The Devil has always assumed multiple forms in art, influenced by different traditions and cultural references, even among artists of the same era. The evolution of this essential figure (Evil opposing Good) is multifaceted and not always consistent.

In this article, we will analyze some of the prominent and easily recognizable traits of the Devil, concluding with a captivating and convincing interpretation.

The Devil as the quintessential shapeshifter

Today, we call the Devil by various names, including Satan and Lucifer. However, it’s important to remember that these names were not always interchangeable. In the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, they indicated, if not entirely different creatures, at least different aspects or moments of the same entity. For example, the Devil (or Demon) and Satan designate the Lord of Hell, commanding a host of devils tormenting souls or tempting people; while Lucifer (meaning light-bringer) is God’s favored Angel, who fell after sinning. Some critics argue that this linguistic and thus iconographic confusion is why there are no depictions of the Devil before the 9th century.

From this point on, the Devil takes on multiple forms: he is the dragon defeated by Michele in the Apocalisse (as seen in San Michele Arcangelo by Bernardo Zenale at the Galleria degli Uffizi), but also the punisher of sinners during the Giudizio Universale.

Another theme that developed between the 15th and 16th centuries is the fall of the rebel angels, peaking with San Michele che scaccia Lucifero by Lorenzo Lotto, now at the Museo Pontificio in Loreto. Iconographically, the dragon and the fallen angel have little in common, yet they represent the same entity.

The Devil’s places, or where the Devil is depicted are various: the Temptations of Jesus, the torments of Hell, the story of Teofilo, the Temptation of Giobbe, the Garden of Eden, the devils tempting and attacking Antonio Abate, and tempter devils in general.

Religious art has always served an educational and warning purpose, illustrating and reminding the faithful of sacred history and the consequences of their actions.

Thus, in many works representing the Devil, he appears as a monstrous, bestial being, but in various forms.

We must consider that even the figure of the Savior, like those of Maria and Pietro, undergoes iconographic changes over time: from the impassive and serene Christ on the cross with open eyes and separated feet of the 9th century, to the suffering Christ with feet nailed together from the 13th and 14th centuries. Beardless in the 6th century mosaics of Ravenna, Christ later takes on the features of a young man with long hair and a beard, as we are accustomed to seeing.

However, while this transformation is codified by the Church, the same does not happen for the Devil, whose appearance varies even within the same artwork. In the Libro delle ore from the early 1415 by the Limbourg brothers (Musée Condé, Chantilly), the images of Inferno e della Caduta di Lucifero e degli Angeli ribelli have nothing in common. Similarly, in the Giudizio Universale by Beato Angelico (in the Museo di San Marco in Florence), the devils are represented in many ways: with or without horns, with or without a tail, with or without wings, beings more or less dark, hairy, or hairless.

The changing characteristics of the Devil over time

Even though there is no single model for all representations of the Devil, we can identify some sources of inspiration: Pan, the satyrs and fauns of Greek mythology on one hand, and the nudity of classical art on the other. From the former, the Devil inherits an animalistic appearance. Classical nudity, however, takes on a different meaning when associated with the diabolic figure, symbolizing sin and shame instead of the exaltation of forms: the Devil has been discovered and punished. Recurring attributes include:● horns, tail, ears, hooves, and a half-human, half-animal body; ● claws or talons, likely derived from harpies or other creatures from Sasanian art; ● hirsutism; ● flaming hair, possibly of oriental origin;● a pitchfork or hooked stick, typical of jailers;● absence of genitalia;● blackness, symbolizing corruption and filth;● gaping mouth and protruding tongue;● initially feathered wings, later membranous bat-like wings from the 14th century onwards. This terrifying, grotesque being exemplifies the aberration of civilization, yet his appearance is mutable. Whether as a dragon or an angel cast out of heaven, he also takes on the face of Pan, even though Pan was not an evil god. As the Lord of the Underworld, he is often depicted as a fat, hairy, naked, black monster, perfectly described by Pope Leone I as a “black pit of filth.” In the 12th and 13th centuries, horns, hooves or claws, tail, and stick were added. He is usually depicted without wings, but when he has them, they are bat-like, and – probably in line with Dante’s description -he devours sinners while defecating.

Are you interested in articles like this?

Sign up for the newsletter to receive updates and insights from BeCulture!

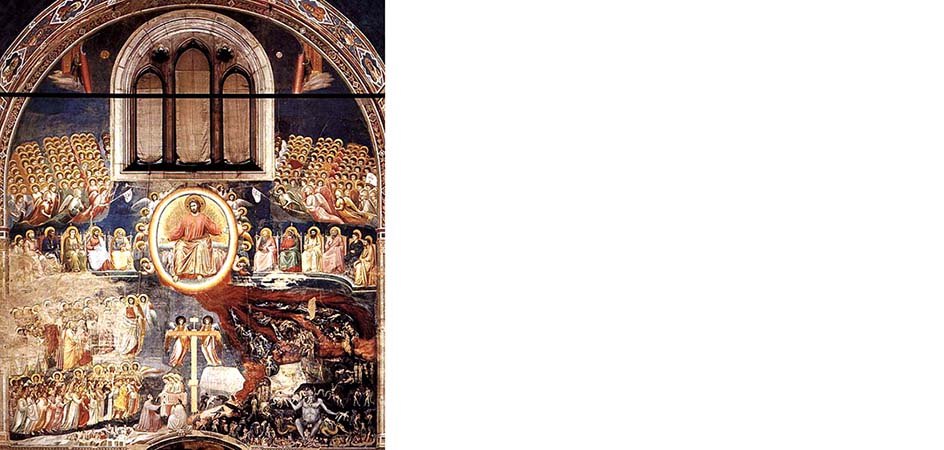

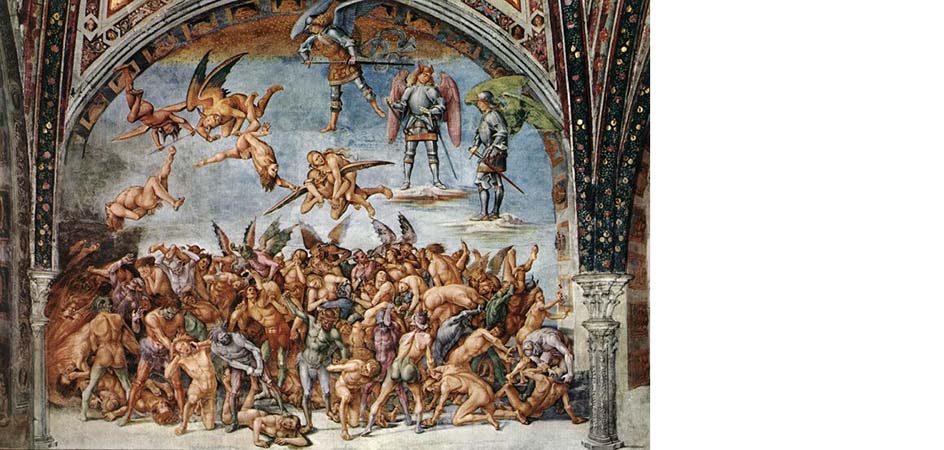

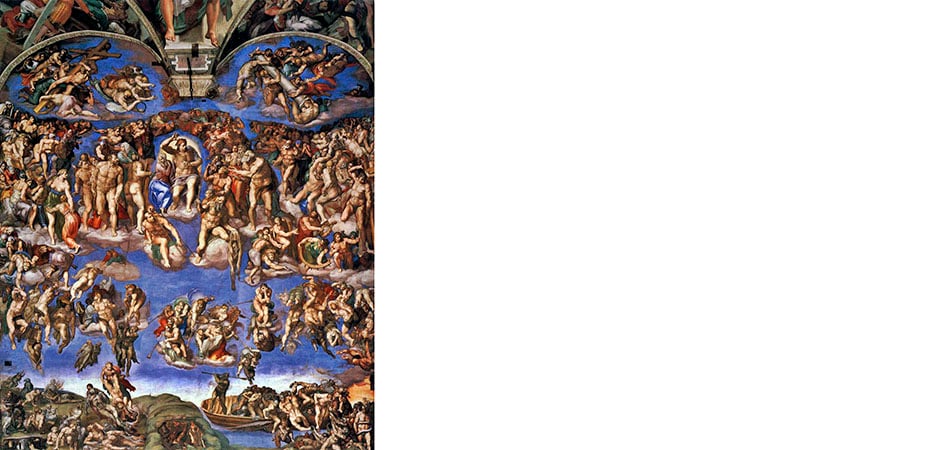

Comparing the Giudizi universali: Giotto, Signorelli and Michelangelo

To better understand the graphical and symbolic evolution of the Devil (and artistic sensibility), we can compare three representations of the same theme: Giudizio universale by Giotto in the Cappella dell’Arena (Padua, 1304-1314), Luca Signorelli’s fresco in the Cappella della Madonna of San Brizio (Orvieto, around 1503), and the famous Giudizio universale by Michelangelo in the Cappella Sistina (Rome, 1536-1541).

Giotto depicts Satan as a hairy, horned gorilla torturing the damned, eating them and smashing them around. Satan also appears in the eastern wall fresco of the same chapel, in Giuda che riceve il pagamento per il trattamento di Cristo. Here, Satan takes on a much smaller, less detailed form: a dark, poorly characterized shadow contrasting with the meticulous and psychological treatment of other characters. A dark, but marginal presence compared to the emotional impact of the scene.

With Signorelli, the Devil and his minions gain an erotic dimension, previously unknown. In the fresco I dannati, there is unprecedented violence and cruelty, with sexually charged torture, exposed nudity, and contorted bodies intertwined.

Finally, Michelangelo’s masterpiece, influenced by the Protestant Reformation and the Concilio di Trento, likely affected the subject choice, almost abandoned after 1500 and considered inappropriate even by some of Michelangelo’s contemporaries. Here, spatial distinctions between the two realms are eliminated: angels lack wings, souls are fiercely contested between Good and Evil, and Satan, as we have known him, disappears. The sense of anguish intensifies through terrified faces and torn, hollowed bodies, creating a chaotic scene where it is difficult to distinguish the saved from the damned. Satan disappears or changes form once more, appearing as Minos guiding souls to Hell.

This Minos is not just any Minos but Biagio da Cesena (according to Vasari), the Vaticano master of ceremonies who criticized Michelangelo’s bold choices.

Daniel Arasse, a French historian of Italian Renaissance art, interpreted Michelangelo’s choice as evidence of an internalization process of the Devil. From a pedagogical figure warning viewers of external dangers and temptations, the Devil becomes a vicious trait inherent in humanity. The Devil is no longer external but resides within, allowing him to take the face, even the portrait, of a real person.

In the following centuries, significant depictions of the Devil are rare. Even Caravaggio resorted to the serpent symbol in his Madonna dei Palafrenieri at the beginning of the 17th century (Galleria Borghese, Rome). Only in the late 18th and 19th centuries, during the Romantic period, do we find the Devil in the works of Goya and Blake, making this monstrous creature, now far removed from its origins, a symbol of scandal and subversion within a wholly personal imagination.

The artist’s appropriation of the Devil is complete, and the result remains astonishing.