Ironic, exaggerated, sharp: caricature is, by definition, a controversial art form. The artist strikes where it hurts the most, the subjects portrayed are often offended, and the audience laughs. The history of caricature blends personal, social, and political aspects. In this article, we’ll explore its origins and development in Europe, focusing on some of its most significant figures.

What is caricature?

Caricature is usually a graphic depiction of a person or situation in which flaws or distinctive features are emphasized. The result is ridiculous, paradoxical, and yet incisive: often, the aim is to provoke a bitter laugh, especially when employed as a form of social protest.Not all caricatures serve this purpose, but inevitably, that’s the aspect that made it famous (or infamous) from its earliest days. Despised by the powerful “victims” of its mockery, this art has been opposed, condemned, and censored over time.

A brief history of caricature in Europe

Comic images have been around since antiquity, even appearing on the walls of homes in Rome and Pompeii. In the Middle Ages, depictions of monstrous figures multiplied, and by the 15th; century, there was a marked interest in human features and their deformities – a famous example being the Teste grottesche by Leonardo da Vinci.

These precedents, while important, don’t exactly match what we now call caricature, which only became formalized and defined at the end of the 16th century.

We first hear of “caricatura” with Agostino and Annibale Carracci and their “ritrattini carichi”, so called because they exaggerated and highlighted certain facial features. From that moment on, caricature was cemented in both language and practice. Among its 17th century proponents was Gian Lorenzo Bernini, who produced several caricatures, including one of Pope Innocent XI.

Even though caricature began in Italy, it found especially fertile ground in 18th century England – initially thanks to foreign printmakers, and then through a thriving local tradition tied to political satire. Leading names include William Hogarth, Thomas Rowlandson, and James Gillray.

English caricatures of that period were quite expensive, meant for the drawing rooms of wealthy aristocrats who treated them like valuable curiosities. However, with advances in technology, caricature was democratized: output grew, costs went down, and subject matter expanded to include not only politics but also social satire and amusing domestic or romantic scenes. Printmakers’ workshops became gathering places: displayed in shop windows for sale, caricatures drew in crowds of new potential buyers, including those from lower social classes.

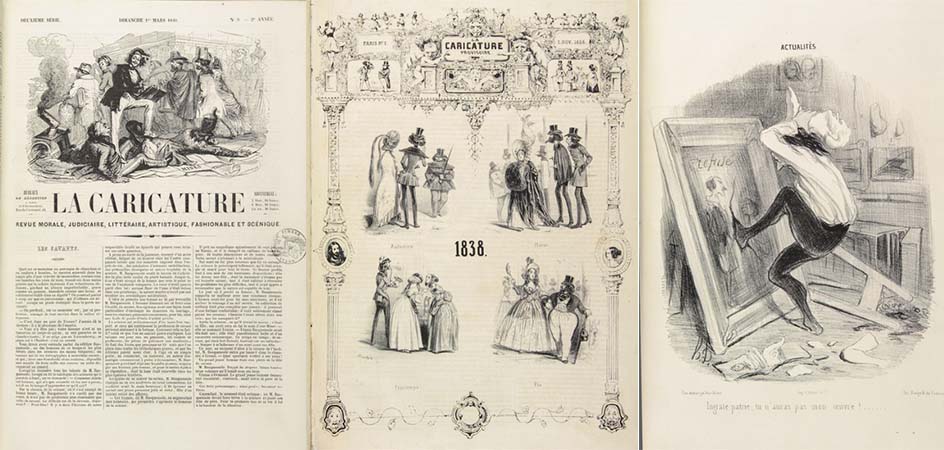

It was in the 19th century that caricature truly took center stage, thanks to the rise of humorous periodicals that spread across Europe. In Paris, Charles Philipon (1800–1862) created the first satirical newspaper, La Caricature, featuring the renowned Honoré Daumier. Other publications soon followed, such as Le Charivari and Le Rire, as well as Punch (in England) and, in Italy, Il Fischietto, Il Lampione, Arlecchino, L’Asino, just to name a few. During the Belle Époque and with the rise of cafés and cabarets frequented by artists and intellectuals, caricature enjoyed its golden age, bolstered by major figures like Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Caran d’Ache (pseudonym of Emmanuel Poiré).As the new century approached, mainstream newspapers also began to show an interest in caricature: satirical cartoons appeared more frequently in daily papers, and more caricaturists were hired by large editorial staffs, leaving the specialized periodicals behind. This gradual shift led to a decline in independent satirical publishing, but caricature—now evolved in various ways—continued to thrive.

The Macchiaioli experience

In Italy, caricature intertwined with the success of the Macchiaioli, a group of artists active in the second half of the 19th century who shared a revolutionary spirit and novel painting techniques. The Caffè Michelangelo in Florence became their meeting point, animated by writers and artists in a lively, carefree atmosphere. Leading figures in this cultural ferment included Signorini, Lega, Palizzi, Moricci, Senesi, Tricca, and Cecioni – well-known exponents of the Macchia style and caricature.

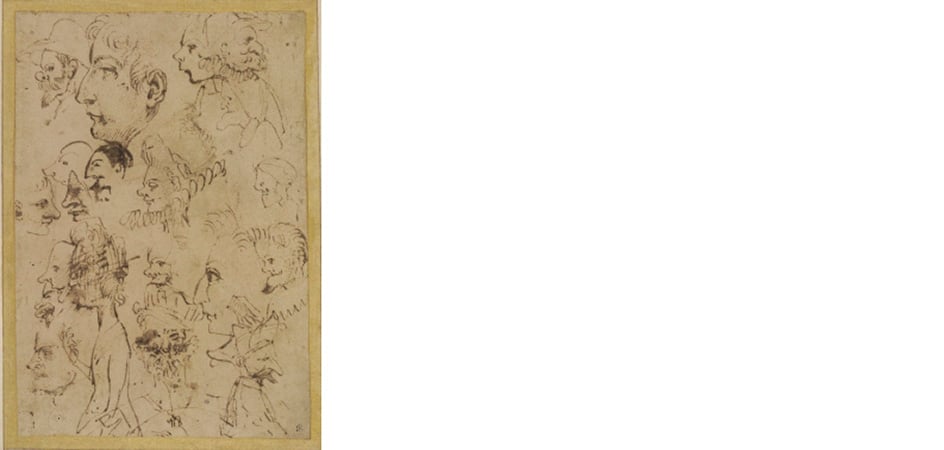

Cecioni, who produced caricatures both in sculpture and on paper, was responsible for the famous illustration of the Florentine café depicting the distorted faces of 24 artists – a portrayal that is both cruel and comical, capturing his fellow adventurers in a single image

3 fun facts about caricature

Having summarized the history of caricature in Europe and highlighted some of the key players, let’s look at a few intriguing and lesser-known facts. We’ve picked three.

A question of technique

The first concerns the technical innovations underpinning caricature’s growth. Throughout most of the 18th century, caricatures were engraved on copper or wood plates, a slow process that made them expensive and limited to a small number of copies.

It was Aloys Senefelder, a broke actor and poet from Prague, who—while searching for a cheap way to print his own poetry at the end of the 18th century—accidentally discovered what became known as lithography. Printing chemically on stone allowed for larger print runs and cheaper copies, substantially contributing to the widespread popularity of caricature.

The next major leap came nearly a hundred years later, in 1872, when both Paris and Turin tried out zincography (relief engraving on zinc plates), which enabled faster, more precise reproduction of original drawings in bigger quantities. Caricature was unleashed.

Are you interested in articles like this?

Sign up for the newsletter to receive updates and insights from BeCulture!

The pear king

The first to harness lithography’s potential for regular periodicals was the Frenchman Charles Philipon, best known for his irreverence toward King Luigi Filippo. Legend has it that while peeling a pear, Philipon noticed its resemblance to the monarch. From then on, depictions of the king as a pear spread far and wide, and Philipon ended up in court for his outrage. He was sentenced to six years in prison and a 2,000-franc fine but managed to get away with far less. How? By showing the judges four drawings illustrating, through progressive simplification, the figure of Luigi Filippo. The last one looked just like a pear. Therefore, argued the cunning Philipon, if the court convicted him, they’d be convicting a piece of fruit. Amid general laughter, he was acquitted but still fined 6,000 francs (instead of the original 2,000). He paid off his debt by selling prints of that very sheet.

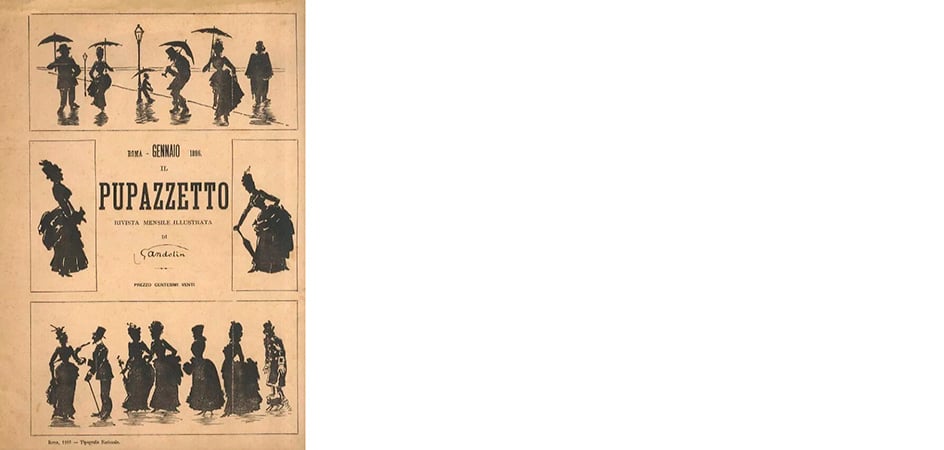

Italy’s Pupazzetti

In 1886, the first issue of Il pupazzetto was published in Rome, a humorous magazine created by Gandolin (the pseudonym of Luigi Arnaldo Vassallo). Thus, a new style of caricature illustration emerged, known as pupazzettismo, characterized by minimal line work reminiscent of children’s drawings and 18th century French silhouettes.

Besides Gandolin, other notable pupazzettari – as they were called – included Yambo, Vamba, and Montani.

Vamba, born Luigi Bertelli, also gave life to an unforgettable character who remains well-known to this day: Giannino Stoppani, nicknamed Gian Burrasca for his unruly, troublemaking nature. His adventures appeared in Il Giornalino della Domenica before being compiled into one volume, Il giornalino di Gian Burrasca, first published in 1912 and still available in bookstores today.

Whether it portrays a politician, a monarch, or scenes from everyday life, caricature has never lost its humorous and corrosive edge since its inception – and perhaps that very quality has made it so irresistible, sometimes dangerous, and undeniably immortal.

Recent tragic events, such as the 2015 attack on the French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo (which resulted in 12 deaths and several injuries), demonstrate the continuing power of caricature even today.