Clergymen, knights, kings, and princes, but also children, noblewomen, saints, and courtesans: many subjects are portrayed wearing or handling jewelry and precious objects. But what are the functions of these painted ornaments? And what are the intentions behind them?

Tracing the history of jewelry in art means simultaneously retracing that of goldsmithing, fashion, culture, and commerce. It’s a fascinating journey that can hardly be contained within the space of a single article.

Jewelry gradually acquires new meanings, shaped by the social context and the personalities of both the artist and the subject. Materials and styles also change over time, influenced by fashion trends, historical events, and the creativity of those who represent them.

That’s why, in tackling such a vast topic, we’ve decided to focus here only on certain types of jewelry – those more frequent and easier to recognize, or particularly curious and emblematic – and on an era that shines for its production and inventiveness: the Renaissance. Guiding us on this journey are numerous works, famous also for the depicted ornaments. Let’s begin!

The historical and artistic context

Known for its clarity, attention to detail, and rich symbolism, Flemish painting of the 15th century reflects the growing interest of patrons in goldsmithing, which was experiencing significant technical and stylistic development during these years. Beyond Duke Filippo il Buono and his court, the new mercantile bourgeoisie, eager to demonstrate their achieved status, also became significant patrons for artists. As a result, portraits of men and women multiplied, depicted with precision in their clothing and jewelry – precious artifacts representative of their social condition.

The reproduction of reality also characterizes Italian art, which, from the mid-century, fell under the spell of Flemish art and imitated its language. Added to this is the metaphorical interpretation of gems, which, according to ancient tradition, were emblems of virtues and thus significant of the character of those who wore them.

It was common for painters, sculptors, and architects to train in goldsmiths’ workshops before practicing the major arts; from this comes their skill in representing stones and jewelry.

Are you interested in articles like this?

Sign up for the newsletter to receive updates and insights from BeCulture!

Ring: seals of faith, rank, and marital bond

Rings have been widespread since ancient Egypt, used as amulets and symbols of the wearer’s identity. In Rome, rings adorned the phalanges of all fingers except the middle one, which was already associated with a vulgar gesture and was called digitus infamis. The preferred finger was the ring finger, so named precisely because it was the seat of the jewel – a custom that continued through the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, reinforced by the belief that a vein connected that finger directly to the heart. Indeed, in paintings, rings worn on the ring finger often signify emotional bonds. However, it’s worth noting that, besides the ring finger of both hands (especially the left), in Italy, the wedding ring was also worn on the index fingers.

This aspect makes it challenging to identify which is the wedding ring in the Ritratto di Maddalena Doni displayed at the Uffizi alongside her spouse and counterpart, the Ritratto di Agnolo Doni, both by Raffaello (1504–1507).

Maddalena wears three gemmed rings, two on her left hand: a ruby on the ring finger and a table-cut diamond on the index finger. Both the ruby, symbolizing love, and the diamond, emblematic of enduring commitment, are plausible candidates for a wedding ring – or wedding rings, since it was not uncommon for the groom to give more than one. They find an almost perfect correspondence with Agnolo’s rings – a detail certainly not accidental, highlighting the couple’s union and the reciprocity of their feelings.

The ruby worn halfway down the right-hand finger, in line with the fashion of the time, could indicate the love not yet realized for a hypothetical future child.

Staying on the marital theme, rings also offer useful clues for interpreting other paintings. For example, the man depicted by Lorenzo Lotto in his Ritratto maschile (circa 1542, Rome, Galleria Doria Pamphilj), though still unidentified, has been interpreted as a widower. Indications include his melancholic expression and the pointed index finger (a common gesture in Renaissance art) toward the two rings on his little finger – again, a diamond and a ruby, probably both belonging to his wife. The custom of the time dictated that upon a wife’s death, the jewelry given by the husband would return to his possession so he could use it for subsequent marriages.

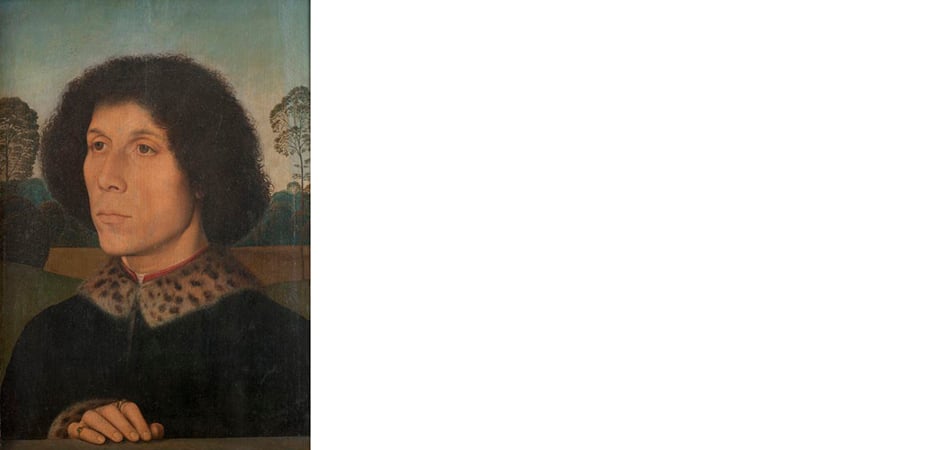

A different purpose distinguishes chivalric and heraldic rings, which indicated belonging to a certain elite, as well as those equally demonstrative in some Flemish portraits. One notable example is the Ritratto d’uomo con paesaggio by Hans Memling (circa 1475, Florence, Uffizi). The man’s right hand is adorned with rings on the index and little fingers. The ornament on the index finger recalls the function of a seal, suggesting an important role and its use in signing various documents. The gem à cabochon, though uncertain, is likely an emerald or a turquoise – common in men’s jewelry for their supposed ability to ward off dangers. Their presence on the right hand (commonly associated with manual work) serves to reaffirm the man’s high status, engaged in some intellectual or leadership activity.

Pendant: ornament and talisman

The pendant – already known in Roman times – was highly appreciated during the Renaissance as an ornament with strong symbolic and protective value. Initially simple in form, featuring a set colored stone and a drop-shaped hanging pearl, the pendant evolved to become more elaborate, featuring human figures, animals, and mythical creatures.

The aforementioned Ritratto di Maddalena Doni once again offers an exquisite example of this multifaceted decorative, metaphorical, and protective value. In her pendant, we can recognize a ruby, symbolizing love and charity – believed to provide comfort and vitality; a sapphire, signifying faith and acting as a shield against diseases and pitfalls; and a small emerald, indicative of beauty. The emerald, set in the belly of a unicorn (an emblem of chastity), alludes to gestation – and thus to virtuous fertility – hoped for by the couple, who were still without children at the time. Completing the jewel is a baroque pearl, carrying the same meaning.

Quite different is the pendant worn by Eleonora Gonzaga della Rovere in the Ritratto painted by Tiziano (1536–1538), also housed in the Uffizi. Upon close inspection, one notices a cross completing the diamond-studded Christogram IHS (Iesus Hominum Salvator), a symbol of faith – a type of artifact quite common in the 16th century as a talisman against evil and misfortune.

But the pendant isn’t the only striking detail depicted in the painting. It’s impossible not to focus on the marten with a golden head encrusted with precious stones that the duchess holds in her right hand. The stuffed animal was worn by the wealthy ladies of the time, carried in hand or hung from a chain tied around the waist, as in this case. The head and paws were replaced with gold and gem equivalents, making it a highly prized and costly accessory – so much so that it was banned by a sumptuary law in the mid-century.

Speaking of curious pendants, a special mention goes to the toothpick. Its use was known since antiquity, but only in the 16th century did it become fashionable to wear it as a pendant. Made of gold and embellished with gems and enamels, it often took the form of a horn – the ultimate amulet. Thus, besides cleaning teeth, it also guaranteed the wearer’s safety. A famous example is the Ritratto di Lucina Brembati by Lorenzo Lotto around 1518 (Bergamo, Accademia Carrara).

Pomander: a precious remedy against bad odors

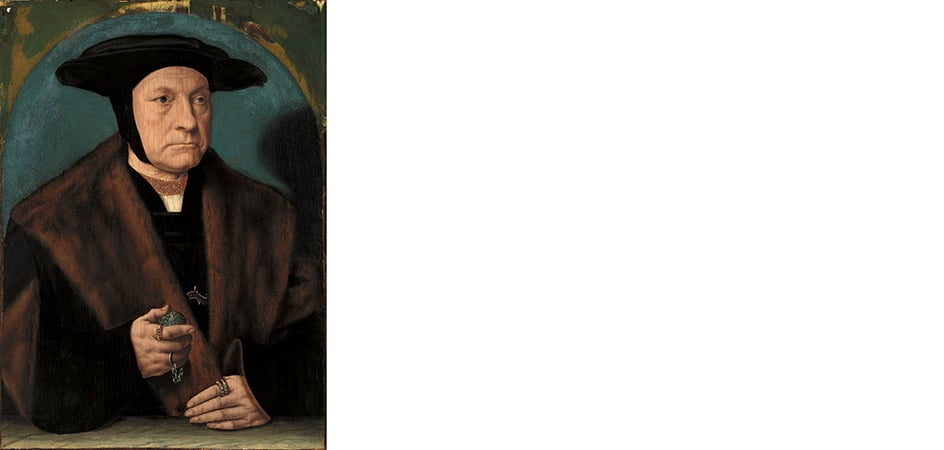

What do the Ritratto di Clarissa Strozzi by Tiziano (1542, Berlin, Gemäldegalerie) and the Ritratto di un uomo della famiglia Weinsberg by Bartholomäus Bruyn il Vecchio (circa 1538–1539, Madrid, Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection) have in common? Both feature a pomander. In the first, it’s hanging from the chain around the girl’s waist; in the second, it’s held in the man’s hand.

A pomander is a small sphere divided into openable segments containing essences and spices. In an era when hygienic habits left much to be desired, the pomander served to mask bad odors and emit pleasant fragrances. For the same reason, necklaces, earrings, and bracelets were perfumed with fragrant pastes and ambergris.

Moreover, it was widely believed that perfume could disinfect the air, eliminating the danger of contagion during plagues.

According to astrological medicine, these substances also retained the positive energies of their elements, which were transmitted to their owner through the pomander – a blend of pragmatism and magic we’ve already encountered in other jewelry from this period, making them even more intriguing to the modern eye.

Pearl earrings: between scandal and ambiguity

Disappeared in the West during the Middle Ages, earrings experienced a resurgence during the Renaissance, following the rediscovery of classical art with its numerous images of bejeweled Roman matrons.

Particularly loved – and ambiguous – were pearl earrings. We find them in numerous paintings by Tiziano, including the already mentioned Ritratto di Eleonora Gonzaga della Rovere and his enigmatic Venere di Urbino (circa 1538, Florence, Uffizi). This coincidence, along with the similarity in the women’s features, even led to speculation that they were the same person – a hypothesis later abandoned in light of documentary evidence confirming the duchess’s reluctance to pay for the “nude woman,” a painting strongly desired by her son Guidobaldo della Rovere, who referred to it as such.

Yet, both women wear similar jewelry – a detail that adds to the difficulty of interpreting the Venere.

We know that pearls were associated with the virginal purity of Maria and were often used as ornaments in paintings depicting her. On the other hand, they just as frequently appear as attributes of Venere, the goddess of beauty and carnal love.

It’s also worth noting that in Venice, pearl earrings were forbidden to both unbetrothed young women and courtesans. So how do we explain their presence – along with other jewelry typical of marital union, such as rings and bracelets – on the ears of Tiziano’s nude and sensual Afrodite del Vecellio? Perhaps as a reference to a virtue that is only seemingly contradictory, composed of beauty and virginity: courtesan and new bride coexist, each a reflection of the other.

Once again, art serves as a privileged gateway to discover literally precious stories that might otherwise remain little known. Our exploration of the jewelry adorning men and women of the Renaissance has allowed us to delve into the lives, loves, and passions of the time.