In his essay “the gesture in art,” André Chastel warns readers about an unconscious mechanism that occurs whenever we encounter a painting with human figures. If the subject or scene depicted is familiar to us, then the gestures represented seem simple to understand; but when we do not know them, those same gestures become one of the privileged tools for deciphering the theme of the work.

In both situations, however, it is essential to remember that “the painted composition remains in any case a ‘symbolic form.’ Expressive gestures,” writes the author, “are one of the two great means available to the painter to elicit reactions comparable to those of real life”: the first is perspective, the second is the physiognomic aspect, that is, the complex of features and expressions that, combined with attitudes, characterize the figures.

Understanding the meaning of the most common gestures in Renaissance art can provide a new key to interpretation, even for works that are already well-known and seemingly obvious.

5 common gestures in Renaissance paintings

One cannot overlook, among gestures, the primacy of the hand and fingers, protagonists of gestural expression even in art. However, when trying to decipher their meaning, it is necessary to consider the context, including the body’s position, facial expression, clothing, and setting.

By analyzing recurring elements, experts have decoded the most widespread movements in the art of this period. Here we have selected five.

1. Pointing index finger

Let’s start with one of the most common and variously represented gestures: the pointing index finger. Its meaning depends on the context in which the person is portrayed but generally expresses will and authority. Michelangelo’s figure of the Creazione degli Astri in the Cappella Sistina (1508, Vatican City) fully demonstrates the power of the creative act through the gesture of the two index fingers: the right one immortalized in the act of creating the sun; the left, in the opposite direction, the moon, like an imperative and generative embrace.

If directed towards something or someone, the raised index finger draws the viewer’s attention to that object or character. But if pointed upwards, it can be a sign of challenge or – according to a motif that will become established mainly from the 16th century onwards – underline the presence of a higher power, as a warning, like in Crocifissione by Pordenone in the Duomo di Cremona (1520-1521).

We also find it as an “attribute gesture” of two figures from the Sacre Scritture: the angel of the Annunciation and Giovanni Battista. An exemplary angel is that in the Annunciazione by Benvenuto Tisi, known as the Garofalo (circa 1435), now in the Uffizi in Florence, where Archangel Gabriele points his entire arm towards Dio Padre.

As for Giovanni Battista, we cannot forget the San Giovanni Battista by Leonardo da Vinci (1513-1516, now in the Louvre, Paris). Leonardo often uses this gesture, which he considers pure, theophanic, a revelation of divine mystery (just look at the Louvre’s La Vergine delle rocce with the angel pointing towards the San Giovannino, the precursor of Christ).

2. The gesture of silence

There is another gesture linked to “the role of those extraordinary actresses that are the fingers, and in particular, the most agitated and ambitious of all, the index finger,” to use Chastel’s words again. It is the gesture of silence or signum harpocraticum from Harpocrates, the god of silence in Greek and Roman mythology, depicted with a clenched hand and raised index finger covering the lips.

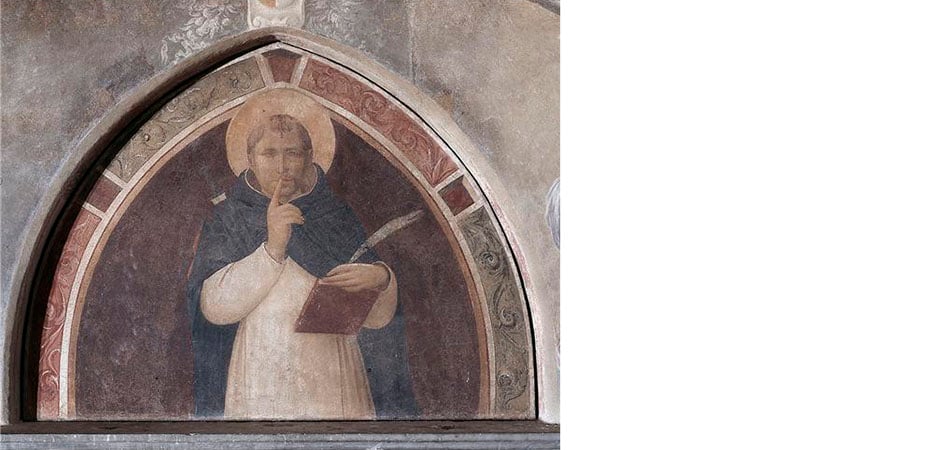

This sign also appears in the Renaissance, associated here with saints and monks depicted in convents, refectories, dormitories, and even in passageways, such as lunettes and arches. Control of speech, to facilitate meditation and listening to the inner voice, but also control of the body and its impulses: all this is encompassed in the gesture of silence.

It is well visible in San Pietro Martire by Beato Angelico (circa 1442, Florence, San Marco convent). Located in the lunette of the door leading from the cloister to the church, the saint almost seems to lean out to enjoin silence: an additional warning anticipating the sacredness of the place.

3. Speaking hand

A painting can invite silence, but it can also express the action of speaking.

The open hand had this very role: since classical times, orators were identifiable by the position of the arm extended forward, with the index and middle fingers extended or the entire palm open. A scheme adopted by Christians to signify the word of God: the gesture of blessing is indeed very similar to that of speech.

In the Renaissance, the entire body is added to the hand, but its function and iconography remain unchanged. A veritable concert of voices can be read, for example, in the late 15th century miniature by Giovanni Pietro da Borgo (Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe in the Uffizi) depicting Francesco Sforza in conversation with his captains. A completely static scene, animated only by raised indexes and hands calling to each other.

But it is possible to recognize a similar gesture in numerous annunciated Madonne, first among them Botticelli‘s circa 1489-1490, housed in the same museum: here, the angel announces God’s will, while Maria receives it with palms facing outward.

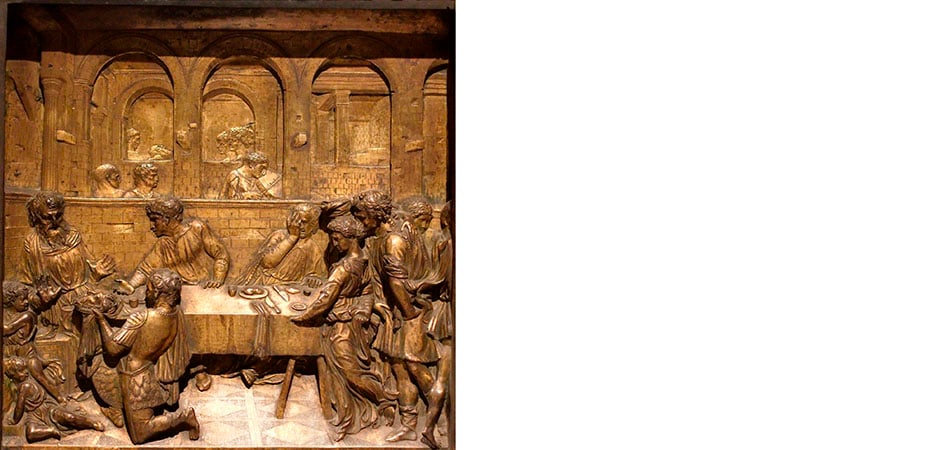

A mimicry resembling that of the speaking hand but which can assume different connotations depending on the context: of welcome and availability, as in this case, or of repulsion and rejection, as in Donatello‘s bronze Erode for the baptismal font of Siena (Il banchetto di Erode, 1425-1427, Siena, Battistero). Before the head of the beheaded San Giovanni, Erode recoils in horror and raises both hands in the speaking gesture, as if to declare his horror (and error).

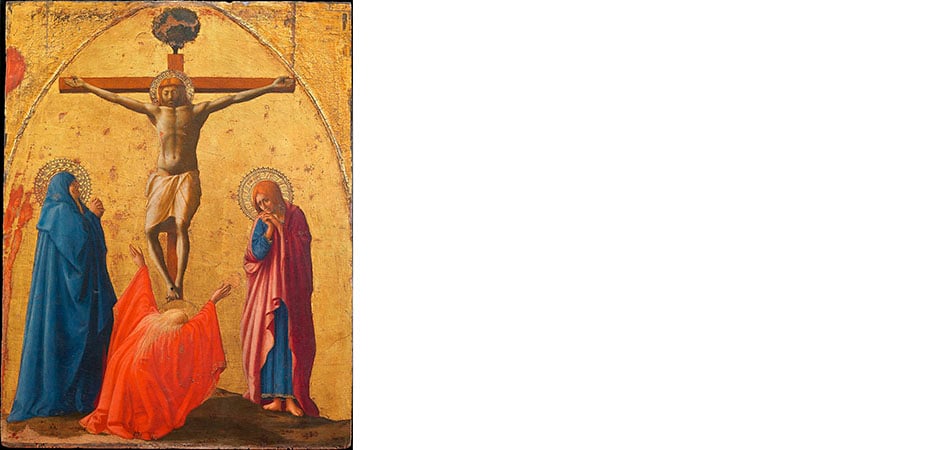

4. Gestures of despair: outstretched arms and hands covering the face

Despair remains mute in paintings, but it is no less explicit for that. Outstretched arms raised towards the sky are the most evident expression of it, and the extent of the gesture expresses different degrees of affliction. Among the most vehement is Maria Maddalena at the foot of the cross in Crocifissione by Masaccio del Polittico di Pisa (circa 1426, Naples, Museo di Capodimonte), with her body dramatically projected forward and arms stretched in the air.

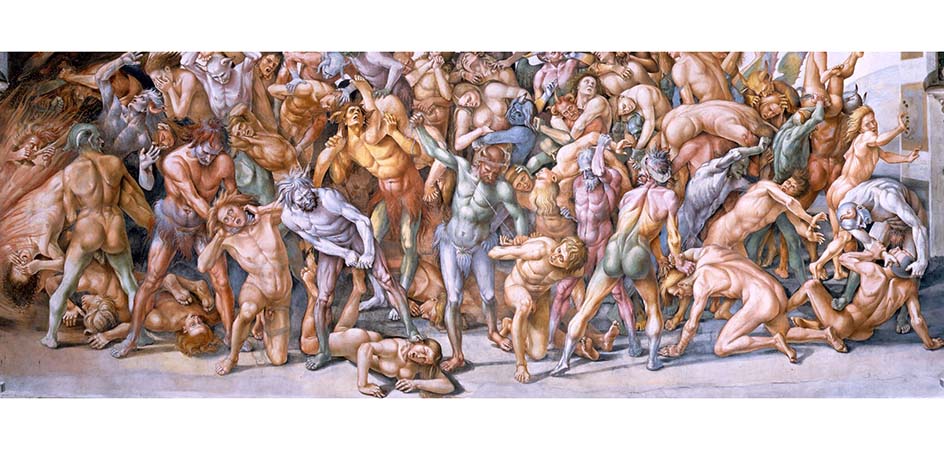

In depicting the demons tormenting the damned in his Giudizio Universale (1499-1502, Duomo di Orvieto), Luca Signorelli uses a similar pose to represent pain and anguish.

To this is added a less theatrical but equally effective and pathos-laden pose: hands covering the face. It is found in Signorelli, as in Masaccio (this time in the figure of Adamo, distraught, in the Cacciata dal Paradiso Terrestre of 1424-1427 in the chiesa di Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence). And again – making a leap forward a few centuries – in Morte della Vergine by Caravaggio of 1606 (Paris, Louvre), where the gesture reaches an unprecedented emotional naturalism, also because performed by multiple subjects.

Are you interested in articles like this?

Sign up for the newsletter to receive updates and insights from BeCulture!

5. Joined hands

The gesture of prayer, with hands joined and fingers extended at chest level, may seem banal today, but its history is very interesting. Until the entire High Middle Ages, prayer was expressed with open arms (the gesture of the orant).

Joined hands, however, were a sign of submission, typical of prisoners or vassals who, during the homage ceremony, placed them between those of their lord as an act of subjection.

The francescani were among the first to modify the execution of prayer and, consequently, its iconography when, during liturgical functions, they began to raise the host between the two hands, to express reverence and ask for grace. From here, the diffusion of a gesture that encompasses all these intents and to which is added, over time, that of supplication and imploration.

The gesture is found in many compositions on sacred themes. One above all, La Madonna della seggiola by Raffaello (1512, Palazzo Pitti), where a small San Giovannino contemplates Mother and Child, joining his hands in a tender prayer.

These examples demonstrate the symbolic power of gestures and their meanings, which in many cases have endured to this day.

On the other hand, non-verbal communication is still part of our culture, and our country is famous worldwide for its pronounced mimicry. A characteristic that could not escape a curious and attentive mind like that of Bruno Munari, designer and artist, who dedicated an illuminating Supplemento al dizionario italiano (Supplement to the Italian dictionary) on the subject: a highly recommended read to decipher the body language of today’s Italians and, who knows, maybe even some typical Renaissance gestures…

Supplemento al dizionario italiano, Bruno Munari

A little spoiler: the “marameo,” with the thumb on the tip of the nose and the other fingers stretched in succession, was already done then, but we’ll let you discover its meaning!