Few authors have inspired artists of the calibre of Giotto, Botticelli, Raffaello and Michelangelo as much as Dante Alighieri (1265–1321), still world-renowned for his Divina Commedia. A man of prose and poetry, Dante was forced to leave his native Florence due to political strife. Yet the city still preserves many traces of his enduring fame.Like a modern-day Virgil, we will guide you through the halls of the Gallerie degli Uffizi to discover some of the most evocative works linked to the Supreme Poet and his words.

Dante: a man of his time

Although he lived between the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, much is known about Dante’s life thanks to numerous written accounts – his own, as well as those of contemporary or later authors – and also through visual representations by artists across the ages, which have become part of our collective iconographic heritage.

The portrait of Dante

Today, we all recognise Dante’s features: a clean-shaven face, aquiline nose, red hood and robe, often with a laurel wreath. This iconic image was first fixed by Giotto (or his school) on the walls of the Bargello. Its rediscovery in 1840 prompted the people of Florence to transform the old palace into the present-day Museo Nazionale.

The image of Dante, corroborated by literary descriptions, thus became a recurring theme in art history. Notable examples include Luca Signorelli’s frescoes (1499–1504) in San Brizio (Orvieto), those in the Stanze by Raffaello (1508–1524) at the Musei Vaticani, and of course, those housed at the Uffizi.

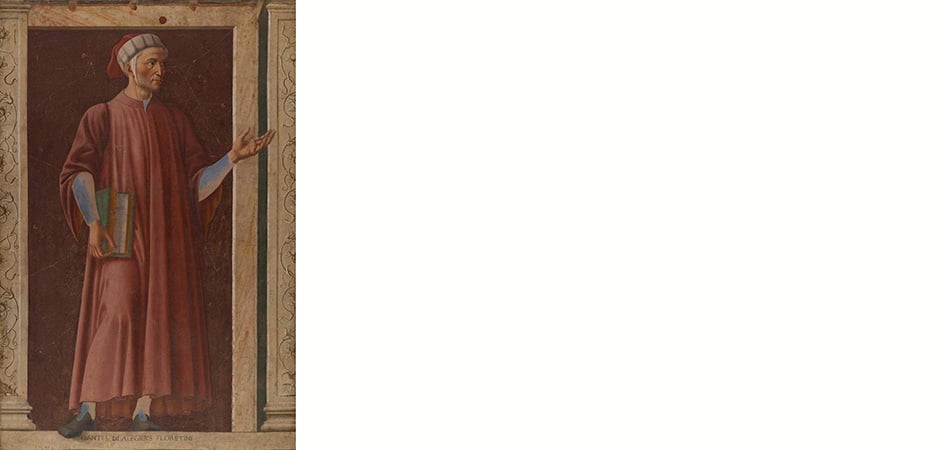

Among these is one of the oldest and most celebrated depictions of the poet: the portrait by Andrea del Castagno (1448–1449, Galleria delle Statue e delle Pitture) painted for the ancient villa Carducci-Pandolfini (near Florence). The artist portrays him in full figure, holding a half-open book and making a solemn gesture toward the figure beside him, stepping forward – with his right hand and foot – beyond the classicising frame that surrounds him.

Andrea del Castagno in fact creates a composition with a strong illusionistic character to enhance the monumentality of his figures. Alongside Dante, the fresco cycle taken from the villa also included the Florentines Boccaccio and Petrarch, three military leaders and three illustrious women. These exemplary figures were chosen to honour civic virtue and local literary excellence. Dante is identified by the inscription below and bears all the iconic traits mentioned above: the red scholar’s robe, fur-lined cap, furrowed face, a prominent nose and an expression of calm wisdom.

The Divina Commedia in painting and sculpture

Not only has Dante’s iconic appearance left a lasting mark, but his work has also given rise to a long and fruitful artistic tradition: for centuries, painters and sculptors have drawn from his Divina Commedia, allowing us today to enjoy a rich legacy of interpretations.

A prayer captured in paint

Among them, Sandro Botticelli also took on the challenge of illustrating Dante’s poem, illustrating and recalling it also in his Pala di San Barnaba (c. 1480–1482), housed in the Uffizi’s Galleria delle Statue e delle Pitture.

The panel was commissioned for the Florentine church of the same name, founded in 1289 to commemorate the Guelph victory at the Battle of Campaldino (which took place on the feast day of Saint Barnabas).

In a foreshortened and finely decorated interior, the Virgin and Child are enthroned, surrounded by angels and Saints. From left to right: Caterina d’Alessandria, Agostino, Barnaba, Giovanni (recognisable by the Saint’s typical attributes), Ignazio d’Antiochia and Michele.

But what connects this scene to Dante? A closer look reveals an inscription in the painting: on the marble base of the throne we read “Vergine madre figlia del tuo figlio” (“Virgin mother, daughter of your son”). This is a quotation from the final canto of the Divina Commedia, set in the Empyrean – the highest of the heavens and dwelling place of God in medieval theology. The words are spoken by the mystic Bernardo di Chiaravalle, who guides Dante in Beatrice’s place during the final vision of Paradiso. The poet is on the verge of being in presence of the Lord, but in order to do behold Him, the intercession of Mary is required – and it is to her that Bernardo directs the aforementioned prayer.

Dante’s tercets became so well known that they were adopted in litanies to the Virgin and, as we have seen, entered the artistic repertoire as a prayer of devotion to the Madonna.

A compendium of infernal monsters

Filippo Napoletano’s interpretation of Dante’s work is far more free and imaginative. His Dante e Virgilio all’Inferno (c. 1618–1620, Galleria delle Statue e delle Pitture) features a multitude of hellish demons drawn from various parts of the Commedia.

Against the backdrop of a gloomy, flaming architecture – possibly the City of Dis, mentioned by the poet – we glimpse Virgilio and Dante (bottom left) preparing to cross a grim and menacing landscape. The souls of the damned writhe in torment, assailed by monstrous creatures including Harpies, Hellhounds, Cerberus and Centaurs, while Charon’s boat appears on the right. Among the devils, a skeletal Death on horseback stands out – a powerful symbol of ugliness and horror. The giant lobster in the foreground, on the other hand, is an original invention by Napoletano himself: a still-life detail recalling the lavish banqueting scenes of Northern European painting, and a nod to the patron Cosimo II de’ Medici’s taste for art from beyond the Alps.

The painting’s dramatic force, vividly depicting the fate of sinners, reflects the moralising spirit of the time, shaped by the strict dictates of the Counter-Reformation Church.

A tragic and mysterious story

One of the most poignant and evocative stories for artists has been that of Pia dei Tolomei. Dante meets her in the Ante-Purgatory, where souls of the murdered who repented at the last moment await entry into Purgatory. She speaks to the poet briefly and compassionately, hinting that her death was caused by her husband, Nello d’Inghiramo de’ Pannocchieschi. The historical details of the event remain unknown, but according to the popular version, Pia was thrown from a window on the orders of Nello, who wished to marry – in a second union – a woman from the Aldobrandeschi family. This tragic tale has resonated in both art and literature.

In the 19th-century poem by Bartolomeo Sestini (later adapted into an opera by Donizetti), the jealous husband, convinced of Pia’s infidelity, imprisons her in a castle where she eventually takes her own life in despair.

Are you interested in articles like this?

Sign up for the newsletter to receive updates and insights from BeCulture!

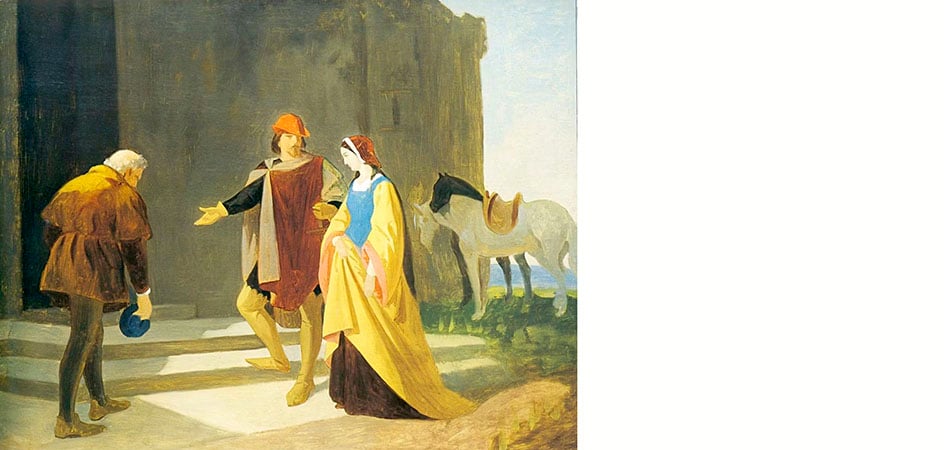

It is precisely Pia’s arrival at the castle that Vincenzo Cabianca depicts in the small oil painting held at the Galleria d’Arte Moderna in Palazzo Pitti. The painting Pia dei Tolomei condotta al Castello di Maremma (circa 1860) was executed using the block colour technique typical of the Macchiaioli movement.

Cabianca, who at the time frequented the lively Caffè Michelangelo along with a group of fellow artists, favoured a style of painting based on light and volume, abandoning academic tradition. The result is a frank and unembellished image, where essential blocks of colour depict the woman’s steady ascent of the palace steps in a clear and restrained atmosphere.

Of a very different tone and emotional “temperature” is the marble group sculpted just a year later by Pio Fedi, Nello con Pia (1861, Appartamenti Reali, Palazzo Pitti). Even the title evokes a more intimate, domestic dimension. Pia is shown welcoming her husband with tenderness and concern, though he remains distant and brooding – perhaps already consumed by suspicion and plotting her murder.

Greatly admired by Grand Duke Leopoldo II de’ Medici, the sculpture was reproduced several times by Fedi. The version we see today at the Gallerie degli Uffizi is not only one of the oldest but also the one purchased by King Vittorio Emanuele II of Italy for his personal collection at the Esposizione Italiana in 1861.

But these are only a few of the many artistic testimonies found at the Uffizi celebrating Dante’s greatness and his work – a work that is immortal, in both words.