Isabella d’Este, Elizabeth I of England, Isabella I of Castile… Retracing the history of the 16th century, we encounter many powerful and strong-willed women known for their decisive roles in the political and strategic events of Europe at the time.

This is not the case for the women artists of the Renaissance: figures who, with rare exceptions, remained excluded from the main stage, victims of the conventions of the time or unfortunate personal circumstances.

Fortunately, thanks to their character and great talent, some female artists defied prejudices and difficulties to emerge in a predominantly male society.

Becoming and artist between the 16th and 17th centuries

For women of the 16th century, an artistic career was either closed off or filled with obstacles. There were practical impediments: they were prohibited from accessing the Academy – and thus from live nude models – and they couldn’t attend workshops, domains of men who could threaten their honor and good name. There were also preconceptions, like those expressed by Vasari in his Vite¹ when, speaking of women, he writes: “Nor have they been ashamed, to snatch from us the boast of superiority, to put their tender and very white hands into mechanical things and among the roughness of marbles and the harshness of iron”. As if to say that their purity and delicacy were ill-suited to dirty and arduous trades like painting and sculpture.

A paradox, especially considering that, according to the myth reported by Plinio in his Naturalis Historia, drawing – the basis of all figurative arts – was invented by a woman, Kora or Callirhoe of Corinth.

So, how did one become an artist in those times? There were mainly three paths.

Taking refuge in a vocation, real or presumed, and unleashing one’s talent protected by convent walls.

Having the good fortune of being the daughter of enlightened artists who would instruct and support them.

Being a girl from a good family who received education in letters, music, and painting, and turning the latter into a profession. Such was the case, for example, of one of the most popular and prolific artists of the 16th century: Sofonisba Anguissola.

Sofonisba Anguissola (1532-1625)

The eldest of six sisters – all painters – and one brother (the only one who did not pursue the career), Sofonisba was the daughter of Amilcare Anguissola of Cremona, a cultured and forward-thinking man who had her study under the painter Bernardino Campi.

Sofonisba soon demonstrated great skill in portraiture and particularly in self-portraiture – a genre she embraced partly due to societal limitations (she was not allowed to portray nude subjects from life) and in which she showed a marked ability to convey the psychological dimension of her subjects.

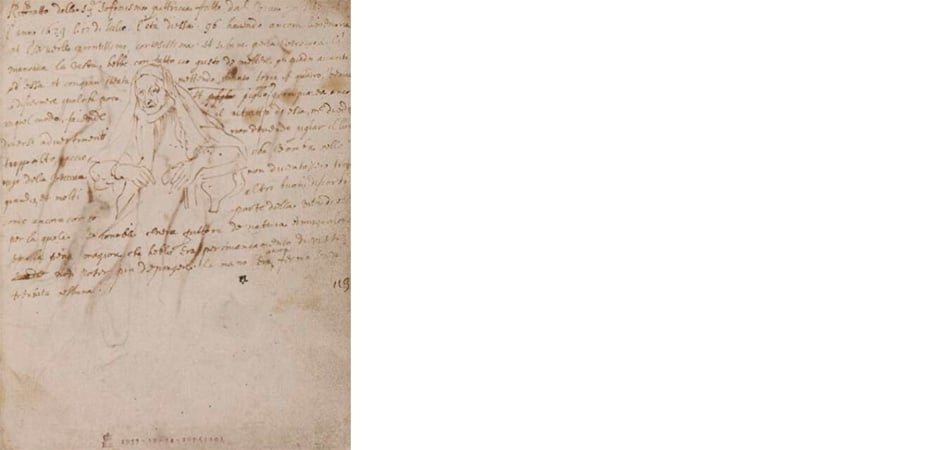

This is evident in Fanciullo morso da un granchio (c. 1555, Naples, Museo di Capodimonte), a drawing praised by Vasari and said to have passed through the hands of Michelangelo, whom Sofonisba met in Rome. The authenticity of the boy’s grimace, captured at the exact moment he feels pain, defines this work as a link between Michelangelo and Caravaggio (who, some years later, created his Ragazzo morso da un ramarro, now in the National Gallery, London).

Naturalism characterizes all of Anguissola’s works, including more enigmatic and complex pieces – like the famous Bernardino Campi ritrae Sofonisba Anguissola (1559, Siena, Santa Maria della Scala) – or the self-portrait from 1552-1553 housed in the Uffizi, where the painter appears engaged at her writing desk. This pose was common among female artists of the time, showcasing their competencies in study and music as well.

Esteemed and appreciated for her extraordinary artistic talents, Sofonisba also led a rather long and eventful life. Becoming a lady-in-waiting and court painter for Emperor Filippo II of Spain and Isabella of Valois, she married by proxy Don Fabrizio Moncada of Palermo. The marriage was short-lived; Don Fabrizio died in an ambush in 1578. Deciding to return to Cremona, she disembarked in Livorno and Pisa, and – swiftly and against her family’s wishes – married Orazio Lomellini, a captain of a galley of the Repubblica di Genova, whom she likely met during her journey.

This union was more enduring, and the couple lived in the Ligurian city for thirty-five years before moving – in 1615 – to Palermo, where Lomellini owned many properties. It was here that Sofonisba died at the age of ninety-three, nearly blind but aware of being recognized as one of the most important painters of her time. Proof of the high esteem she enjoyed is the drawing by Van Dyck made during his visit to Sicily in 1624 (London, British Museum). The Flemish artist portrays her seated in an armchair, elderly but still lively, as he notes on the same sheet: “[…] still possessing a sharp memory and mind, most courteous, […] her greatest sorrow was due to her loss of sight, no longer being able to paint: her hand was still steady without any tremor”.

Lavinia Fontana (1552-1614)

At that time, Bologna stood out for a peculiarity: it was the city that hosted or gave birth to the most female artists. Certainly aided by the presence of the university – accessible even to women – which fostered a climate of study and general openness. In this context, Lavinia Fontana was born, daughter of painter Prospero Fontana, who eagerly encouraged her artistic inclination. Equally important for Lavinia’s career was her husband, Gian Paolo Zappi, a mediocre painter who decided to set aside his own career to support his wife (and mother of his eleven children!), acting as a sort of early manager. A successful strategy, considering that today 135 documented works bear Fontana’s name, although far fewer remain.

Like her colleagues, Lavinia specialized in portraiture with brilliant results, as confirmed by the miniature self-portrait from 1557 (where she too, like Anguissola before her, depicts herself at the writing desk) now housed in the Uffizi. Despite the beauty of this portrait, we want to focus on another painting, known for its undisputed quality and the record it holds.

Lavinia Fontana is indeed the first to paint mythological subjects, and this is the first nude painted by a woman. The piece is Minerva in atto di abbigliarsi (1613, Rome, Galleria Borghese), created in Rome for Cardinal Scipione. The goddess, undressed and viewed from behind, turns her gaze toward the viewer while approaching the sumptuous dress placed on a stand. At her feet lies armor, and just behind, a seated Cupid handles the helmet. The setting opens onto a view of Rome—recognizable by the dome of St. Peter’s—with the spear, olive tree, and owl, attributes of the deity, visible. The goddess’s beautiful features stand out against the dark background, which emphasizes the intimate and secluded nature of the scene.

It is likely that Cardinal Borghese had seen a similar painting made a few years earlier by the same artist and requested a comparable canvas for himself. It was common practice to produce multiple copies of the same theme, also as a form of self-promotion. For a woman, gaining notoriety and securing new commissions was indeed challenging. One strategy was to gift powerful individuals with their paintings, as well as create different versions to send to potential buyers. This explains the numerous variants of Ritratto di dama con cagnolino by Fontana.

Are you interested in articles like this?

Sign up for the newsletter to receive updates and insights from BeCulture!

Marietta Robusti (1554-1590)

Marietta Robusti, eldest daughter of the renowned Tintoretto (Jacopo Robusti) born from a premarital relationship with a courtesan, had a decidedly less permissive father. Deeply attached to his daughter and determined to keep her close, Tintoretto taught her painting, just as he did with his children from his marriage to Faustina Episcopi, even disguising her as a man to introduce her to workshop activities. Marietta quickly displayed her talent, to the extent that she was sought after by both the Spanish court of Filippo II and the Austrian court of Emperor Massimilano. Tintoretto, however, would not allow her to leave.

Nothing could separate them – not even marriage, which Tintoretto carefully arranged with a local gentleman to ensure Marietta remained in Venice, where she prematurely died in childbirth.

Of “La Tintoretta,” as she was nicknamed, little remains today. It is possible that her portrait from around 1580, now in the Uffizi, is her own work and thus a self-portrait. Here, the young woman is depicted in three-quarter view, gazing toward the audience, wearing a finely pleated white silk dress and a single piece of jewelry – a pearl necklace.

In her left hand, she holds a musical score, while her right rests on a harpsichord. Once again, a non-pictorial setting that reveals the musical talent for which she was also known.

Her fame, coupled with the symbiotic relationship with her renowned father, has fueled historians’ curiosity, who are still engaged in examining her authentic works.

In addition to the artists mentioned, we want to remember the sculptress Properzia de’ Rossi (1490-1530), who participated in the construction of San Petronio in Bologna, and Plautilla Nelli (1524-1588), the first Florentine painter whose works we know.

These women preceded the celebrated Artemisia Gentileschi, whose skill, strength, and impetuous character are impossible to ignore and who inaugurated the Baroque era.

But that is, as they say, another story and another era, which will soon be the subject of our in-depth exploration.

In the meantime, seeking out works by female artists in public and private collections pays homage to the memory of these women and the fundamental role they played in the history of art.

1 An artist, architect, and man of letters at the Medici court, Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574) was also the author of Le vite de’ più eccellenti architetti, pittori, et scultori italiani, da Cimabue insino a’ tempi nostri (published in 1550 and expanded in 1568), a foundational work for Italian art historiography.