How much can a kiss convey? And how many forms of love can it express? When you think about it, such a simple and human gesture hides a great variety of meanings, so it’s natural to find it in art, represented in countless ways and styles.

To showcase the versatility of this subject, we’ve chosen ten kisses that illustrate just as many types of love: from the passionate to the allegorical.

Mythological affections: the sensuality of Eros’s kisses

The revival of classical art and literature during the Renaissance led to the rediscovery of mythological tales, including those featuring Eros as the protagonist.The god of Love – Cupido to the Romans – has always been subject to numerous interpretations regarding his powers and origins (he was, among others, both the son of Afrodite and present at the goddess’s birth). Starting from the Hellenistic age, however, his appearance became codified, and Eros took on the form of a winged child armed with a bow and arrows. It’s in this form that we find him in many ancient works, often multiplied into various amorini (the Sarcofago con gli Eroti atleti from around 140-150 AD, now in the Uffizi, is an example), as well as in Renaissance works and beyond.

L’Allegoria dell’Amore by Bronzino

A subtle yet highly sensual kiss is depicted between the youthful Eros and Venere by Agnolo di Cosimo di Mariano, known as Bronzino. The Allegoria con Venere e Cupido (1540-1550, London, National Gallery) is one of his most enigmatic paintings. “He made a painting of singular beauty,” writes Vasari in his Vite1, “which was sent to King Francesco in France, containing a nude Venus being kissed by Cupido, with Piacere on one side and Giuoco with other loves, and on the other Fraude, Gelosia, and other passions of love”.

It’s probable that the artist was inspired by Venere e Cupido by Pontormo, his mentor (1530, Florence, Galleria dell’Accademia), where the goddess appears intent on stealing an arrow while Cupido tries to kiss her.

Bronzino’s panel is certainly more provocative and crowded: Eros brings his lips close to his mother’s while squeezing her breast and encircling her head to steal her crown. Afrodite, in turn, has both hands occupied: with her right, she grasps an arrow, and in her left, she holds Paride’s golden apple. Their pale bodies contort in extreme poses – typical of Mannerist iconography – standing out against a background populated by figures, masks, and animals with allegorical meanings. It’s a complex painting where all facets of love coexist, including: voluptuousness and purity (the two protagonists), Gelosia tearing her hair, Frode (the girl with inverted hands and claws), Follia or Piacere distributing roses, and Tempo looming from above.

Amore e Psiche by Canova

The theme of Amore e Psiche, already present in classical sculpture, had a significant influence on artistic imagination at least until the 18th century. Dating from this period is the eponymous sculptural group created by Antonio Canova, now housed in the Louvre in Paris. Commissioned by Colonel John Campbell in 1787 but never delivered due to his financial problems, it was purchased by Gioacchino Murat and sold to Napoleon in 1808.

Amore e Psiche depicts the climax of the mythological story, when Cupido – having descended into the Underworld to save Psiche from the cruel fate Venere had condemned her to – awakens her with a kiss. Canova represents the lovers in an embrace that is both ethereal and carnal, embodying an abstract and earthly beauty simultaneously. Just observe the harmonious intertwining of their arms, the contact of their bodies (with the light yet perceptible pressure of Eros’s hand on his beloved’s breast), the expressions on their faces, and the rendering of the marble material that seems alive.

And the kiss? It’s there, suspended: the two are immortalized a moment before their lips meet, already quite close but not yet united, in a gesture of great delicacy and erotic intensity. A masterpiece of Neoclassicism, the work is striking for the infinite viewpoints from which it can be admired.

Are you interested in articles like this?

Sign up for the newsletter to receive updates and insights from BeCulture!

The kiss that gives life: Pigmalione e Galatea

Just as Psiche receives a life-giving kiss from Eros, Galatea gains life from the kiss of her creator, Pigmalione. Once again, myth (as told by Ovidio in his Metamorfosi2) provides the theme for a pair of paintings that have become famous for their originality.

We’re referring to the two Pigmalione e Galatea by painter and sculptor Jean-Léon Gérôme, both from 1890 and both set in his own studio.

In the first, part of a private collection, the statue is portrayed from the front, her legs still marble and the rest of her body animated by vital energy as she bends to kiss the artist. In the second, housed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the scene repeats almost identically, but the woman-sculpture is seen from behind, and a small Cupido hovers in the air.

This second version perfectly captures the impetus of the action, its vitality and authenticity, making it almost possible to hear the smack of the kiss and feel Pigmalione’s touch on Galatea’s pale skin.

Solemn kisses: gospel narratives in Giotto’s frescoes

It’s not just about love: the kiss is also a symbol of betrayal, and one stands above all others.

The Sacred stories recount how Giuda used a kiss as a signal for the soldiers to arrest Gesù. This episode has been depicted by many artists (including Cimabue, Dürer, Caravaggio, and Van Dyck), often characterized by emphasis and agitation: guards and apostles clash in an animated tangle of weapons and dark despair as Giuda approaches the Master. The same occurs in Giotto‘s fresco in the Cappella degli Scrovegni (1303-1305, Padua), but here the kiss is isolated at the center of the scene, demonstrating the artist’s ability to convey not only the realism of the bodies but also the psychological depth of the characters.

Giuda leans toward the Savior, his face distorted in the grimace of a kiss that makes him appear even more animalistic and repulsive. The profound exchange of glances between the two reveals all the emotional weight of the moment: Cristo seems to peer into Giuda’s soul with stern resignation, and the tension of the kiss – incomplete yet inevitable – is palpable.

This is a stark contrast to the intimate, though equally solemn, dimension of another kiss present in the same cycle of Giotto’s frescoes: that between Anna and Gioacchino, locked in a tender embrace that alludes to procreation.

The perfect kiss: the pursuit by Rodin and Brancusi

Desire and the sensuality of bodies are central themes in numerous works by Auguste Rodin, who in 1880 was commissioned by the French state to create the Porta dell’inferno, intended for an art museum that was never completed. Inspired by Dante, Rodin had envisioned placing Paolo and Francesca kissing beneath the Pensatore. As narrated in the Divina Commedia, the two lovers were discovered by her husband (his brother) while reading the story of Lancillotto and Ginevra.

After reconsideration, the artist separated the group, turning it into a standalone sculpture exhibited in 1887. Il Bacio(1882, Paris, Musée Rodin) owes its title to the public who, lacking other indications, named it so.

The work, with its embrace full of passion, was met with acclaim, and copies were made in various materials. The artist was commissioned to create a second, enlarged version in marble, completed almost ten years later.

Yet Rodin was not satisfied. He reportedly said about it: “The embrace of the kiss is certainly graceful, but I found nothing in this group. It is a theme treated according to tradition, a subject complete in itself but artificially isolated from the world around it: a large ornament sculpted in a predictable way that focuses attention on the two characters instead of opening wide horizons to the dream”.

When, at the beginning of the 20th century, Constantin Brancusi arrived in Paris and spent about two months in Rodin’s studio, Il Bacio was at the height of its success.

This theme immediately fascinated him, leading him to pursue it for almost forty years, employing techniques and achieving results very different from his master’s. Unlike Rodin, who prepared clay models before working the marble, Brancusi started directly with the stone and, like a modern Michelangelo, brought out the form. A simplified form, reduced to its essence and therefore universal: in Brancusi’s Baci, the subjects are almost unrecognizable, sculpting the very essence of the kiss itself into a single block.

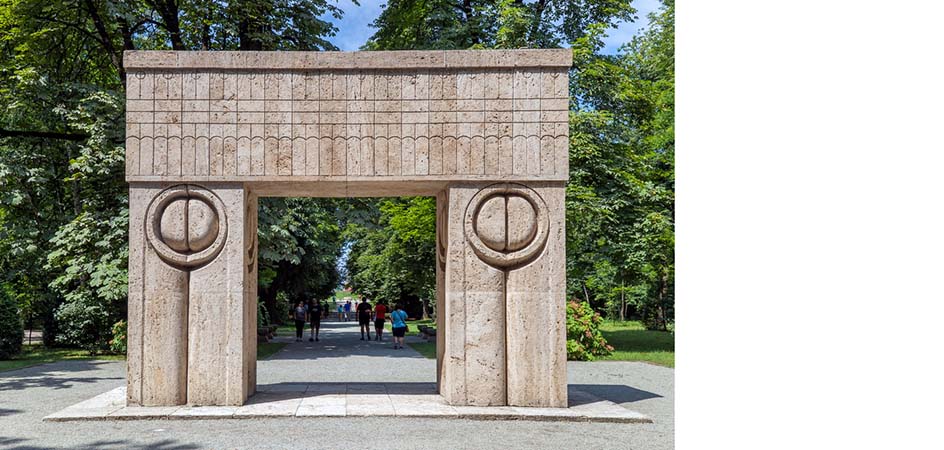

His first Bacio dates back to 1907 (Museum of Art of Craiova, Romania, the artist’s homeland) and already showcases the typical traits recurring in his subsequent numerous variations, including the Porta del Bacio (1935-1938, Târgu Jiu, Romania), where the stylization of the kisses inscribed in the pillars is at its peak.

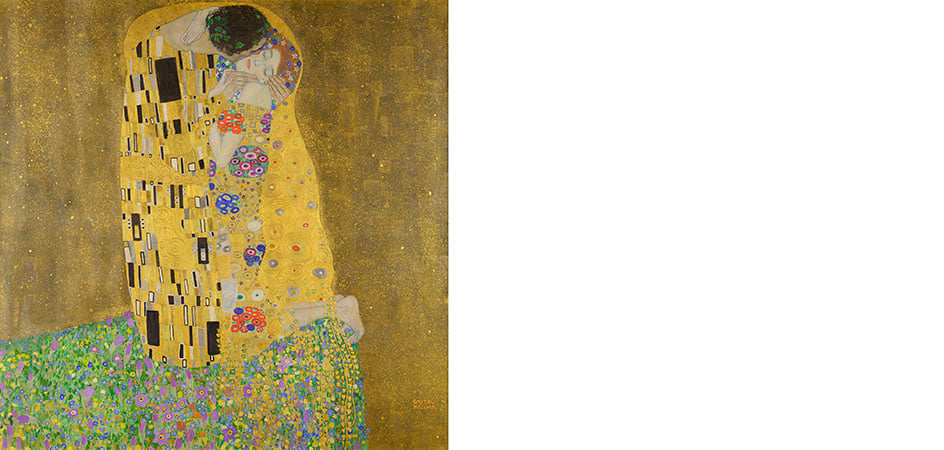

The kiss at the center of human experience: Klimt

During the same years that Brancusi began his series of kisses, another artist tackled the theme.

Il Bacio or Gli amanti (1907-1908, Vienna, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere) by Gustav Klimt is one of the most famous works in Austrian art. The canvas belongs to the artist’s so-called Golden Period, during which Klimt developed an innovative technique, blending gold leaf with oils and bronze paint. The painting depicts a couple wrapped in richly decorated garments as they embrace on a flowered meadow, at the edge of a precipice.The faces, hands, and other uncovered parts are the only recognizable details of the two lovers who surrender to the ecstasy of love against an abstract and timeless background. It’s a kiss both passionate and languid, through which Klimt offers an allegory of love as the focal point of human experience.

Astonishment and devotion: the kiss from Picasso to Chagall

Besides being a seducer in his private life, Picasso was also a prolific creator of kisses, but one stands out among the rest. It’s Il bacio from 1969, housed in the Musée Picasso in Paris. Here, Picasso abandons the almost cannibalistic voracity that characterized his earlier paintings (such as Il bacio from 1925, in the same museum, with bodies entangled and mouths fused into a single opening with strong sexual symbolism) to portray a scene of clearer affection.

The drawing is linear, allowing us to recognize the two profiles perfectly united in a kiss that is both sensual and mature. The man’s raised eyebrows and wide-open eyes seem to suggest a kind of joyful astonishment. At the time of its creation, Picasso was almost ninety, and we can imagine that – after a life of conquests and amorous fulfillment – he was somewhat amazed to still experience and depict such feelings.

In stark contrast is the approach of another artist who spanned almost the entire 20th century: Marc Chagall. A Russian painter who became a naturalized French citizen, Chagall dedicated numerous paintings to his first wife, Bella Rosenfeld, including Il compleanno (1915, New York, MoMA). Reality and dream intertwine here – as in all his work – to create a scene of great sweetness. Inside an apartment detailed meticulously, Chagall floats towards his wife to kiss her: his body light, his head bending backward in an unnatural and awkward pose. The ultimate meaning is that of a sincere, strong, and serene love, confirmed and celebrated on Bella’s birthday (hence the title).

With Chagall, we conclude our journey through kisses in art, but the list is long, and we may revisit it to tell you about artists like Edvard Munch, Francesco Hayez, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Jean-Honoré Fragonard, as well as Man Ray, Robert Doisneau… Because the kiss is charismatic and universal, capable of turning us all into unexpected voyeurs.

1. Artist, architect, and man of letters at the Medici court, Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574) was also the author of Le vite de’ più eccellenti architetti, pittori, et scultori italiani, da Cimabue insino a’ tempi nostri (published in 1550 and in 1568 with additions), a foundational work for Italian art historiography.

2. Le Metamorfosi is an epic poem written by Publio Ovidio Nasone between 2 and 8 AD. Centered on the theme of transformation, it contains some of the most famous stories in Greek mythology.