If, while strolling through the narrow streets of Florence’s historic center, you’ve ever wondered what it was like to live during the time of the guelfi and ghibellini or the Renaissance, then you must not miss a visit to Palazzo Davanzati on the ancient Via di Porta Rossa. This authentic 14th century residence, which has remained almost intact, still preserves traces of the families that inhabited it over the centuries and houses an exceptional Museo d’arte e artigianato. Let’s discover it together.

The palace and its history

An aristocratic residence, a hub of shops, an exhibition venue, and finally a Museo nazionale – Palazzo Davanzati has a long and intriguing history that begins in the 14th century when the Davizzi family, Florentine merchants and bankers, built it.

The building remained in their possession until 1516, the year it was sold to the prelate Onofrio di Lionardo di Zanobi Bartolini. The Bartolini, who had grown wealthy through the Arte del Cambio, had acquired several properties in the city. However, their fortune was destined to wane in a short time: in 1578, facing financial difficulties, they sold the palace to Bernardo Davanzati, a renowned Florentine historian and scholar, from whom it took the name it still bears today.

The distinguished family retained ownership until 1838 when the last heir, Carlo di Giuseppe Davanzati, committed suicide by throwing himself from a window of the palace.

From private home to commercial showcase

Divided among various owners, the building was purchased in 1904 by the antiquarian Elia Volpi, who, after restoring it over five long years – largely reinstating its original features – furnished it with his collection of medieval and Renaissance furniture and artifacts. It was during these years that Palazzo Davanzati became internationally known as the Museo della Casa Fiorentina Antica, offering the enterprising Volpi the opportunity to tap into the American market. In November 1916, all his furnishings were taken to New York and auctioned off. The result, thanks to savvy promotion orchestrated by Volpi himself, was astonishing: a total sale of $1 million with very few items remaining unsold.

Everyone in America wanted a piece of the Florentine house, so much so that many openly drew inspiration from it to furnish homes, offices, hotels, and even ships.

Towards the birth of the Museum

In the early 1920s, Volpi decided to retire from commerce and, in 1926, sold his precious showroom to the Benguayat brothers, antiquarians from Alexandria, Egypt, with shops in Paris, London, and New York. They immediately undertook renovation work, especially on the inner courtyard and cellars, attracting the antipathy and criticism of the Florentines who, from various quarters, demanded its preservation. Deep in debt and intent on offloading the palace, the Benguayat put it up for auction in 1934, without success.It was only in 1951 that it was purchased by the Italian State and opened to the public the same year with a new exhibition of objects from the collections of the Florentine Galleries, later enriched by donations and subsequent purchases, which are still on display today.

Are you interested in articles like this?

Sign up for the newsletter to receive updates and insights from BeCulture!

Features and peculiarities of Palazzo Davanzati

Its history is one of the elements that add to the fascination of this incredible palace, which still retains on its façade many features from the 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries.

The building develops vertically over four floors, in line with the needs of the Middle Ages when urban space, circumscribed by protective walls, was limited. The ground floor features three large openings with lowered arches – a common motif in Gothic Florentine houses – framed by rusticated stonework and surmounted by three small windows.

On either side of the portals, the rings for tying up horses are still present, while next to the windows of the upper levels, you can spot the iron brackets that once held torches to illuminate the palace.

Along the façade, you can also notice curious wooden poles. But what were they used for?

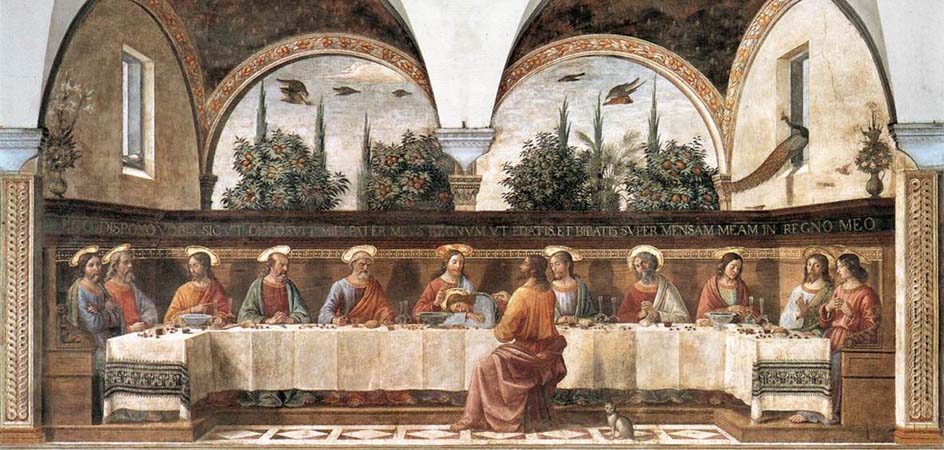

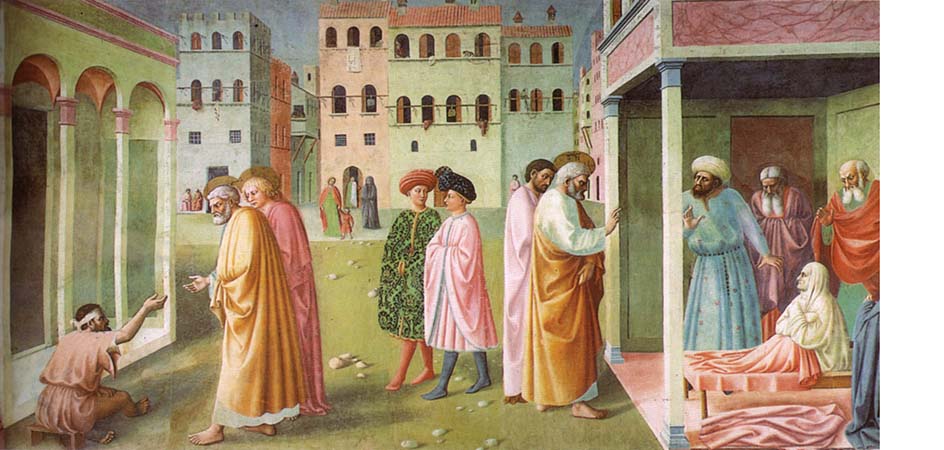

It’s probable they were used to hang laundry, or to suspend shading curtains and decorative drapes for festivities, or even to tie cages of birds, dogs, or macaques left to get some air on the windowsills – a very unusual custom for us today, but evidenced by frescoes such as the Resurrezione di Tabita (circa 1424-25) by Masolino and Masaccio in the church of Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence.

Dominating the façade, above the central window of the first floor, is the coat of arms of the Davanzati family dating back to the 16th century. From the same period is also the terrace with a loggia that crowns the palace.

The interiors and their decorations: from the halls to the nuptial chamber

Let’s enter and walk through the spacious ground floor, occupied by a large hall.

Until 1498, when it was divided to host some shops of the Arte della Lana, this was the gathering room of the Davizzi family, opening directly onto the street. It was here that they met to conduct their public and private affairs, celebrate festivities and weddings, and hold funeral rites. Various frescoes with the family’s coats of arms are still visible on the walls.

Beyond the hall, the inner courtyard – a true exception for houses of that era – gives access to the staircase leading to the upper floors. Before ascending, we invite you to observe the columns of the loggia: you’ll notice that one is different from all the others. Its capital, dating to around the mid-14th century, does not feature vegetal motifs but male and female heads, which some critics have interpreted as portraits of the Davizzi family.

Among the typical elements of ancient houses, we also recognize the small lion or “marzocco” carved and placed at the beginning of the balustrade (one of the most famous is by Donatello, now preserved in the Museo del Bargello). As we ascend to the first floor, we’re greeted by a 15th century image of San Cristoforo, then widely displayed for its supposed protective function.

Here are also two of the most famous rooms of the palace: the Sala dei Pappagalli and the Sala dei Pavoni, which owe their names to the exotic birds finely depicted on the walls.

The Sala dei Pappagalli, in particular, is distinguished by faux tapestry that simulates the presence of a curtain, even imitating its folds around the fireplace and corners.

But the real gem is hidden inside the Camera Nuziale on the second floor, whose walls are frescoed with episodes from a French chivalric poem.

Composed in the 13th century, La castellana di Vergi tells the story of the unfortunate love between the knight Guglielmo, a valiant servant of Duke Guarnieri di Borgogna, and the lady of Vergi, the Duke’s cousin. Secret lovers, they are forced to reveal themselves when the Duchess di Borgogna, infatuated with Guglielmo, tries to seduce him and – rejected – accuses him of assault. Questioned by the Duke about the incident, Guglielmo declares his innocence and defends himself by admitting his relationship with another woman. The Duke then gives him a terrible ultimatum: reveal the name of his beloved or go into exile. After ten days of reflection, the knight decides to reveal the woman’s identity to the Duke. The Duchess, furious with jealousy, invites her to court and ridicules her in front of all the other ladies. Unable to bear the shame, the lady kills herself, and Guglielmo does the same after finding her dead. By carefully observing the frescoes in the room, you can recognize the key moments of this tragic story, which seems to foreshadow the sad fate of another couple. It’s probable that the decoration was made in 1395 on the occasion of the wedding between Francesco di Tommaso Davizzi and Catalana degli Alberti. However, the marriage would last little, as only five years later, Francesco was tortured and sentenced to beheading for political conspiracy.

Comforts and peculiarities of this ancient noble Florentine house

Not only beauty but also comfort: Palazzo Davanzati stands out for the rare amenities it was equipped with, unusual even for the wealthy class of its first owners.

While visiting the rooms, you might notice some small openings in the walls protected by shutters. These are internal windows that open onto the shaft of the private well, which served all the rooms thanks to a system of pulleys – a real luxury in an era when wells were almost all public.

The heating needs and kitchen requirements were usually met by open hearths (without masonry structures), but here we also find numerous stone fireplaces, further proof of the prosperity of its inhabitants.

Finally, one last detail catches our attention: the numerous “guardarobe” or “agiamenti” or “privati”, as bathrooms were called then. Designed to discharge waste into an underground cistern (which then emptied into the alley behind the palace), they are present in several rooms. Some are even decorated with floral paintings or faux ermine curtains; the one in the nuptial chamber is even double, with two communicating spaces.

What to see at the Museo Davanzati: 3 works to focus on

Furniture, everyday utensils, ancient artifacts – the Museo Davanzati, which unfolds through the rooms of the palace, houses a marvelous collection of objects of great historical and artistic value, following the program of Luciano Berti, the first director.

Among these, the following stand out:

- the Trionfi by Guidi Giovanni Di Ser Giovanni known as Lo Scheggia (circa 1440-1460), younger brother of Masaccio and also the author of the so-called Cassone Adimari, now at the Galleria dell’Accademia in Florence. In the four curved panels, inspired by Petrarca’s poem of the same name, we recognize the Trionfo dell’Amore, della Morte, dell’Eternità, della Fama. It has not yet been possible to understand their exact use with certainty: it’s hypothesized that they were part of the base of a central piece of furniture or a sculptural group, or that they were intended for wall paneling. The new placement, in the Camera delle Impannate, enhances their beauty and allows visitors to admire them in all their uniqueness;

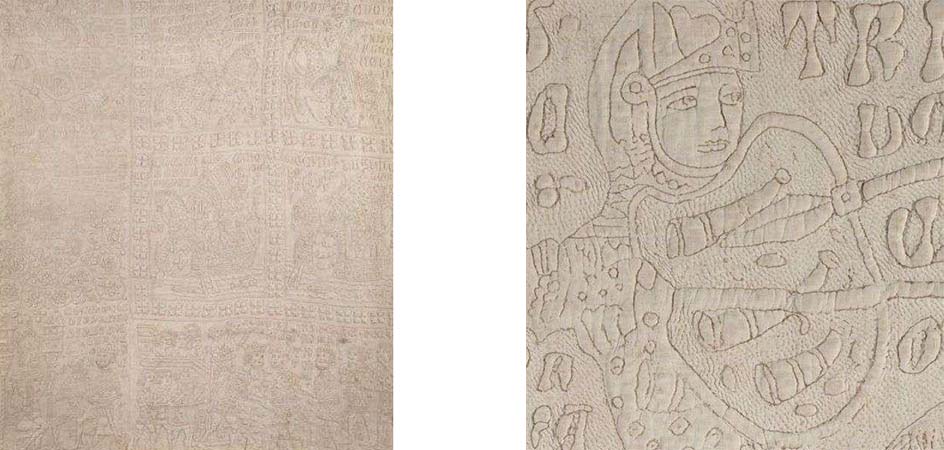

- the Coperta Guicciardini or of “Usella”, an extraordinary piece of Sicilian “trapunto” from the late 14th century. A technique introduced in Italy already at the end of the 13th century and in Florence in the 16th century thanks to the dissemination efforts of Caterina de’ Medici, as revealed by some details typical of French boutis. The Coperta Guicciardini depicts part of the medieval epic poem Tristano e Isotta and was found by the wife of Count Guicciardini in their villa of Usella, near Prato, in 1890;

- the rare painted wardrobe from 1500 of Sienese origin, already part of Elia Volpi’s collection. The inscription in silver capital letters on the architrave indicates its function, later further refined by the subsequent insertion of a gun rack and a drawer for gunpowder. On the original doors, the elegant grotesque motifs that made it famous have been preserved.

Before leaving the building, don’t forget to go up to the third floor, where the museum’s precious collection of lace and embroidery has recently been rearranged. It’s a selection of the most important pieces, organized by geographic area, manufacture, and chronology, which will lead you to discover this ancient art and its developments from the 17th century onwards.

With its characteristic architecture, decorated rooms, and antique furnishings, Palazzo Davanzati takes us back in time and immerses us in the daily life and habits of a wealthy Florentine family – an experience that deserves to be lived!