Unique and exceptional, Venice is not only a must-see destination for anyone visiting Italy, but also an essential stop for art lovers. It was here that, in the sixteenth century, a new style of painting took shape—one that could rival the Tuscan-Roman school and establish itself firmly in the cultural landscape of the time. Let’s explore the key features and protagonists of the so-called Venetian Renaissance.

Tonal painting and the Venetian Renaissance

At the dawn of the 16th century, Venice was a global maritime power. Trade with the East was flourishing, and expansion beyond the Lagoon continued, albeit with some difficulties. The Republic of Venice and its patrician elite ruled in an atmosphere of peace and prosperity, generously supporting local artists. Political autonomy, economic stability, and multicultural influences provided the ideal conditions for new artistic developments.

Immersed in Venice’s unique atmosphere, with its soft reflections on water, and influenced by Northern European realism, Venetian artists redefined the use of light.

While in the Tuscan and Roman areas drawing and composition were the foundations of figurative representation, Venetian painting placed colour at the centre—giving rise to tonalism. Sensitive to the effects of light on bodies and objects, painters used a technique of glazes—layering lighter or darker shades of the same colour to create spatial depth and three-dimensionality. Colour combinations were carefully and skilfully studied to produce harmonious ensembles and capture atmospheric effects in landscapes. These became a favourite genre, along with portraiture and allegorical themes, which joined the more traditional sacred subjects, never entirely abandoned.

Are you interested in articles like this?

Sign up for the newsletter to receive updates and insights from BeCulture!

The masters of 16th-century Venetian art

At the forefront of this new movement was Giovanni Bellini (1431–1516), one of the first in Italy to master oil painting, a technique that allowed for more precise tonal gradation. From his circle emerged Giorgione and Tiziano—two pivotal figures of the new school.

Nature brought to life in Giorgione’s paintings

Little is known for certain about the life of Giorgio (or Zorzi) da Castelfranco Veneto, known as Giorgione (1477/78–1510), and even the attribution of his works remains a subject of debate. These uncertainties contribute to the aura of mystery surrounding the artist, who, although not a native, was naturalised in Venice, where he found fame and fortune in the early 1500s. Considered the founder of the Venetian school, he came into contact with Bellini and likely also with Leonardo da Vinci, who visited Venice during those years. As Vasari1 suggests, it may well have been Leonardo’s influence that sparked Giorgione’s interest in light and sfumato, which he captured with soft, pure-colour brushstrokes.

Giorgione’s work stood out immediately for both technical and iconographic innovation: in his paintings, landscapes are no longer mere backgrounds but take centre stage. This is evident in the companion panels Mosè sottoposto alla prova del fuoco (1505) and Il Giudizio di Salomone (1505–08), housed in the Gallerie degli Uffizi in Florence—but especially in his Tempesta (1504–09, Venice, Gallerie dell’Accademia). As famous as it is enigmatic, the painting portrays a mother nursing her child in the presence of a young soldier, but the relationship between figures and background is unbalanced, as most of the canvas is taken up by a pastoral setting: the lightning-struck sky gives the painting its title and animates the scene along with the rest of nature. The skilful use of light brings the trees, stream, and distant buildings to life. Numerous interpretations have been proposed, but to this day, the meaning of the work remains elusive.

Tiziano’s vibrant tonalism

Tiziano Vecellio (1485/90–1576), longer-lived and more prolific, was born in Cadore but considered Venice his true home and returned to it whenever he could. His reputation grew swiftly, attracting prestigious commissions from nobles and rulers across Europe. It is even said that Emperor Charles V once stooped to hand him a fallen brush while he was at court.

Tiziano’s extraordinary success lay in his revolutionary style, which followed the path opened by Bellini and advanced by Giorgione, but reached full maturity in his own hands. In his paintings, tonalism is fully expressed—colours shape the figures and render their volume, light, and shadow. Tiziano’s brilliance also lay in his stylistic innovations, such as in the Madonna con santi e membri della famiglia Pesaro (1519–26, Venice, Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari). In this altarpiece, the Madonna does not sit in the centre—as tradition dictated—but on the right, balanced chromatically by the flag held by an armoured soldier. An original and daring choice that demonstrates Tiziano’s ability to overturn conventional schemes while still achieving perfect compositional balance.

Alongside religious themes, Titian also painted mythological subjects—which he called “poesie” (poems)—though his true speciality was portraiture, particularly of women. His naturalistic style is evident in the modelling of bodies, the vibrant skin tones, and seductive gazes, often set in intimate settings. Thus, against the backdrop of an elegant bedroom where two maids are busily at work, the Venere di Urbino (c. 1538, Florence, Uffizi) continues to captivate us with the sensuality of her figure and her flirtatious demeanour; adorned with only a few jewels, her gaze directed at the viewer, she teases our desire.

Tintoretto’s dramatic use of light

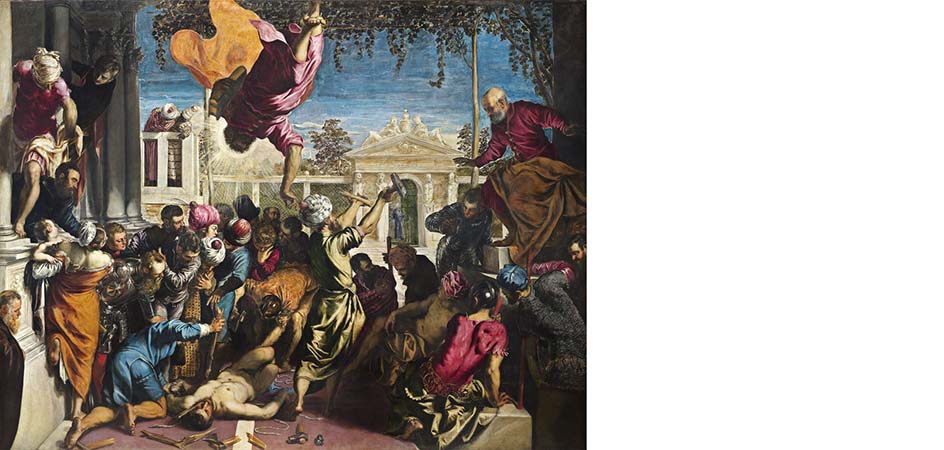

Jacopo Robusti, known as Tintoretto (1518–1594), was born, lived, and died in Venice. Historical documents and biographies have preserved numerous anecdotes about him, including one that claims Tiziano expelled him from his workshop for being too talented. Whether true or not, the story speaks to the magnitude of his talent—clearly seen in his bold yet successful synthesis of Michelangelo-inspired drawing and the colouristic style of Vecellio. Tintoretto was influenced by Mannerist currents of Tuscan-Roman origin, yet he combined them with daring use of light. His figures take on elaborate, emphatic poses, with bodies twisting in elongated spirals typical of the Mannerism style. These whirling torsions are made even more dynamic by his theatrical use of light.

This is evident in the three canvases for the Scuola di San Marco: the Ritrovamento del corpo del Santo (Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera), the Messa in salvo del corpo di San Marco and the Miracolo dello schiavo (both in Venice, Gallerie dell’Accademia), painted between 1562 and 1566. The dramatic scenes—depicting key episodes from the saint’s life—are intensified by their theatrical composition, with exaggerated perspectives and elongated architectural elements. The pronounced plasticity of the figures, arranged as if on a stage, is accentuated by vibrant colours and carefully placed highlights. A stylistic hallmark that defines – albeit with some later softening and developments – the artist’s long career, marked by an ability to engage with his contemporaries as well, such as the refined Veronese.

Veronese’s imaginative sensibility

A successful painter known for his gentle and affable manners, sociable yet composed, Paolo Caliari, known as Veronese (1528–1588), took his name from his native city. After early commissions across the Veneto and Emilia, he entered the Venetian scene, where he quickly won favour with important patrons and fellow artists. Even Tiziano was impressed by his talent. Enthralled by the decoration of the Libreria sansoviniana di San Marco, he deemed him so gifted that he deserved a gold necklace as a reward for his work.

Though influenced by the robust Mannerism of Giulio Romano—architect, painter and one of Raffaello’s collaborators—Veronese tempered its excesses with a serene and measured painting style, serene even in its most imaginative flourishes, defined by a bright, sunlit palette. Instead of strict naturalism, he preferred an idealised vision of reality, also rooted in Mannerism, but always shaped by exceptional chromatic harmony (he was a master of tonal complementarity) and compositional balance. Unlike Tintoretto, Paolo’s works contain no drama or turmoil—they are illusionistic and at times playful representations, reflecting a temperament devoted to vitality and joy.

This is clear in the clever and original frescoes at the Palladian Villa Maser. But today we wish to focus on another painting, exemplary not only of his pictorial language but also of his spirit—free, pure, and sharp: the Convito in casa Levi (1573, Venice, Gallerie dell’Accademia). Painted for the refectory of the convent of Santi Giovanni e Paolo, it replaced a Tiziano’s work that had been sadly destroyed by fire. Originally, it depicted an Ultima Cena, but the figure of Christ, painted inside a contemporary city palace, was deemed inappropriate by the Holy Inquisition because he was surrounded by ‘buffoons, drunken Germans, dwarfs and other obscenities’, as stated in the ruling.

The ecclesiastical tribunal accused Veronese of heresy and ordered him to correct the painting. His response, in both words and actions, is a bold affirmation of his intellectual independence: “We painters take the same licence that poets and madmen take… I paint and compose figures.” In other words, his work was the product of imagination, not a faithful retelling of reality, and thus fully legitimate. Cleverly, instead of altering the painting, Veronese simply changed its title—and therefore its subject—referring to the episode of the Supper at the house of the Pharisee from the Gospel of Luke.

Art always manages to surprise us. Time and again, we marvel at how, even when beginning with similar premises, the outcomes can be so diverse and astonishing—just as they were in 16th-century Venice. It is precisely this variety that makes the history of art—in any era or place—such a fascinating journey, always full of discoveries and new inspiration.

1.Giorgio Vasari (1511–1574), artist, architect and writer at the Medici court, was also the author of Le vite de’ più eccellenti architetti, pittori, et scultori italiani, da Cimabue insino a’ tempi nostri (published in 1550 and expanded in 1568), a foundational text in the history of Italian art.