Few things can evoke contrasting feelings like still life, especially older ones: some are passionate about it, while others consider it a minor genre. To better understand its importance and charm, let’s retrace its history and evolution, focusing particularly on the 17th century, to which some of the most famous still lifes belong.

The origins of still life: from antiquity to the Middle Ages

How is still life defined? To simplify, we can say that this genre includes everything that is not history painting. In other words, these are works without a narrative, depicting neither human deeds nor events (be they religious, mythological, or otherwise), but instead represent the inanimate world of objects. Fruits, flowers, food, tableware, books, musical instruments, work tools: everything can be the object – and thus the subject – of still life.

According to this definition, we can trace the beginnings of this art back to Roman times, particularly in wall and mosaic paintings made between the 1st century BC and the 1st century AD in ancient Roman villas and the buildings of Pompei and Ercolano.

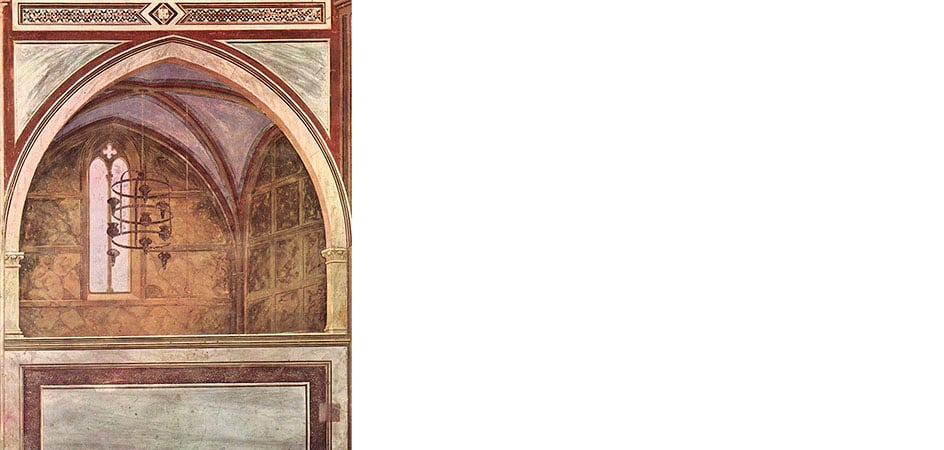

However, its official antecedent is commonly recognized in the two frescoed Coretti by Giotto in the Cappella degli Scrovegni (1303-1304), which pave the way for the painting of objects. Here, the Tuscan Master represents two settings seen from below, with a bifora (twin window) and a cross vault from which an elaborate wrought-iron lantern hangs, without any human subjects or explicit narrative motives.

The 15th and 16th centuries: objects gain autonomy

In the 15th century, Flemish painting already stands out for its marked preference for realistic settings. Biblical episodes and saints’ lives are often set in domestic places, characterized by furnishings and everyday objects – laden with symbolic meanings – meticulously described by the artists of the time. An example of truly sublime naturalistic detail is achieved in the famous Trittico Portinari by Hugo van der Goes, 1477-1478, housed in the Galleria degli Uffizi. The work, commissioned by the Florentine merchant Tommaso di Folco Portinari, consists of a central panel enclosed by two side shutters decorated on both sides. The interior, revealed only during certain liturgical moments like Lent, depicts the Nativity: the Child and the Virgin at the center, surrounded by angels and shepherds in adoration, while San Giuseppe observes the scene in prayer. In the foreground, a double vase of flowers containing lilies, irises, columbines, and carnations, all varieties that recall the Virgin’s virtues.

But the true push towards the genre’s autonomy comes from the second half of the 16th century, when, following the Protestant Reformation, the depiction of sacred scenes is banned in the Netherlands and other northern countries. This event forces artists to seek new themes and commissions: the then-flourishing merchant bourgeoisie adds to the traditional ecclesiastical patrons. This success leads to the so-called genre painting spreading beyond borders. Thus, markets, shops, and kitchens with workers and goods alternate in late 16th century paintings: the golden age of still life is just around the corner.

The 17th century: the golden age of still life

In the 17th century, still life establishes itself as an independent genre, spreading on a European scale. The Netherlands and Germany are considered its birthplace: as we have seen, the social fabric and interest in representing the material qualities of things favor a new and substantial production of still lifes.

But these works multiply elsewhere in Europe too. In Italy, for example, the most flourishing centers are Rome, the Lombardy area, and Naples, with some prominent names also in Florence.

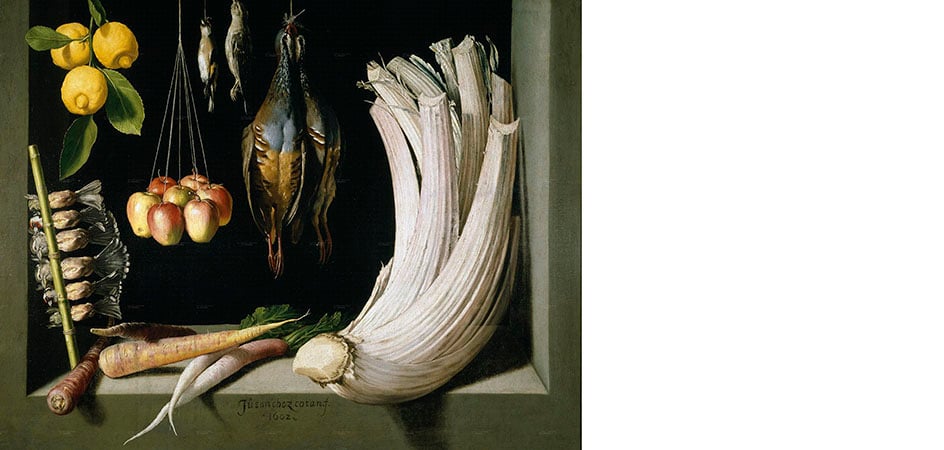

Spanish artists adhere to this new genre by favoring the painting of food (the so-called bodegónes, from the Spanish for tavern, cellar); while in France, still life spreads later than in other countries, with artists drawing inspiration mainly from Flemish production.

Meaning and subgenres of still life

Why did still life become so popular? Besides the aforementioned social and cultural events – and the growing interest of artists in representing reality in all its manifestations – the reasons lie in the underlying meaning of these paintings. Still life allows for the symbolic expression of the precariousness of existence and the transience of worldly things, a theme dear to 17th century culture.

The allegory is read, more or less evidently, in all subgenres of still life:

- Floral compositions: among the most requested themes by the market, the bouquet – an expression of the beauty of creation – owes its success also to the “fever” of flowers that characterizes especially the Netherlands (dating to this era is the so-called tulip mania, which led to the disastrous commercial speculation on tulip bulbs).

- Fruit compositions: like flowers, fruit is also much appreciated by artists and patrons. Colors, textures, shapes: fruit is a stimulating subject not devoid of allegorical meanings.

- Poultry and game: halfway between genre painting, animal painting, and trompe-l’oeil, these works often have gloomy connotations and a moralizing subtext that alludes to the fleetingness and vanity of man.

- Laid tables: food in art finds one of its highest expressions in banquets. They range from more austere and modest compositions to sumptuous tables where the opulence and variety of animal species and exotic objects testify to the richness of bourgeois and aristocratic kitchens of the time.

- Moralizing compositions: the vanitas of earthly existence is emphasized in compositions depicting skulls and other bones (symbols of death), hourglasses, candles, clocks, music scores, and ancient books (time), mirrors, jewels, and coins (worldly life).

3 famous still lifes among european trends

To understand the variety and styles of different authors, let’s examine three paintings known for their pictorial quality.

The first cannot but be the Canestra di frutta (circa 1597-1600, Milan, Pinacoteca Ambrosiana), the only known still life by Michelangelo Merisi, known as Caravaggio.

Caravaggio’s interest in reality – including inanimate objects – is evident from his early works: the Ragazzo con canestra di frutta (circa 1593-1594, Rome, Galleria Borghese) and the marvelous Bacco (circa 1598, Uffizi) are proof of this. However, the Canestra represents an unrivaled pinnacle in Merisi’s production and the Ambrosiana collection, so much so that even its founder, Cardinal Federico Borromeo, had to resign himself to the fact that “for its incomparable beauty and excellence, [the painting] remained alone.”

The mimetic precision of the brushwork is combined with the artifice of the basket’s position, which seems to protrude from the plane, while the uniform background enhances the plasticity of the fruit. Many interpretations exist of the work, also called Fiscella (a wicker basket) by the cardinal, but the juxtaposition of fresh and rotten fruits and withered leaves with healthy ones undoubtedly refers to the passage of time and the fragility of worldly life.

A few years later, another cardinal demonstrates a clear preference for still life. Giovan Carlo de’ Medici, brother of Grand Duke Ferdinando II, goes so far as to purchase thirteen works by the Flemish Willem van Aelst, known as the Olandese, who specialized in the genre. During his Florentine stay, Van Aelst produces numerous works, including the Vaso di fiori con orologio (1652) and its contemporary pendant, Natura morta con frutta e vaso di cristallo. The canvases, now housed in the Galleria Palatina in Florence, were found in the cardinal’s private room at his city residence (the Casino degli Orti Oricellari in Via della Scala), along with Raffaello’s Madonna del Cardellino (Uffizi) and the Ritratto del Cardinal Bibbiena (Palazzo Pitti), and the Madonna della cesta by Correggio (National Gallery, London).

The Vaso di fiori con orologio, in particular, strikes for the chromatic balance of the flowers, which stand out against the dark background (a typical trait of the artist), and the meticulous rendering of the marble surface of the shelf and the blue silk cloth. Contrasting the apparent liveliness of the bouquet, an open watch reveals its mechanisms, emblematic of the inexorable passage of time.

The last but not least name we want to mention here is Juan Sánchez Cotán, one of the earliest exponents of the genre in Spain. His canvases stand out for their small size and recurring scheme: fruits and vegetables against dark backgrounds and bare shelves are depicted with a severity that is as poetic as it is strict. A repetitiveness appreciated by patrons, more interested in the subject than in the uniqueness of the work. An exception is his Natura morta con volatili appesi, ortaggi e frutta (Madrid, Prado Museum) made in 1602. The composition, normally minimal and limited to a few foods, is enriched here with numerous dead and hanging birds, an explicit reminder of earthly finitude. The black background further emphasizes the chosen elements, meticulously painted and illuminated by a lateral light: a decisive chiaroscuro that dramatizes the scene even more and evokes solutions made by Caravaggio.

Sánchez Cotán creates the work while still in Toledo, at the peak of his career, just a year before deciding to join the certosini order and leave everything behind. But his style would become a model, and many artists would follow in his footsteps.

Beyond the 17th century: still life as an artistic device

Beyond its most flourishing period, in the 18th century, still life essentially reprises the achievements of the previous century, tempering the symbolic intent in favor of a purely decorative one. Although there are excellent examples, in summary, we can say that the 18th century does not shine for originality or inventiveness.

On the other hand, the 19th and 20th centuries are quite different. With the rise of artistic movements, still life enters the repertoire of painters through the lens of specific formal and iconographic programs, collective or personal. For the Impressionists, flowers, fruits, and inanimate objects are chosen subjects as volumes struck by light, leaving us with admirable paintings by Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Camille Pissarro.

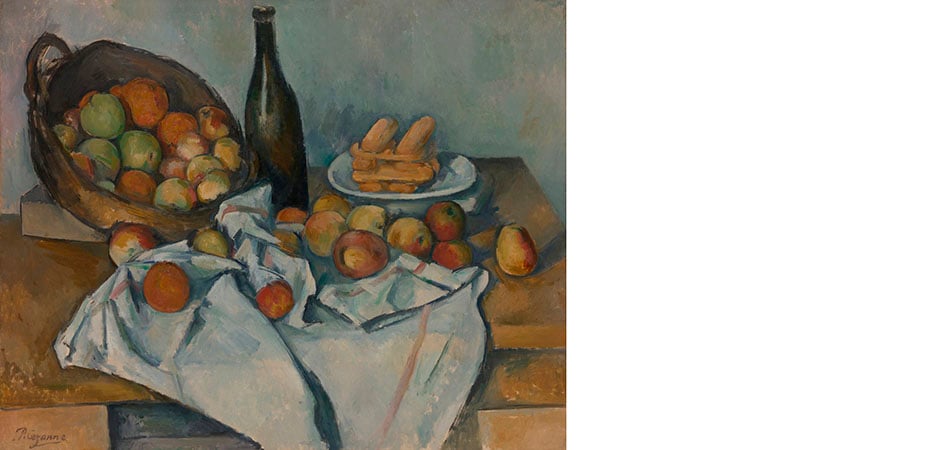

A different and more individual search qualifies the painting of Paul Cézanne, where all kinds of mimesis are abandoned: objects are simplified into their essential forms, spaces compressed, and perspective planes multiplied from different viewpoints. The Cesto di mele (circa 1893, Chicago, Art Institute) is one of his most famous still life paintings.

Cézanne’s influence was fundamental for the genre’s evolution, as seen in Henri Matisse, leader of the Fauvist movement in the early 20th century, and Pablo Picasso, father of Cubism: both authors of still lifes that concentrate their poetics.

A unique and misunderstood voice was that of Vincent van Gogh: his painting technique of fast and vigorous strokes reflects his feelings and turmoils (also the focus of Julian Schnabel’s successful film), but it enjoyed no success during the artist’s lifetime.

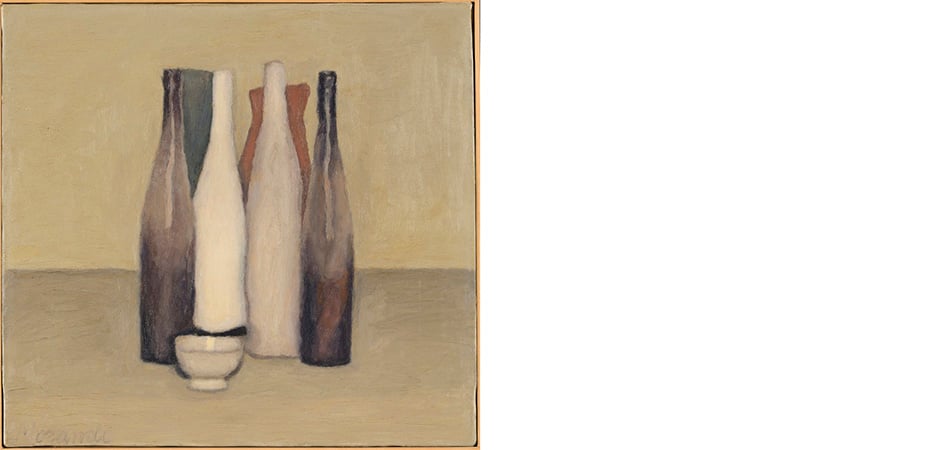

Coming to the late 20th century, we cannot overlook Giorgio de Chirico, the creator of Metaphysical Art, and, of course, Giorgio Morandi, whose series of bottles certify the painter’s progressive projection towards achieving an extreme and very personal compositional balance.

Are you interested in articles like this?

Sign up for the newsletter to receive updates and insights from BeCulture!

But, if we look closely, Dada, Pop Art, and almost all subsequent movements have perhaps confronted the motif of still life, adapting and stretching it to its limits.

Quite an achievement for a genre initially perceived as minor and that in Italy received a name only in the 19th century, long after its spread and the creation of works that we can rightly call masterpieces today.