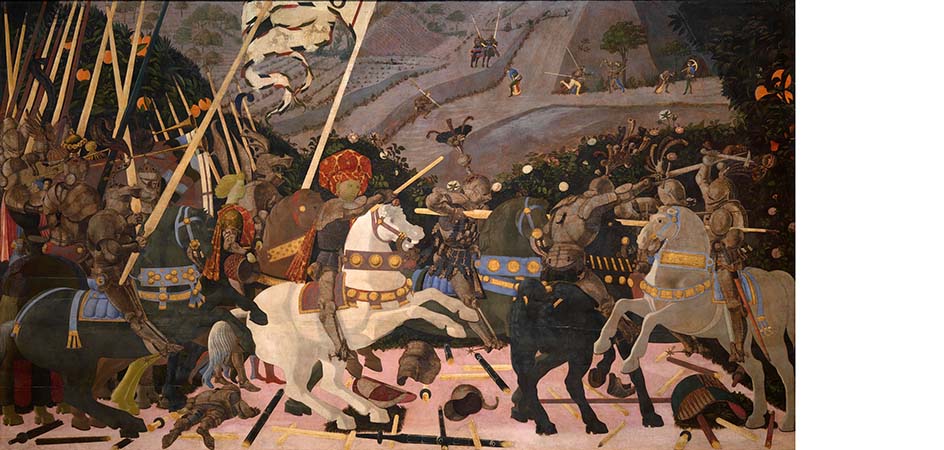

It happens almost every day. Someone, while visiting the Uffizi, finds themselves spellbound before the Battaglia di San Romano by Paolo Uccello – not only because it’s the first non-religious subject in the Galleria’s display, but also for its strikingly unusual appearance. Its colors, composition, and style stand apart from everything around it. Indeed, it’s one of the most accomplished works by that curious and singular personality that was Paolo Uccello. Driven by “whims” and “oddities” (as Vasari1 says), he managed to unite mathematical precision with a sense of fantasy, narrating a real historical event through images.

A triptych divided among three museums

Before we delve into the composition itself, it’s important to remember that La Battaglia di San Romano at the Uffizi is part of a series of paintings originally conceived as one unified work, but now split among three museums. The theme is the same, though each panel captures different moments: the battle’s onset in the panel at London’s National Gallery, the clash and the enemy’s unseating in the Florentine panel, and the decisive intervention of allied troops in the panel at the Louvre in Paris.

A Medici inventory from 1492 lists the triptych as part of the bedroom furnishings of Lorenzo il Magnifico in today’s Palazzo Medici-Riccardi on Via Cavour (then Via Larga) in Florence. For a long time, this led to the belief that Cosimo il Vecchio, Lorenzo’s grandfather, commissioned the work to celebrate a contemporary military victory.

A recent discovery, however, has revised this plausible but incorrect hypothesis. A payment document from 1438 shows that Lionardo Bartolini Salimbeni, a wealthy Florentine merchant who distinguished himself in battle, acquired the works. He likely hired Paolo Uccello for the very reasons once attributed to Cosimo.

Lorenzo il Magnifico, captivated by the panels’ beauty, must have later obtained them from Salimbeni’s heirs and moved them to his residence.

This new understanding helps date the paintings (produced between 1435 and 1440) and explains the later additions – also by Uccello – to their upper sections. Initially curved, perhaps intended as lunettes, they were completed with extra painted segments. For the Uffizi panel, for example, orange trees were added on the left, a clear nod to the Medici (known at the time as mala medica, or “medicinal fruit”). This symbol, widespread in Medici patronage, also appears in Nascita di Venere by Botticelli.

But when did the depicted event take place and why was it so important?

The subject: the clash between Florence and Siena

Rarely mentioned in standard history books, the Battaglia di San Romano played an important role in the political landscape of its time. We’re in the era of the Signorie, and the feuds between guelfi (allied with the Pope) and ghibellini (backed by the Emperor). Florence, then a Republic, was defending its territories from the expansionist aims of the Visconti of Milan, who had long sought to conquer Tuscany to gain direct access to the sea.

In 1432 at San Romano, the Florentine army, led by the capable Niccolò da Tolentino, clashed with the army from Siena (age-old rivals of Florence) and their allies from Lucca and Lucchese and Lombardy armies.

It is this commander we see in the foreground of both the London panel – charging into battle on his white horse – and the Uffizi panel, dislodging another knight, Bernardino della Carda. Particularly despised by the Florentines for having first pledged support and then betrayed them, Bernardino’s defeat at the center of Uccello’s triptych represented not only a historic fact but also a source of pride at the expense of a treacherous enemy.

In the final panel, now in Paris, we recognize Micheletto Attendolo da Cotignola. His intervention proved decisive in securing Florence’s victory when the Republic risked being overcome.

Iconography and style of the Battaglia di San Romano at the Uffizi

Set against a pastoral landscape, infantrymen and armored cavalrymen fight ferociously. Long, white, and red lances frame the scene, directing the viewer’s gaze toward the painting’s main vanishing point. In the center, a knight with a covered face (Bernardino della Carda) is struck in the chest, seemingly about to fall, as his horse rears up as if to fling him off. All around, a chaos of fallen horses, knights, faces, bodies, and weapons vividly conveys the turmoil of battle.

Led by four knights with lancia in resta2, the group on the left (the Florentines, recognizable by their banner on the trumpet) appears to have the upper hand. On the right, the Sienese struggle: the angle of the lances and crossbows suggests their disadvantage. In the background, amidst plowed fields, a hunting scene unfolds with a splendid greyhound chasing hares – some interpret this as a metaphor for the battle itself. The artist’s signature (Pauli Ugeli Opus) can be read on a scroll emblazoned on a shield discarded at the lower left.

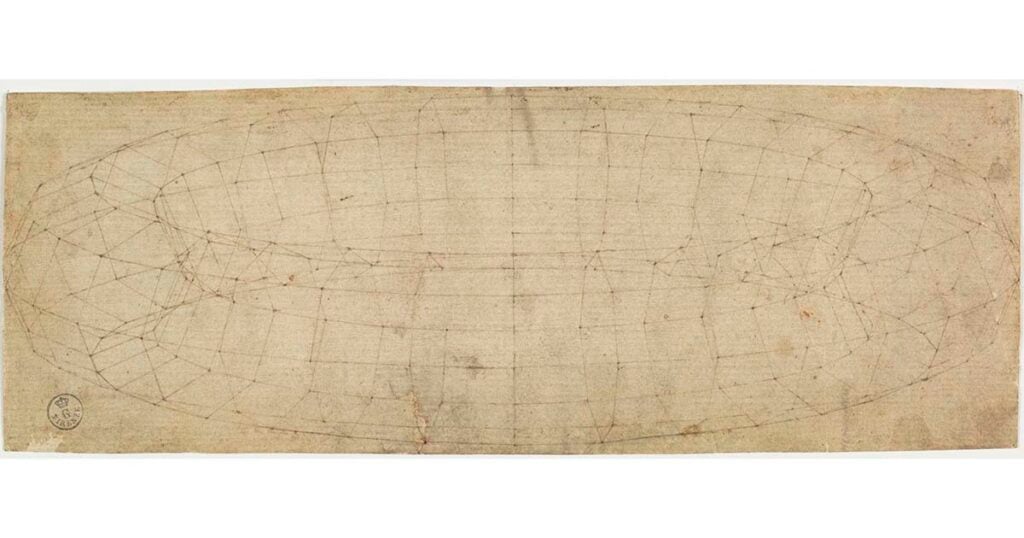

Even today, traces of gold and silver leaf remain, hinting at how the horse harnesses and other armor details were once richly adorned. Yet what astonishes modern viewers most is the painting’s strikingly modern feel, so unlike its contemporaries, and the artist’s explicit fascination with perspective and geometric forms. Paolo Uccello employs a mathematical approach to explore multiple viewpoints and their effects, pushing representational and distortive experiments to extremes. This is evident in the dramatically foreshortened horse lying at the bottom, the prone knight on the right – mirroring and contrasting a figure in the London panel – and in the depiction of mazzocchi. These fashionable Florentine headdresses appear in both rigid forms (hexagonal or octagonal in section) and twisted versions. Uccello was deeply intrigued by them, as shown by a drawing preserved today at the Uffizi.

The coloring of the three panels also strays from convention, imbuing the Tuscan painter’s work with a nearly fairy-tale quality. Unlike other Renaissance artists, Uccello did not probe the psychological depth of his figures; instead, he focused on what Vasari called “matters of perspective”.

Are you interested in articles like this?

Sign up for the newsletter to receive updates and insights from BeCulture!

Paolo Uccello and the passion for perspective

Words of both admiration and reproach come from Vasari in his Vite. “Paolo Uccello,” he writes, “[…] gifted by nature with a subtle and sophistic mind, cared for nothing but investigating certain difficult and nearly impossible aspects of perspective, which, while fanciful and beautiful, hindered him so greatly in his figures that, as he grew older, he painted them ever worse”.

This obsession, which Vasari saw as detrimental, may have led to the artist’s impoverished later life. It certainly drew criticism from his friend Donatello, who urged him to abandon his experiments, and also from his family.

According to Vasari, when Uccello worked late into the night on his prospective studies, and his wife and daughter Antonia (a nun and one of the few known female Renaissance painters) called him to bed, he would reply: “Oh, how sweet is this perspective!”

Perspective was not Uccello’s only passion. He also loved animals, though unable to afford live ones, he contented himself by painting them, covering his home’s walls with small animal-themed works.

Born to a barber-surgeon (as was common then) from Pratovecchio, Paolo di Dono apprenticed in Lorenzo Ghiberti’s workshop during the creation of the first doors of the Florence Baptistery. He showed an early fondness for birds – perhaps the reason he became known as “Uccello” (“bird” in Italian).

The Battaglia di San Romano splendidly illustrates his love of perspective and animal representation, blending them into a masterpiece that transcends not only its own time but all those that followed. It has even led some to see anticipations of Cubism and Surrealism, long before they existed.

It’s surprising to learn that the triptych remained intact at the Uffizi until the mid-19th century, when it was split up. Judged to be inferior copies at the time, the two side panels were sold to the National Gallery and the Louvre – a decision that was deeply regretted later.

While it’s impossible to see all three panels reunited in person today, simply standing before the Uffizi’s painting is a moving experience. It brings you closer to one of the most distinctive and sophisticated minds of the early Florentine Renaissance. Book your visit now!

1 Giorgio Vasari (1511–1574), an artist, architect, and writer at the Medici court, authored Le vite de’ più eccellenti architetti, pittori, et scultori italiani, da Cimabue insino a’ tempi nostri (published in 1550 and again in 1568 with additions), a fundamental text in the historiography of Italian art.

2 The expression “lancia in resta” comes from the lance support (resta) mounted on the right side of the armor’s breastplate, used to brace the lance during combat. Introduced around the mid-15th century, it could be fixed or movable. To set a lance “in resta” means to ready it for battle.