Throughout the history of Western art, Ugliness has undergone a fascinating evolution. Initially viewed as a mere negation of beauty, it gradually acquired the status of an aesthetic category. This shift in taste and culture makes it even harder to define what is considered beautiful or ugly in art.

We’ve selected a few themes that highlight the concept of ugliness between the 15th and 16th centuries.

A brief historical overview: the concept of ugliness and its transformations through the Centuries

The ancient Greeks, who saw beauty as the expression of physical and moral perfection (as reflected in the famous concept of kalokagathia – “beautiful and good”), were equally obsessed with ugliness. Ugliness interpreted both as wickedness and as physical deformity. Mythological tales abound with the former, while the latter is represented in the rich repertoire of monsters and fantastical creatures that populated the ancient imagination. A renowned example—one we might even describe today as stunningly beautiful! —is the Chimera di Arezzo, created in the early 4th century BCE.

The Renaissance is commonly associated with the ideals of beauty and harmony, and indeed, this period celebrates perfect proportions and mathematical perspective. However, it is also the era of Leonardo’s grotesque heads and Bosch’s visionary works.

Shortly thereafter, Mannerist artists explored and exaggerated the concept of ugliness, partly rejecting the principles of their Renaissance predecessors, while in Caravaggio’s Baroque, we find explicit depictions of a harsh and unappealing reality—all too much so, according to some contemporary critics.

Romanticism, in its pursuit of the Sublime, included elements of terror, awe, and overwhelming power in its representations, capable of stirring intense emotional responses. Later on, artistic movements such as the Macchiaioli distanced themselves even further from idealised depictions, focusing instead on everyday life and ordinary people—including aspects traditionally considered ugly.

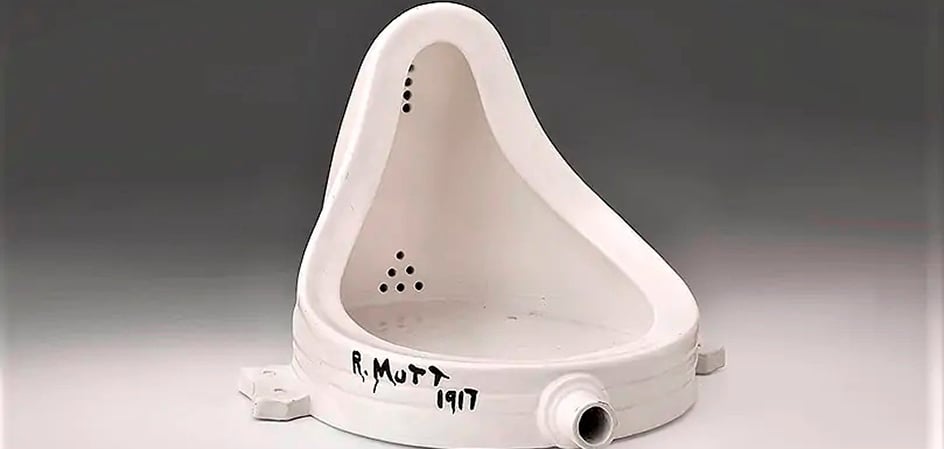

Ugliness takes centre stage in the historical avant-gardes, which challenge prevailing aesthetic norms and social values. One of the most notable was Dada, which rejected artistic conventions and provocatively embraced the grotesque, the absurd, and the intentional ugliness— a quintessential example of this approach is the celebrated ready-made: the orinatoio di Duchamp.

Even this quick overview reveals the complexity and ever-changing nature of this theme – fascinating, vast and deeply subjective.

Death: an inherently ugly subject

Death is, by definition, ugly—and this is how it has been represented across the centuries.

Often represented as a skeleton or an emaciated woman, sometimes with bat wings, on horseback or riding a monster, armed with a scythe—death takes on a terrifying and grotesque appearance. Its image, which often carries a didactic function, was meant to admonish viewers, prompting reflection on the consequences of their actions and the idea of divine justice applying to all.

Are you interested in articles like this?

Sign up for the newsletter to receive updates and insights from BeCulture!

One of the most emblematic depictions is the fresco painted by Giacomo Busca, known as il Borlone, between 1484 and 1485 on the façade of the oratorio dei disciplini in Clusone (Bergamo). In the upper register, we see the trionfo della Morte, crowned and emerging from a sarcophagus in which the head of the Church and the Emperor lie in ceremonial garments. But theirs is no peaceful slumber—they are tormented by symbolic animals: five snakes, symbolising Satan the tempter, and therefore death and corruption; two toads, alluding to pride; and a scorpion, associated with betrayal and heresy. Surrounding them, wealthy men desperately attempt—without success—to buy the favour of the fearsome “Lady” with gifts and prayers, while two armed skeletons spread terror and death. To the left, a hunting party alludes to the legend of the three living and the three dead, a moralising tale popular at the time. Completing the scene in the lower register is the danse macabre, in which each living figure is mirrored by a double in the form of a decomposing corpse—a further chilling reminder of life’s transience.

The old and deformed woman

Ugliness also defines death in Hans Baldung Grien’s painting Le tre età della morte e l’uomo (1541–1544, Madrid, Prado Museum). An obscene creature carrying an hourglass is seen leading an elderly woman, who drags behind a reluctant, sensual young woman and, at their feet lies a dead child. Next to the young body, an owl, symbol of wisdom, warns viewers of the tragic consequences of sin. The only glimmer of hope is the Redeemer, who appears in the background, ascending crucified into the sky.

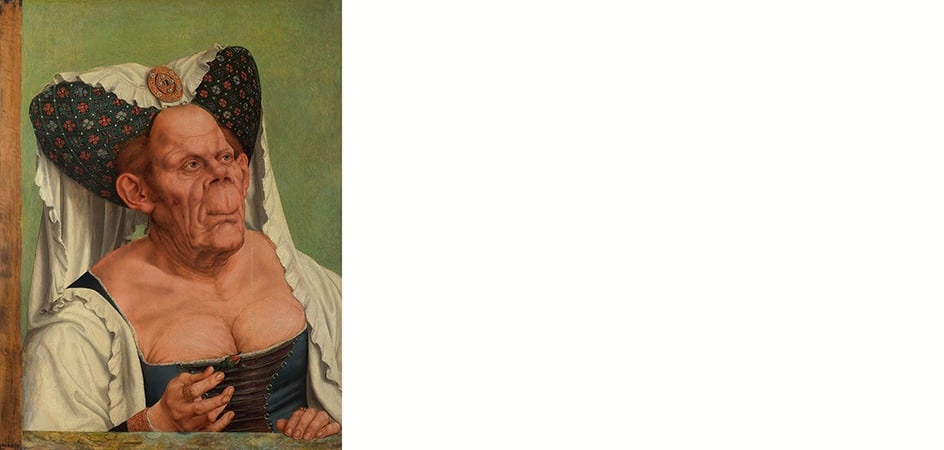

The theme of death intertwines with that of the ugly woman, which art historians say underwent a shift over time: from a symbol of decay in the Middle Ages, the old and unattractive woman becomes an object of curiosity in the Renaissance and even allure in the Baroque. Physical flaws are celebrated as qualities—or at least as signs of expressiveness: stimuli, even sensual ones, preferable to bland classical beauty. No one captured this better than Quentin Metsys. His Donna Anziana, also known as La Duchessa brutta (c.1513, London, National Gallery), boldly asserts the aesthetic value of imperfection. Lively eyes, flared nostrils, wrinkled skin, even a hairy mole and outdated aristocratic attire—all openly defy the aesthetic and moral norms of the time. The work is part of a pair: in the other half, now held in New York, it is shown the face of a man being seduced by the duchess, who coyly holds a rose, symbol of desire. Both portraits are satirical, mocking the vanity of the elderly who try to appear youthful. This painting marks the beginning of the grotesque as a pictorial theme: its author was among the first to introduce secular and caricatured subjects into art.

Hell and the Devil

Alongside death, the devil and hell are also central to the obsessions of artists and devout Catholics. Once again, a clear parallel is drawn between physical and moral ugliness, therefore demons and their Lord are granted terrifying appearances, interpreted in diverse ways.

Among the most horrifying are the Giudizio Universale by Beato Angelico (1430–1435, Florence, Museo di San Marco) and Le tentazioni di Sant’Antonio, attributed to Michelangelo (1487–1489, Fort Worth, Kimbell Art Museum).

In Angelico’s panel, Hell occupies the entire right-hand side. Here, devils with monstrous features— horns, tails, and animal-like limbs— torment damned souls, who are confined in flaming cubicles and subjected to various forms of torture. At the centre-bottom, a black and grotesque Lucifer, with three faces on one head, mercilessly devours bleeding sinners’ bodies, fishing them from a vast cauldron. A truly ghastly scene.

It is said that a young Michelangelo copied real fish to create the demons in his painting now held in Texas. Trained as a painter in the workshop of Domenico Ghirlandaio (c.1449–1494), Michelangelo always preferred sculpture to other arts such as painting, architecture, and even poetry, though he excelled in them.

In Le tentazioni di Sant’Antonio —his earliest known painting—we see the saint lifted into the air during a mystical vision and attacked by demons, yet he withstands their torture. The inspiration came from an engraving by the German master Martin Schongauer (1470–1475, Parma, Fondazione Magnani Rocca). The young Michelangelo was so captivated by it that he reproduced it, adding colour and adapting the composition: he introduced a background landscape and amplified the creatures’ monstrousness with scales and animal traits.

Nowadays, calling the subjects of Michelangelo’s or Beato Angelico’s work “ugly” may seem odd, but this brief survey has shown that artists deliberately embraced formal ugliness to enhance the clarity and impact of their message. To recognise its ugliness, therefore, is to affirm the effectiveness of their art.

The expressive power and allure of the deformed and obscene certainly did not escape later artists and to this day ugliness continues to enjoy a strong – indeed, remarkably enduring – presence.