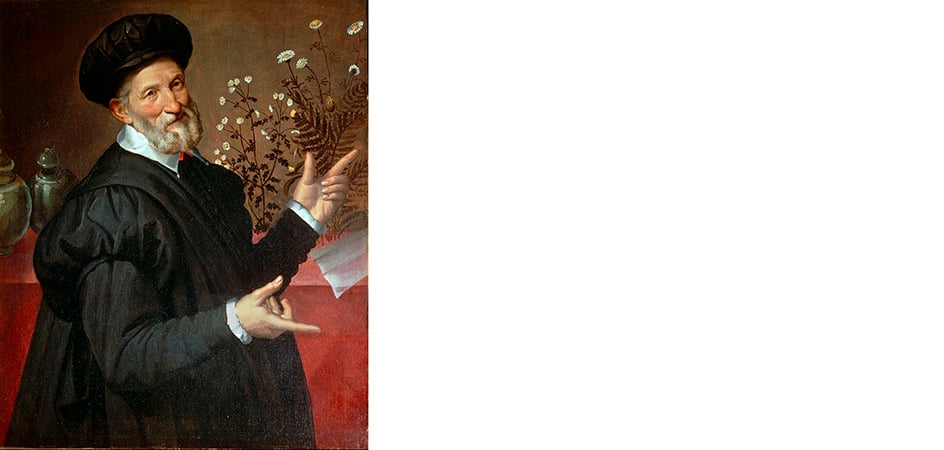

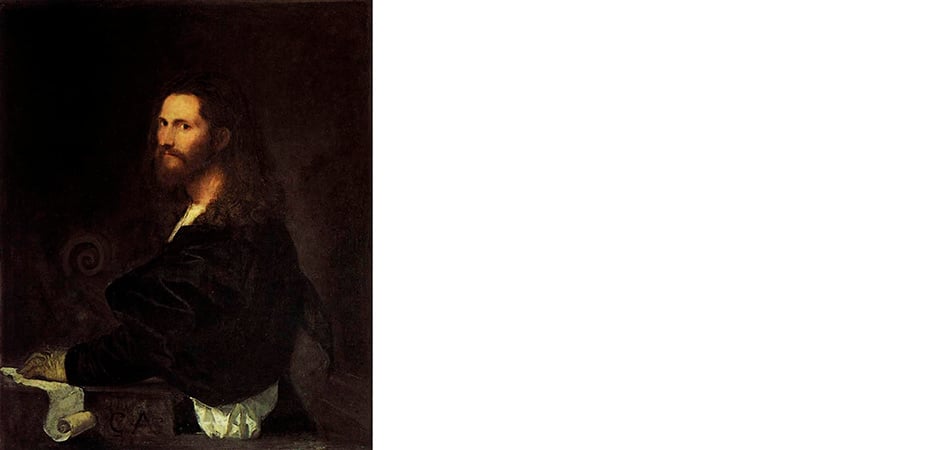

Standout pieces include the Ritratto di botanico by Bartolomeo Passerotti (1528 – 1593) and the Ritratto di violinista by Tiziano Vecellio (1488/90 – 1576).

Even if the botanist’s identity remains a mystery, the portrait is a hallmark of innovation from that era. The subject’s expressive face, dynamic hands, and the peculiar setting with chamomile plants in the background all herald the portrait’s uniqueness, hinting at the painter’s – and the buyer’s – interest in the natural sciences.

Tiziano’s youthful work is equally captivating, capturing a violinist mid-turn, his gaze about to lock with the viewer’s as he clasps a scroll. Renowned for his oil painting technique, Tiziano conveys the dynamism and realism of the movement with a muted palette of grays, blacks, and browns, creating a striking visual tension between the violinist’s penetrating look and the tangible texture of his attire against a subtle backdrop evoking a spacious Renaissance hall.

Painting of the Queens

Sala IV of Palazzo Spada, through its history of transformations, now welcomes its visitors with the lively decorative motifs by Roman painter Michelangelo Ricciolini, adorning the ceiling, walls, and window recesses.

Prominent in this room is La morte di Didone by Guercino, a grand depiction of Queen Didone’s suicide in the wake of Enea’s departure. The scene plays out under the watchful eyes of her sister Anna and others surrounding her, as Enea’s ships recede in the background. The painting’s dramatic composition amplifies its moral message: the tragic end of those who sacrifice reason for passion. Originally commissioned for Queen Maria de’ Medici of France by Bernardino, the cardinal himself acquired it for 400 scudi when political upheavals forced Medici to flee to Belgium.

A second regal subject comes to life in Banchetto di Marcantonio e Cleopatra by Francesco Trevisani (1656 – 1746), ordered by Fabrizio Spada. It portrays the storied contest of opulence between the Roman general and the Egyptian queen. As told by Plinio, the two challenged each other to create the most lavish feast. While Antonio toiled for exotic delicacies, Cleopatra showcased her supremacy through a singular act: she dissolved a priceless pearl from her earring into a cup of vinegar and drank it, a scene captured with late Baroque theatrical flair by Trevisani.

The paintings by Caravaggio: Orazio and Artemisia Gentileschi

The collection presents a stunning array of paintings by Caravaggio in one venue, showcasing works by artists influenced by Caravaggio from Italy and beyond.

Among them are the Gentileschi, Orazio and his daughter Artemisia, connected to Caravaggio by both friendship and artistic kinship.

The David con la testa di Golia by Orazio Gentileschi (1563 – 1639), initially misattributed to Caravaggio, was only rightly acknowledged in the late 19th century.

The subject’s portrayal, the nuanced depiction of flesh and fur, and the deft use of lighting align with Merisi’s style, designating this work as a 17th century masterpiece.

This painting, along with two by Artemisia Gentileschi (1593 – 1652) in the collection, came as part of Maria Veralli’s dowry to Orazio Spada.

We spotlight the Madonna con Bambino by Artemisia, an oil on canvas that, in Caravaggio’s vein, brings a biblical scene to relatable life.

The Virgin, dozing while nursing, symbolizes a maternity that is divine yet palpably earthly, blending the sacred subjects’ spirituality with the tender humanity of their actions.

These masterpieces reside within the original spaces of the palace which, in spite of their opulent decor, maintain a sense of intimate scale.

The Colonnata or Prospettiva by Borromini

This same intimate ambiance can also be discovered within the Giardino Segreto, accessible at the conclusion of the first floor’s tour. The courtyard is the keeper of one of the Baroque era’s most famous and striking deceptions: Francesco Borromini’s Colonnata.

Constructed in 1653 for Bernardino Spada, it is aptly named the Prospettiva for it intentionally evokes the age-old architectural technique.

Thanks to meticulous mathematical calculations, Borromini’s Colonnata beguiles onlookers with an artful illusion. It initially presents itself as a 30-meter-long passage, yet upon traversing it, one realizes it spans merely 9 meters. The gallery’s clever construction plays on optical effects to give an impression of immense depth. Its columns are designed not to run in parallel but to converge at a singular vanishing point, shrinking in size from the top downwards and towards the back, as the floor simultaneously rises.

This remarkable creation serves a greater purpose than mere spectacle: while strolling in his garden, the cardinal could illustrate to his guests the transient nature of worldly appearances, much like the Colonnata itself, which is not all that it seems. It stands as both a moral caution and a stunning testament to architectural genius.

Are you interested in articles like this?

Sign up for the newsletter to receive updates and insights from BeCulture!

Originally, the corridor concluded with a mural depicting a dense forest, but in the 19th century, Prince Clemente Spada replaced it with the statue of the warrior still present today. This statue, too, plays a role in the illusionistic scheme: despite appearing majestic from afar, it reveals its surprisingly modest size up close.

The facade of Palazzo Spada

The 16th century facade of Palazzo Spada stands as a testament to the Roman Renaissance, immaculately preserved and artfully divided into four distinct tiers.

The rusticated stonework of the ground floor sets the stage for the second level, adorned with niches housing statues of Rome’s Illustrious Men: Romolo, Cesare, and Traiano. The next tier is distinguished by intricate stucco decorations.

Also prominent is the Spada coat of arms, a later addition which disrupts a sequence of medallions showcasing Cardinal Girolamo’s emblem: a dog resting at the base of a blazing column, beneath the motto “utroque temporum” (at all times), symbolizing unwavering devotion to faith.

The uppermost tier presents tablets that encapsulate the achievements of these renowned figures.

The facade’s rich tapestry of symbolic and decorative elements, complete with garlands, mythical figures, and classic motifs of Renaissance Roman art such as candelabra, makes this one of the representative facades of stucco artistry and the era’s architectural grandeur — a fitting introduction to the Palazzo’s interior treasures.

Curious to explore further? If you have yet to experience Palazzo Spada and its splendid collection spanning the 17thand 18th centuries, secure your ticket now to visit the Galleria!