Italian gardens stand alongside architecture, painting, and sculpture as one of the Renaissance’s most enduring legacies. These gardens are celebrated for their harmonious balance and refined elegance, embodying a cultural heritage and detailed aesthetic pursuit that sought to express itself through the orchestrated arrangement of nature. In the 16th century, villas served as the perfect canvas to blend natural and man-made elements into a harmonious new order.

As with all things, time has shaped the Italian Garden, which has adapted and changed, obscuring some of its original design. Yet, by understanding its beginnings and distinctive characteristics, we can still trace and appreciate the essence of its early splendor.

A brief history of the Italian Garden: from antiquity to the 18th century

To grasp the roots and distinctive features of the Italian Garden, one needs to take a succinct journey through its history. It is a design scheme, a way of organizing and experiencing outdoor space that presupposes knowledge of more ancient precedents.

Antiquity

The inception of the Italian Garden is deeply rooted in the Latin world. The Romans, known for their conquests, were adept at assimilating traditions and customs from the cultures they dominated, which they then ingeniously modified and incorporated within their own realms. This cultural amalgamation was evident in their adoption of Hellenic garden practices – what Greeks, originally influenced by Eastern traditions, dedicated to sacred spaces – which the Romans expanded into the domestic sphere.

Roman villas became showcases for various features and advancements that would eventually be passed down to the gardens of the Renaissance. They were laboratories for innovations in hydraulic engineering, the functional and decorative use of trees, and the creation of visual and acoustic enhancements through architectural design.

The Middle Ages

With the fall of the Roman Empire giving way to the medieval period, an era fraught with instability, famines, and invasions emerged. This tumultuous time necessitated a practical approach to the countryside as a means of survival.

However, it is during these centuries that a new interpretation of the garden manifests. The rise of monasticism led to the creation of monastic gardens: serene sanctuaries enclosed by high walls where monks sought divine connection. These enclosed gardens, or hortus conclusus, symbolized a return to the idyllic Eden, representing peace among all beings and serving as a bridge to the heavenly.

The rebirth of the Italian garden was not solely influenced by Christian and agricultural revival. The Arab conquests in southern Italy, along with the ascent of rural nobility and a burgeoning urban middle class, played significant roles characterizing the Italy of municipalities.

The Arabs, with their advanced knowledge of irrigation and cultivation, introduced an array of new plant species to Sicily, such as citrons, oranges, lemons, as well as sugar cane, cotton, dates, and bananas. The linguist Abû Bákr Muhammad even suggested that the name Sicily is a blend of the words Sikah Kîlîyah, which in the rûmi language translate to fig and olive, trees highly esteemed by Muslims. On the Italian mainland, new ideas about the interplay between art and nature spread. New social classes, alongside the established feudal nobility, began to wield their influence beyond the confines of urban centers. The fresco Allegoria del Buono e del Cattivo Governo by Ambrogio Lorenzetti, painted in 1338 in the Palazzo Pubblico of Siena – and now housed in the city’s Museo Civico – prefigures the movement to reclaim and transform the countryside, a vision that would reach its zenith in the Renaissance.

The Renaissance

During the Renaissance, the revival of classical antiquity in the 15th and 16th centuries profoundly influenced the conceptualization of green spaces, shaping the Italian Garden into its current form.

The burgeoning bourgeoisie constructed rural villas were inspired by the rediscovered wisdom of ancient texts, the interpretations offered by contemporary intellectuals, and a rekindled interest in the natural sciences.

Leon Battista Alberti’s mid-15th-century treatise, De re Aedificatoria, laid out the essential principles for villa construction near urban centers, ensuring they were places of both pleasure and profit. Architectural designs aimed to delight with landscapes that included blooming meadows, sunny expanses, shady groves, and clear water features, all in sync with the natural surroundings. These villas also served practical purposes as agricultural hubs, providing sustenance and income to their owners.

Gardens were integral to villas, facilitating leisurely enjoyment of nature. Notably, the Accademia neoplatonica, an intellectual hub established in Florence by philosopher Marsilio Ficino in the latter half of the 15th century, was situated in Cosimo de’ Medici’s Villa di Careggi.

In Tuscany, the Medici family’s villas were instrumental in developing the Italian Garden tradition. In Rome, however, the evolution of garden art is closely associated with villas stemming from papal initiatives. The return of the papacy from Avignon to Rome marked the city’s gradual resurgence to prominence. This renaissance was significantly propelled by Giulio II, the pope from 1503 to 1513, who brought the era’s most celebrated Italian artists to the Vatican, including Michelangelo Buonarroti, Raffaello Sanzio, and Donato Bramante. In the years that followed, other renowned figures like architects Vignola (Jacopo or Giacomo Barozzi), Pirro Ligorio, and sculptor Bartolomeo Ammannati, left their mark. Today, Villa Giulia and Villa Pia still bear the splendid hallmarks of these historical contributions.

Beyond the Renaissance

Following the Renaissance, the evolution of the Italian Garden was less about altering its essence and more about refining its aesthetics, with an emphasis on creating more spectacle and novelty. This era was marked by a paradox in attitudes: while the natural landscape of the garden continued to be appreciated as a means of connecting with nature – a sentiment echoing Renaissance values – the prevailing French influence began to steer the aristocracy away from the rural life that inspired their grounds.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, French and English gardeners admired the Italian approach but ventured into creating their distinct styles, which stood in stark contrast to one another. The French preferred a majestic formalism, while the English embraced a more free-form and picturesque garden layout. This latter style eventually made its way to Italy, inspiring a new garden genre that harmonized with the landscape, ultimately giving rise to what is known as the landscape garden.

Italian Gardens: defining features and elements

The Italian Garden came to fruition during the Renaissance, blossoming from the 15th through the 16th centuries. This novel form of art radiated out from Florence, reaching Rome, and eventually influencing the regal domains of Mantua, Ferrara, and Venice. Adhering to meticulous stylistic principles, many of which endure in the remnants of historical villas.

Defining spaces

During the Renaissance, the organization of space was a deliberate art that applied to both architecture and gardens. The design of gardens followed strict geometric principles, with a main axis leading from the villa’s entrance, intersected by secondary pathways, to form a distinctive orthogonal pattern. The arrangement of avenues and paths was intentional, each with a designated start and end point. There is a search for polarity, the tension of elements, the contrast between light and shadow. A panoramic terrace at one end might be balanced by an intimate grotto at the other. Leon Battista Alberti, a Renaissance humanist, emphasized geometric forms – squares, circles, and semicircles – which were used to create interconnected spaces that seamlessly extended from the villa. The spatial design relied on structural elements like walls featuring niches, orderly rows of trees such as cypresses, yews, boxwoods, and holm oaks, and hedges, which became a prominent feature in the 17th and 18th centuries.

The terrace

In Renaissance gardens, the use of terraced levels marked a departure from the enclosed medieval hortus conclusus. While still framed by walls and hedges, the Italian Garden introduced multiple tiers, crafting open spaces and vantage points that invited the gaze to wander from the villa to the broader landscape. These viewpoints, or belvederes, became integral for appreciating the world’s beauty beyond the garden’s confines. Loggias played a similar role. As Alberti noted: “adding balconies to a house’s facade was a delightful pursuit”. These balconies, or loggias, projected from the exterior walls, offering sweeping views over the gardens and surrounding countryside, and served as favored spots for reflection and observation.

The parterre

Viewed from the elevation of the terrace, it was possible to admire the geometry created with the flower beds, the so-called parterre. These flower beds, typically bordered by boxwood hedges, were meticulously laid out in cruciform patterns, and divided into distinct areas. Their design, starting from simple arrangements and evolving into more elaborate forms, not only served an aesthetic purpose when viewed from above but also added a pleasant volume to the garden. Regrettably, the ornamental use of fruit trees in parterre, once prevalent in early Renaissance gardens, had dwindled by the Baroque era and such examples are no longer seen today.

In place of traditional parterre, structures like the lemon house and orangery were introduced, where citrus trees potted in terracotta were spaced tightly to mimic a grove. Additionally, the labyrinth became particularly popular towards the late 16th century, finding its place not only in Italian gardens but also throughout the gardens of Central and Northern Europe.

The staircase

In the Italian Garden, the staircase is a showcase of diverse shapes and artistic expressions. Pioneered by Bramante at the Vatican Belvedere, it soon became a quintessential feature of Renaissance garden design, reflecting the era’s architectural brilliance. Grand and majestic, these staircases rose to prominence in the 16th century and Baroque gardens, celebrated not just for their visual appeal but also for their theatrical presence. They provided a stunning visual element and served as a stage for social display, offering an ornate journey that elevated the act of ascent to a ceremonial experience.

The pergola

The pergola, a garden feature that is both open and protected, has been a cherished element since ancient times. Draped with climbing, frequently aromatic plants, pergolas provided a delightful sanctuary for strollers, a tradition that continued uninterrupted even through the Middle Ages. Today, the Medici’s Trebbio Castle, a Renaissance gem near Florence, maintains its historical pergola. It stands with its circular columns topped with sandstone capitals, all under a canopy of intertwining vines and roses.

The water

Water features, much like pergolas, have been integral to garden design since ancient times, particularly in Oriental and Greek landscapes. In the Italian Garden, it’s important to distinguish between still and moving water.

Still water is represented by rectangular or circular pools with water emanating from artistically carved conduits, sometimes adorned with water lilies and sculptures of fish and birds. The most elaborate versions include pools resembling small lakes with central islands reached by slender bridges. The Giardino di Boboli in Florence boasts an exquisite example, featuring a pool with an elevated center that accommodates a garden and a fountain.

As for moving water, its variations are manifold:

- Hidden conduits often masked by animal-head sculptures nestled among moss and ferns;

- Fountains where water arcs into the air before cascading down, creating theatrical displays;

- Waterfalls, often paired with staircases, a concept first introduced by Vignola that grew in scale and drama over the centuries;

- Playful water jets, emblematic of the 17th century, showcasing the period’s advanced hydraulic technology and the whimsical spirit of courtly gardens.

Ornamental sculptures

The courtyard beside the Belvedere villa, crafted by Bramante for Pope Giulio II, was pioneering in setting gardens as a stage for art by housing statues from the pontifical collection, like the Apollo del Belvedere and the Gruppo del Laocoonte.

This move not only turned gardens into open-air galleries but also maintained a connection with the Roman practice of using statues to enhance outdoor spaces.

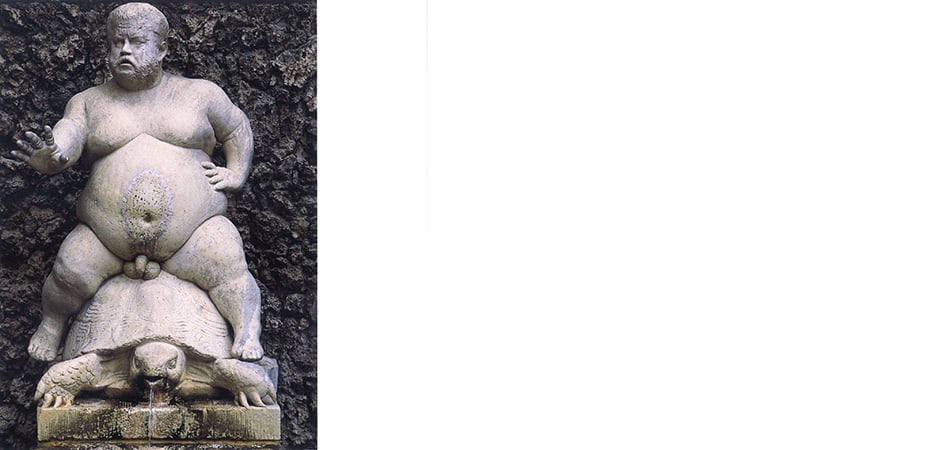

Renaissance gardens favored classical deities like Venere, Flora, Diana, Bacco, river gods, satyrs, and other mythological figures. The Baroque era shifted to embrace more contemporary and courtly themes, depicting musicians, dwarfs, and jesters, with the Nano Morgante in the Giardino di Boboli being a notable example.

The interplay between sculptures, plants, and water features was significant, evolving into more daring and intricate designs in the Mannerist and Baroque periods, with masters like Giambologna, Tribolo, and Bernini leading the way.

Are you interested in articles like this?

Sign up for the newsletter to receive updates and insights from BeCulture!

The grotto

In the Italian Garden, grottoes from the 16th-century Mannerist period are rarely natural formations; they are usually crafted artifices, richly decorated in a variety of styles and sizes. They range from small niches with trickling water and mosaic adornments to large chambers filled with statues. Water runs over surfaces embellished with moss and ferns, as well as natural accretions like tufa, pumice, mosaics, shells, stalactites, crystals, and intricate engravings, creating an opulent yet elegant atmosphere. Pioneering this trend were the grottoes by Buontalenti for Francesco I de’ Medici at Villa Pratolino and the Giardino di Boboli, both iconic sites for 17th and 18th-century grand tour travelers.

The woodland and plants

Offering a contrast to the manicured parterre and serving as a complement to the grotto, woodlands in the Italian Garden were a curated slice of the wild. They offered a sanctuary of coolness and shade. Villa Rizzardi, built in the late 18th century near Verona, still boasts one of the final examples of this garden style, with its elm grove encircling a stunningly beautiful open-air pavilion.

Typical trees like elms, cypresses, pines, holm oaks, plane trees, and maples form the arboreal backbone of these gardens, often joined by Magnolia Grandiflora and cedars in Tuscany, with palms appearing further south. Vines, ivy, and fruit trees add to the mix, with oranges and lemons providing symbolic decorative touches, as seen in Renaissance paintings, notably the Primavera by Botticelli.

The art of topiary, sculpting the foliage of trees, was facilitated by the presence of boxwood, yew, juniper, rosemary, and laurels, typically Mediterranean shrubs. Hydrangeas, azaleas, rhododendrons, camellias, wisterias, and bougainvilleas were introduced later, in the 18th and 19th centuries by the English, sourced from the Far East.

The exact variety of flowers in Renaissance gardens is unclear, but based on artistic and literary records, one could envision roses, violets, cyclamens, white lilies, lily of the valley, carnations, primroses, irises, pansies, daisies, and forget-me-nots.

While modern perspectives and principles have drifted from those that originated and refined the Italian Garden, we still acknowledge their enduring, almost spiritual enrichments. Conversely, today’s gardens also function as public spaces, an idea alien to the Renaissance mindset, with the first public park being St. James Park in London, laid out by John Nash in 1814 – a tale for another time.