In Florence’s Galleria degli Uffizi, nestled on the second floor amidst the Medieval and Renaissance collections, lies one of the most enigmatic treasures of Western art – Primavera by Sandro Botticelli, dated between 1445 and 1510. This piece, a must-see at the Galleria degli Uffizi, shares wall space with other works by Botticelli, commanding attention not only through its sheer size and life-sized depictions but also through the refined elegance of its subjects, the symphonic arrangement of its characters, and its vivid, detailed portrayal of nature. Visitors transitioning from the galleries featuring art of the 13th and 14th centuries find themselves captivated by the intimate and magical world Botticelli creates.

The iconography, historical context, and various interpretations of Primavera have sparked extensive scholarly debate, with its critical reception ebbing and flowing over time. Let’s delve into what lies within and behind this magnificent panel.

Iconography of the Primavera: what the painting represents

“In the city, he crafted circular paintings with his own hands, many depicting nude women; of which still today at Castello, the villa of Duke Cosimo, there stand two figure paintings. One portrays Venere’s birth, with breezes and winds escorting her to the earth among Cupids; another depicts Venere, adorned with flowers by the Grazie, symbolizing Spring – both rendered with his characteristic elegance.” These are the words of Giorgio Vasari, providing our earliest account of Primavera by Botticelli.

In his 1550 edition of Vite, Vasari describes two paintings – The Nascita di Venere and The Allegoria della Primavera – which, at the time, adorned the Castello villa of Duke Cosimo de’ Medici.

His account, though not entirely accurate (as the god of Love is absent in the Nascita di Venere and only appears in Primavera), is valuable. It provides initial insights into the subjects of the paintings and has helped to establish the enduring name of the work.

So, what is Primavera about?

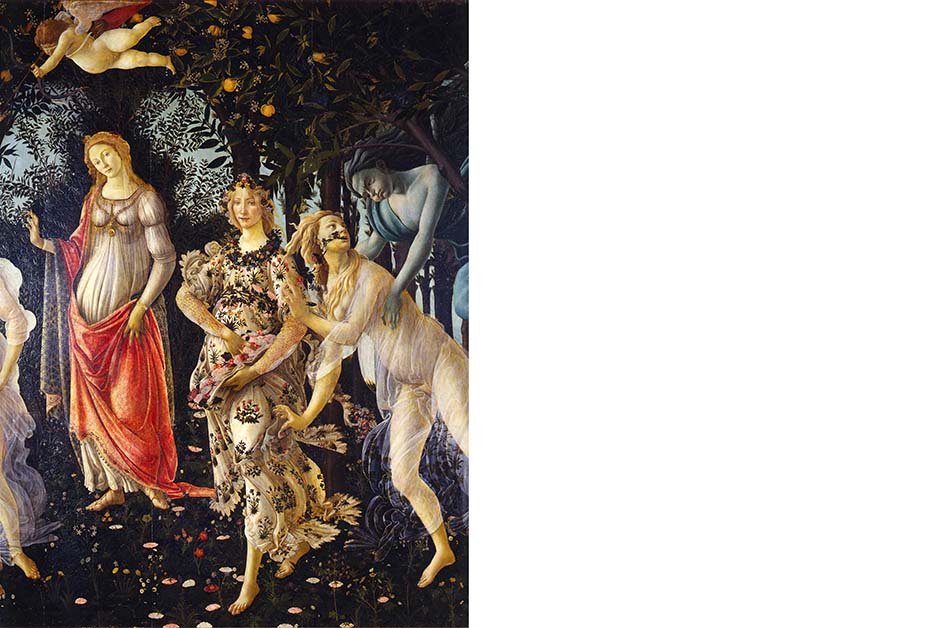

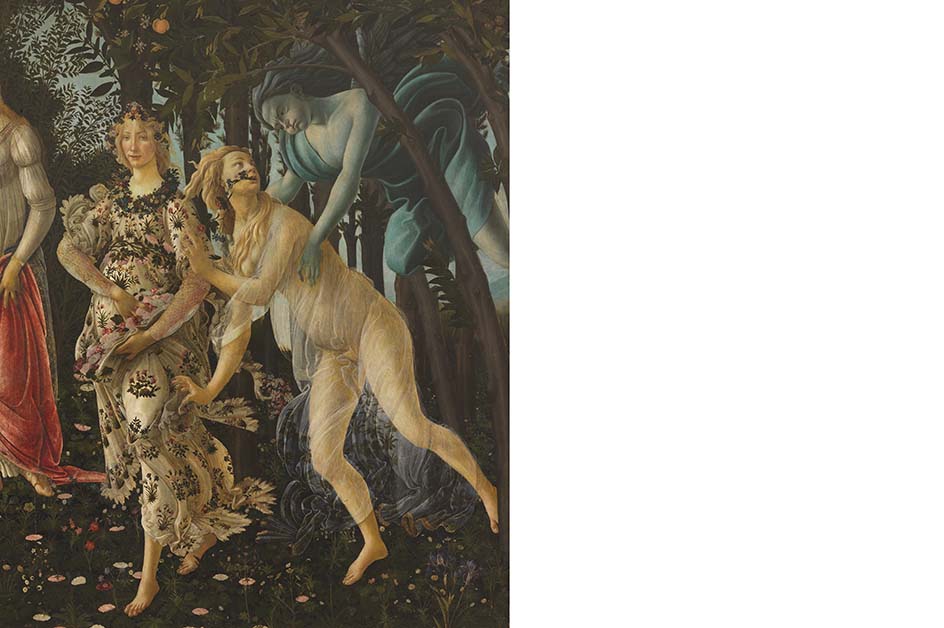

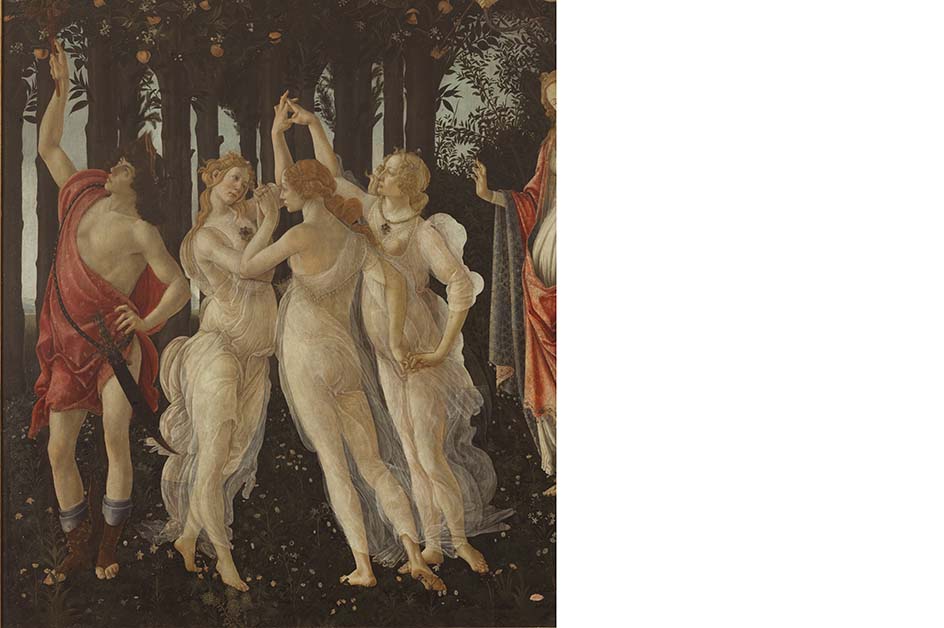

Spanning over two meters in height and three meters in length, the painting invites us into a meadow scattered with flowers and surrounded by a dense orange grove. Nine figures are almost perfectly aligned in the foreground. In a central, slightly recessed position, an elegantly attired woman adorned with jewels meets the viewer’s gaze, her head gently tilted, hand raised in a gesture of welcome. Hovering above her, a blindfolded, winged cherub takes aim with a fiery arrow at three transparently veiled women dancing with intertwined hands. To their left, a pensive young man reaches out toward a cloud. On the painting’s far side, a blue male figure with billowing cheeks restrains a fleeing semi-nude woman who glances back at him as flowers spill from her mouth. Beside her, a pregnant woman in a floral dress seems to be scattering flower buds around.

Through their postures, attributes, and the wealth of historical and artistic references, the figures have been identified. From right to left, we encounter Zefiro, the harbinger of spring, who pursues the nymph Clori, impregnating her and transforming her into Flora, the goddess of blossoms who, pregnant, scatters the bounty of spring. Slightly behind her on her right, Venere, the goddess of beauty, oversees the scene, with Cupido poised above, arrow at the ready.

Beyond Venus, the three veiled Grazie (Eufrosine, Aglae, and Talìa) dance undisturbed, while Mercurio, the winged messenger of the gods, lifts his staff skyward to clear a cloud, seemingly oblivious to the drama unfolding behind him.

Despite the composition’s remarkable equilibrium, there is a noticeable lack of interaction among the various characters, except for the three Grazie and the pair of Zefiro and Clori. This distinct detachment has not gone unnoticed by scholars and has led to a multitude of critical interpretations.

While there is consensus on the iconography (with Venere reigning over a grove populated by various mythological beings), interpretations of the painting vary greatly. These depend, in part, on the different dates ascribed to the work by various historians.

Origin and commissioning: an intricate history

As is the case with many artworks, tracing their origins is not at all straightforward. Sparse records have left us with an uncertain timeline, prompting historians like Ernst H. Gombrich to estimate its creation to be between 1477 and 1478. It was during this period that Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici, the man for whom the piece was likely intended, had just acquired the Castello villa, the same place where Vasari would later encounter the artwork.

Presently, there is a shared agreement among scholars to date the Primavera, alternatively known as Giardino delle Esperidi o di Atlante, to around the year 1480. While the painting is not listed in the 1494 inventory of the country residence, it is noted in the 1498 inventory of Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco’s townhouse on via Larga (now via Cavour) in Florence.

This inventory describes “a wooden painting positioned above the bed, depicting nine figures of women and men”. Adjacent to it, another Botticelli piece, Pallade e il centauro, which resides today in the Galleria degli Uffizi, was likely displayed. The assumed closeness of these two works has sparked speculation about potential political motivations behind Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici‘s commissioning of Primavera from Botticelli.

Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco, along with his brother Giovanni, was part of the family’s younger branch. Marginalized from the governmental affairs of the city, he found himself in constant financial disputes with the senior branch of the family, including his cousins Lorenzo il Magnifico and Giuliano de’ Medici. Following a financial debacle that entangled il Magnifico, the younger Lorenzo took over the Medici villa at Castello. Portrayed as young, educated, and by his own admission, quick-tempered, Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco is today considered the most probable patron, though not definitively confirmed, of the Allegoria by Botticelli.

What Primavera means: diverse interpretations

“Panofsky noted that Primavera is among the select artworks that continue to be interpreted as long as art historians exist”. This observation, highlighted in Horst Bredekamp’s essay on Botticelli’s panel, encapsulates the challenges faced by critics in pinpointing a definitive interpretation of Primavera.

Moreover, Panofsky elaborates in his book Rinascimento e rinascenze nell’arte occidentale that “it is noteworthy that […] the most substantial interpretations tend to be complementary rather than mutually exclusive.”

With this in mind, let’s explore some of the most compelling interpretations that surround this iconic piece.

Literary origins

Some scholars, notably Aby Warburg, suggest that Primavera draws from literary sources, particularly from the poem Stanza by Agnolo Poliziano that celebrates Giuliano de’ Medici’s tournament. Poliziano, inspired by classical writers like Orazio, Ovidio, Virgilio, and especially Lucrezio, crafted imagery that resonates with the characters Botticelli later painted. It’s thought that Poliziano himself might have pointed Botticelli to these literary works as a muse. In the painting, Venere reigns as the goddess of beauty within the domain of Amore, symbolizing Nature and the fecundity of spring. The three Grazie represent a dance between indulgence and purity, giving rise to beauty. The dynamic of chase and allure is captured between Zefiro and Clori; the nymph turns back to her chaser, hinting at a dual pull of attraction. Their encounter ushers in the essence of Spring, personified by Flora.

Philosophical and cultural roots

The interpretation of Primavera extends beyond the literary dimension. It’s critical to acknowledge the young Medici’s ties to the Neoplatonic philosophy championed by Marsilio Ficino, Naldo Naldi, and Giorgio Antonio Vespucci, who were mentors to Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco.

This Neoplatonic ideology, with its educational aims, likely shaped the selection and sequence of figures in the painting. In line with this thought, Primavera by Botticelli is thought to represent the path to moral and intellectual elevation that Ficino prescribed for his pupil. The narrative unfolds from right to left, beginning with base instincts (Zefiro abducting Clori), progressing through romantic and thoughtful Amore (Cupido aiming at Venere), advancing to the virtuous cycle of the three Grazie (emblems of benevolence, reciprocation, and generosity), and reaching its peak with Mercurio, who embodies the pinnacle of intellectual achievement.

Are you interested in articles like this?

Sign up for the newsletter to receive updates and insights from BeCulture!

Political underpinnings

The Allegoria della Primavera may well serve as a canvas for the Medici family’s internal power struggles. The allusions are manifold, from the fiery motifs on the robes of Venere and Mercurio, which were emblems of Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco, to the laurel bushes (laurus in Latin, hinting at the name Lorenzo), and even the orange fruits, symbolically linked to the Medici (mala medica).

In commissioning this piece, Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco might have been declaring his desire to prevail over his cousinin the political and administrative spheres of the city. The depiction of Flora, who embodies Florence itself (Florentia), and the setting of the painting reinforce this theory. Consequently, Venere’s grove, brimming with love and lushness, represents a metaphorical and aspirational site of political resurgence and flourishing. This intriguing argument also posits a revised timeframe for the artwork’s completion, suggesting it was around 1489/90.

The Marriage

Lastly, it is worth considering the interpretation of Primavera as a nuptial metaphor, celebrating the union of Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco with Semiramide d’Appiano, belonging to the nobility of Elba and Piombino.

The wedding took place in 1482 and might have provided the context for the artwork, even if it wasn’t the original muse. Some scholars suggest the painting initially commemorated the romantic encounters of Giuliano de’ Medici, brother to Lorenzo il Magnifico, with a lady named Fioretta, whom he depicted as Flora. After Giuliano’s death in the Pazzi conspiracy, Botticelli is thought to have possibly altered the iconography and repurposed the work for a different patron.

Curiosities and the changing fortunes of Primavera

While these are some of the most substantiated interpretations, the body of analysis surrounding Primavera is ever-growing, with new perspectives emerging in a flourish of theories that mirror the work’s theme and title.

On the topic of flora, it may come as a surprise that Botticelli intricately included no fewer than 138 species of flowers in Primavera, each rendered with remarkable precision and clarity. A myriad of blossoms such as violets, jasmines, irises, roses, daisies, and cornflowers form a vivid tapestry against the meadow’s dark backdrop: why not have fun discovering all of them, perhaps during a visit to the museum with children?

The captivating beauty of Primavera at the Galleria degli Uffizi today can also be attributed to the detailed restoration by the Opificio delle Pietre Dure and the Laboratori di restauro of Florence, completed in 1982. This restoration brought back the original hues of the artwork, previously obscured by a yellowish varnish from past restorations. It also provided insights into Botticelli’s creative process, revealing that he painted nearly all the figures initially, with Clori and perhaps Zefiro added later, followed by the lush vegetation – a fascinating glimpse into the artist’s reflective approach.

However, it wasn’t until the mid-19th century, with a nudge from British academics, that Botticelli’s genius was reappraised. The Pre-Raffaelliti (as they came to be known), disenchanted with academic conventions and the High Renaissance stylings of Raffaello, championed Botticelli’s more “primitive” aesthetic. So much so that in 1880, Dante Gabriel Rossetti was moved to write a sonnet in honor of Primavera after encountering a replica. Until then, Botticelli and his masterpieces had been nearly forgotten; Primavera, once consigned to the Castello villa, only made its way to the Galleria degli Uffizi in 1815 and had to bide its time before receiving the acclaim and recognition that now render it among the most iconic and cherished paintings in the annals of art.