Among the unique works of high Tuscan craftsmanship is the art of hard stones, realized through the creation of pieces in commesso or Florentine mosaic. A tradition that established itself in the 16th century, leaving us enchanting examples of unsurpassed mastery and originality that endure to this day.

But how did this art originate and evolve? And with which techniques? Let’s explore together.

The Florentine commesso: historical overview

The working of hard stones dates back to ancient Greece and Rome, when gems and lapidary materials were carved to create precious cameos or inlaid to decorate walls and floors.

The architectural cladding with mosaics of polychrome marble slabs “commesse” (that is, profiled and juxtaposed to form a geometric design) is known as opus sectile and persisted throughout the Christian era.

However, traces of it were almost entirely lost during the Middle Ages, at least until the Renaissance. In the 16th century, spurred by a general antiquarian rediscovery, the tradition of commesso was revived, especially appreciated by the papal court.

A capital of taste and a magnet for the most important artistic talents of the 16th century, Rome held the primacy in enhancing lapidary mosaics. Yet it was Florence that stood out on the Italian and European scene for working with precious stones. Cosimo I de’ Medici, Duke of Florence, had already dedicated a workshop to it within the new residence of Palazzo Vecchio. Francesco I continued his father’s work both as a collector and as a patron, inviting some of the most famous artisans of the time to the city.

But it was under Ferdinando I (Cosimo’s second son who succeeded his brother) that the Florentine commesso established itself as an absolute excellence. As a cardinal in Rome, Ferdinando had the opportunity to “get hands-on” with Capitoline arts, including those of hard stones, and upon becoming Grand Duke of Tuscany, he brought illustrious examples and authors to Florence.

From this moment on, the Florentine mosaic followed a brilliant, standalone history.

The Opificio delle Pietre Dure: the first institutional workshop

In Florence, in 1588, Ferdinando I de’ Medici founded the first Manifattura “di Stato” (today’s Opificio delle Pietre Dure), immediately engaged in creating the architectural decorations of the Cappella dei Principi in the Basilica di San Lorenzo in Florence: a family mausoleum intended to be completely clad in lapidary inlays. The project was so lavish that it fueled rumors and gossip: according to some, the Medici even wanted to transport the Santo Sepolcro from Jerusalem to here.

Active for over three centuries, the Manifattura followed the political and family vicissitudes of the Medici and, subsequently, the Lorraine, opening (for some years in the 18th century) to elite patrons outside the ducal family.

This long period concluded with the musealization of the Opificio delle Pietre Dure’s collection in 1882 and its transformation – thanks to the visionary Edoardo Marchionni (the Opificio’s first director) – from an artistic workshop to a restoration center, still active and fundamental for the conservation of works from all over the world.

Characteristics and illustrious examples of the Florentine Mosaic

Such a prolonged production could not help but undergo changes in taste and adapt to the styles of each era. We have selected examples that best describe the evolution of the Florentine mosaic, demonstrating its extraordinary vibrancy and variety before it ceased entirely at the end of the 19th century.

The geometric motifs and arabesque decoration of Giorgio Vasari

In its initial phases, the Florentine commesso mirrored Roman compositions, mainly featuring geometric and amorphous figures.

Around the mid-16th century, alongside architectural cladding, a new type of furnishing emerged: inlaid tabletops. Extremely luxurious, they were often created by reusing ancient marbles and stones, abundant in Rome at the time and sought after by collectors throughout Europe.

During this period, Vasari – an artist, historian, and architect trusted by the Medici – made many trips to Rome with the intent of supplying Cosimo I with precious stones and informing him about their use.

It was precisely in these years that he designed his first commesso table, destined for the Florentine banker Bindo Altoviti – the same portrayed by Raffaello (c. 1515, Washington, National Gallery of Art) – and today likely identifiable with the one preserved at the Banca di Roma.

Crafted by the skilled hands of Bernardino di Porfirio, an intagliatore close to the Medici court, “the octagon of jaspers inlaid in ebony and ivory,” as Vasari himself described it, represents a unique piece in stone decoration. It is, in fact, the only known example of moresca (an arabesque geometric motif); more common were sequences of cartouches and medallions of classical derivation, confirming the 16th-century interest in Oriental art. The intricate pattern radiating from the center to the edges is exquisitely drawn by ivory tracing lines and shapes on the dark wooden background, alternating with inlays of Sicilian jaspers.

The pictorial turn and the beginning of a flourishing tradition

Besides founding the Tuscan manifattura (known as the Galleria dei Lavori), Ferdinando I also had the merit of renewing the genre of Florentine commesso by imparting that pictorial character – never again abandoned – that would make it famous.

From this moment on, abstract ornaments were joined by zoomorphic, vegetal, and anthropomorphic figures, well-suited to the illusionistic push of Mannerism and the search for maximum expressiveness in art promoted by the Counter-Reformation.

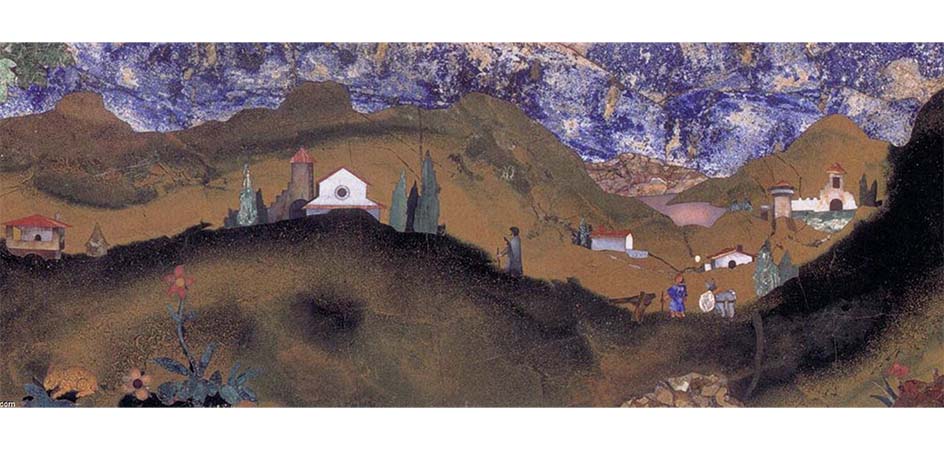

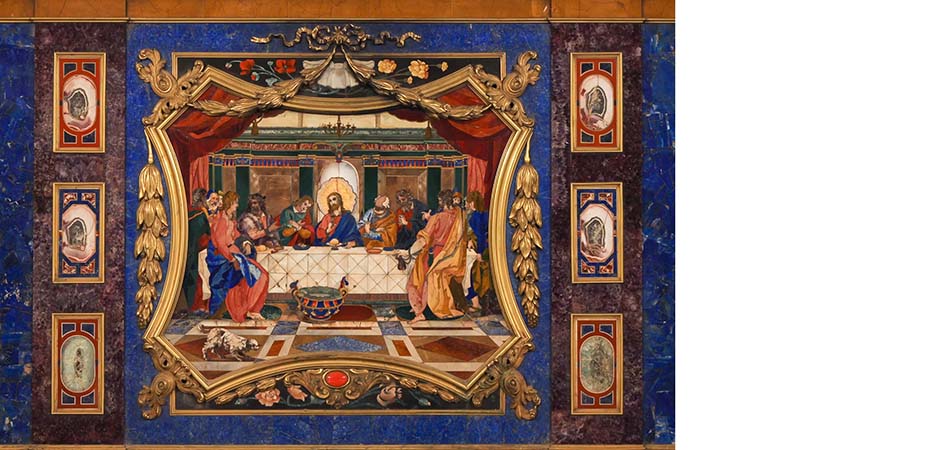

Proof of the skill achieved by master artisans in this era are the scenes depicted in the panels with Paesaggio toscano (Florence, Museum of the Opificio delle Pietre Dure), created in 1608 based on a design by painter Bernardino Poccetti for the altar of the Cappella dei Principi; and in the panel with the Ultima Cena based on a drawing by Ludovico Cardi known as Il Cigoli (1604-1606, modified in 1785, now in the Cappella Palatina of Florence).

Meticulous detail and excellent graphic qualities are emphasized here by the chromatic tones of the stones: agates, lapis lazuli, jaspers, amethyst quartz, and oriental chalcedony are wisely chosen and positioned to compose the scene. The selection was entrusted to the same painters who collaborated with the Florentine Manifattura, tasked with “finding the spots of hard stones” most suitable, to use the words of the 17th-century historian Filippo Baldinucci. Even at the end of the 18th century, the two roles coincided, and those who painted the models for the commessi also had the role of “stone chooser.”

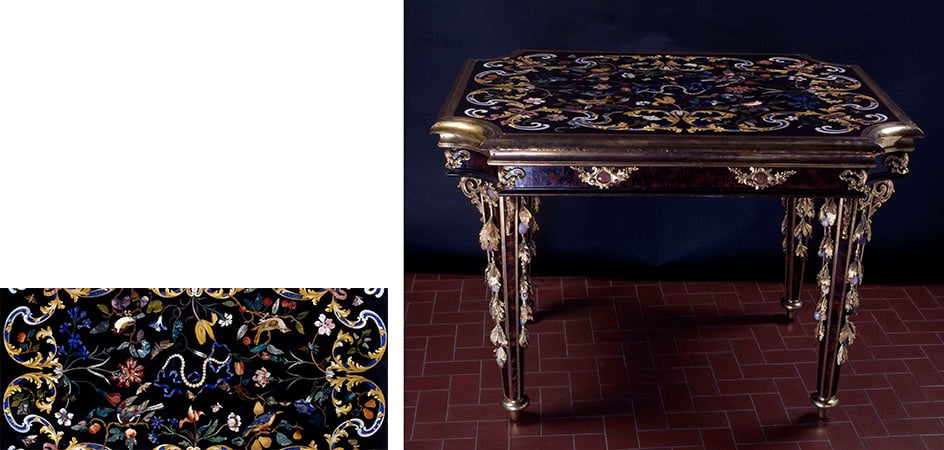

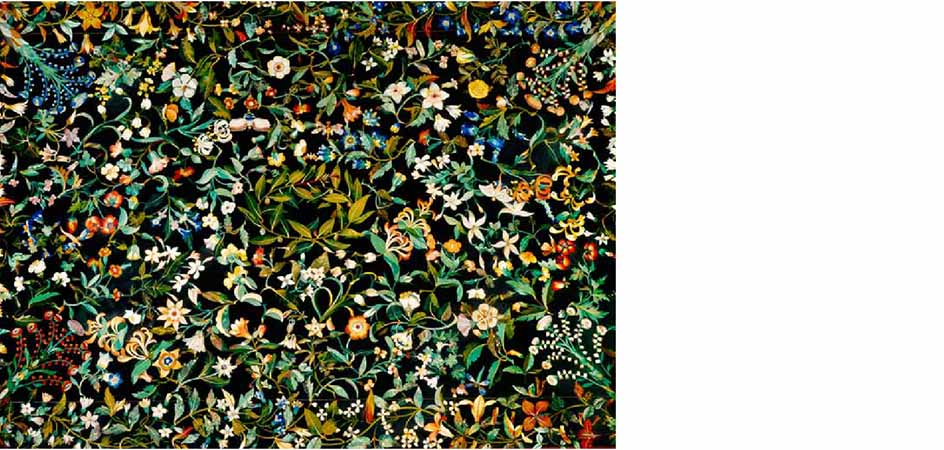

Slightly later and equally magnificent are the two Florentine mosaics with floral themes now housed in the Uffizi: the Tavola dei fiori “sparti” (1614-1621, based on a design by Jacopo Ligozzi) and the Tavolo della Tribuna, initiated to celebrate the marriage between Ferdinando II de’ Medici and Vittoria della Rovere and completed after sixteen years of work (1633-1649). In both cases, the dark background contributes to the exaltation of the vibrant lapidary tones that compose the suggestive tangle of leaves, flowers, grotesques, vases, and animals.

A new turn: allegories and still life

In 1748, the French goldsmith Louis Siriès was appointed director of the Manifattura and implemented a renewal of the artistic repertoire, which had been focused on flowers and grotesques for a century, promoting genre scenes, landscapes, and allegorical subjects.

To achieve this, he turned to the Florentine painter Giuseppe Zocchi, who embarked on a fruitful collaboration with the Manifattura. The works produced from his models were intended to supply the palazzo viennese of Francesco Stefano of Lorraine, the new ruler of Florence, and reflect the new line and classicist taste of Siriès.

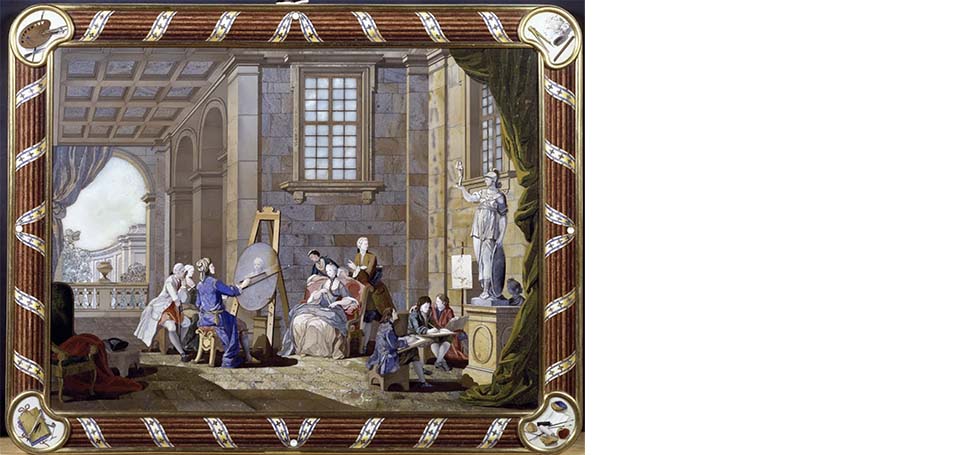

This taste emerges clearly in La Pittura, from the series dedicated to the allegory of the four Arts (1780, Florence, Museo dell’Opificio delle Pietre Dure).

It’s interesting to note the distance between Zocchi’s sketch and the final result. While the former presents a typical scene from an artist’s studio – with jars, hanging mannequins, and piled easels – none of this appears in the commesso version, to which the director had imparted his decidedly more solemn and celebratory vision. More orderly than Zocchi’s drawing, the mosaic does not disappoint and demonstrates the ability of the painter and the executors, brilliantly summarizing the achievements of 18th-century lapidary art.

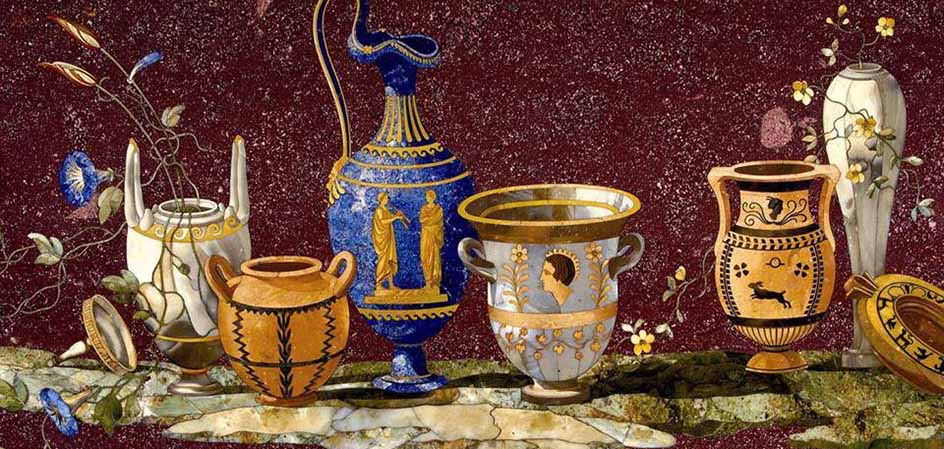

To further demonstrate the versatility of this technique, always ready to renew and update itself, we mention one last example that stands out for detail and refinement: the Piano di tavolo in porfido, con composizione di vasi antichi, executed by the Manifattura in 1784 based on a model by Antonio Cioci (in the Galleria Palatina of Florence). Having taken Zocchi’s place, Cioci masterfully interpreted the new artistic direction of Luigi Siriès (grandson of Louis and son of Cosimo Siriès, also a director of the Manifattura), which required a shift from ambiented scenes to neoclassical still life.

A rigorous composition, exalted by the purity of the materials among which the antique red porphyry of the background stands out – always present in the production of the Florentine commesso and particularly appreciated in the Neoclassical period.

Are you interested in articles like this?

Sign up for the newsletter to receive updates and insights from BeCulture!

The technique of florentine commesso

But how was the Florentine commesso produced? The first step was creating the model, that is, the drawing – oil on canvas or watercolor on paper – made by a painter at a 1:1 scale.

The drawing was then entrusted to the master lapidary and, if it was a very large work, divided among several workers to speed up execution times, which were inevitably quite long.

From the drawing, the master derived a tracing with the division of the pictorial model into many paper “masks,” the subsequent stone sections. This operation was very delicate because the number and shape of the sections directly influenced the final result.

Equally important and laborious was the next phase: choosing the stones and the most suitable “faces,” in terms of colors and shades, to occupy the indicated portion.

Once selected, the stone “slices” (cut to a thickness of 2-4 mm) had to be shaped into the form given by each section. To do this, the corresponding paper mask was applied on top of each one, which would serve as a guide for cutting.

The tools used at this stage were – as then as they are today – very simple, almost rudimentary: a wooden workbench equipped with a vise and a saw composed of a curved chestnut twig and a soft iron wire. Once the stone slab was secured vertically within the vise, the artisan proceeded to slowly cut it according to the predetermined shape, alternating each movement with the passage of an abrasive powder (emery) using a spatula. The combined action of the wire and emery allowed the slab to be cut, which required more or less time depending on the hardness of the material.

The same procedure was followed for the background (if provided), simply making an initial hole that allowed the iron wire to pass through and start the cut.

To achieve an impeccable result, it was necessary for the profiles of each section and the background to match perfectly: only then was it possible to bring them close to each other without visible gaps, like a puzzle. When everything was in place, the composition was turned over, and the pieces were glued together.

The final phases of smoothing and polishing gave the work its finished and brilliant appearance.

A laborious and fascinating technique that amazes for the simplicity of its tools but – as we have seen – produces results of enchanting finesse. If we have piqued your curiosity and you want to see the process of Florentine commesso up close, you just need to plan a visit to the Museo dell’Opificio delle Pietre Dure and its workshop, where you can also observe some of the oldest and most renowned examples of this marvelous tradition.