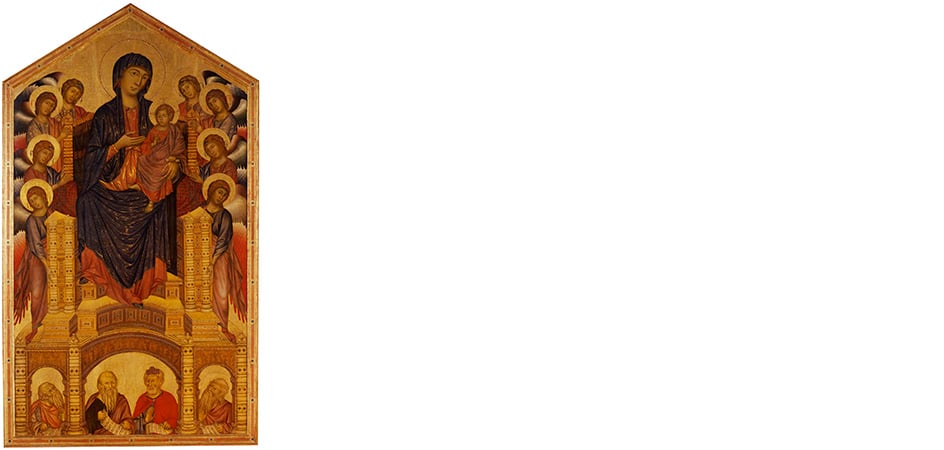

Entering the Sala delle Maestà at the Uffizi in Florence, one cannot help but be struck by the imposing works that occupy the walls. The essential arrangement allows one to fully appreciate, without distractions, the three panels by Duccio da Buoninsegna (Madonna Rucellai, 1285), Cimabue (Maestà di Santa Trinita, 1290-1300), and Giotto (Maestà di Ognissanti, 1305-1310).

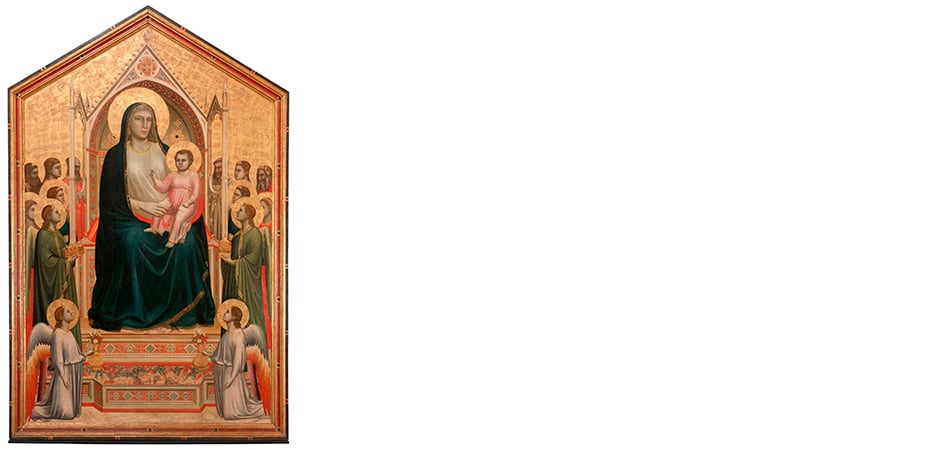

It is the latter, prominently displayed on the central wall, that first welcomes the visitor and stands out significantly – even to less expert eyes – from the other two.

We focus here on the Maestà by Giotto to understand its origin, meaning, and exhibition history.

Origin and iconography

The Maestà di Ognissanti is named after its subject and original location. The term Maestà refers to depictions of the Virgin and Child enthroned and surrounded by angels, a common motif in central Italy during the 13th and 14th centuries.

Ognissanti is the name of the Florentine church from which this panel originates.

We do not know with certainty who commissioned the work from Giotto, but it is likely that it was the Umiliati order, a wealthy company of friars who inhabited and administered the church. The date of execution is also uncertain, commonly set between 1305 and 1310, when Giotto was already a renowned artist called to work throughout the peninsula, appreciated for the new naturalism he had introduced in his works.

An attentive observer of natural phenomena, Giotto brought about a change as evident as it was fundamental for the development of future Renaissance painting, clearly visible in his Maestà.

The Madonna by Giotto sits on a richly decorated throne with the Child in her lap, captured in the act of blessing the onlookers with his right hand while holding a scroll in his left. Hosts of Angels and Blessed gather around the structure bearing gifts, while at her feet kneel two cherubim offering flower vases.

Unlike the panels by Duccio and Cimabue (both characterized by the rigidity of their composition and formal elements typical of Byzantine art, such as the golden decorations of the garments), Giotto’s figures present a new corporeality through the draperies that softly outline the forms. For the first time, faces express feelings and intentions: solemnity, reverence, but also sweetness, like the barely hinted smile of Maria, the first in the history of art. Then there is the space, meticulously described in the materials and details of the throne, to which Giotto gives a depth that is not yet perspectival but no less suggestive: the arrangement of the Blessed in multiple rows, with their heads overlapping, gives the optical illusion of a three-dimensional environment. Beyond the visible faces, one can also see signs of other halos, an expedient that increases the perception of a continuous multitude.

If Giotto, in the words of Cennino Cennini, “was the one who changed the art of painting from Greek to Latin,” this Maestà is undoubtedly one of the most successful demonstrations. However, what may seem to contemporary eyes a simple composition to decipher actually retains many hidden symbols and meanings.

Characters and symbols in the Maestà by Giotto

Among scholars who have questioned the identity of the figures surrounding the Virgin and Child in this Maestà, Margrit Lisner has provided one of the most convincing and accredited interpretations. According to the author, the ideal division of the painting into two halves, with Maria on the left and the Child on the right, can help decipher the other figures.

Looking at the panel and starting from the bottom, the kneeling angels, one notices the flowers: white and red roses and lily branches, symbols of Maria’s virginity, chastity, and charity. These same flowers are referred to in the scroll with the Virgin’s words in Simone Martini‘s Maestà fresco at the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena (1313-1321): “The angelic flowers, roses, and lilies, / with which the heavenly meadow is adorned…”.

The two angels in green tunics standing on the first step, to the left and right of the divine group, offer respectively a crown, a reference to Maria as Regina dei Cieli, and a covered Eucharistic ciborium (a sacred vessel that contains the hosts), alluding to Christ’s Passion.

In the two women dressed in red and partially covered by halos just above, it is possible to recognize the martyr saints Lucia (on the left, with a veiled face) and Caterina of Alexandria (on the right, with a crown). The former was particularly dear to the Umiliati, and the veil suits her chastity and that of Maria, while the latter was always devoted to God and recalls his Passion.

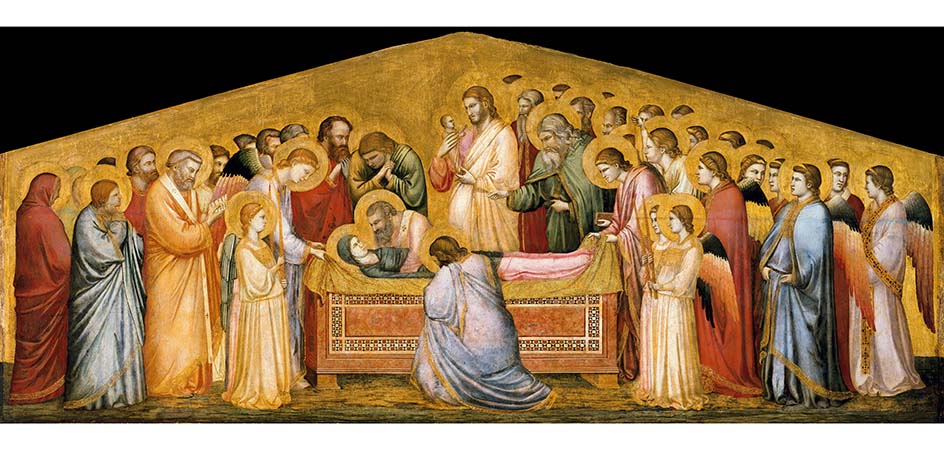

Furthermore, the two bearded monks standing out behind the wide tracery of the throne, in the last row, can be identified as San Paolo, bald and dressed in red (as already in the Morte della Vergine by Giotto, 1312-1314, also for the church of Ognissanti, now in Berlin), and San Benedetto, with a white robe like that worn by the Umiliati. San Paolo is indeed the greatest witness of the Assunzione di Maria – hence he is on her side – while Benedetto is again linked to Christ’s Passion.

Behind Paolo, there would instead be a young San Giovanni, who contrasts, on the opposite side, with a young Isacco. There is some uncertainty regarding the reading of the last figures, and they could be the Patriarchi (Abramo, Isacco, and Giacobbe) or Profeti (Geremia, Daniele, and Isaia).

Finally, not least important, the novelty of Maria’s robe: not red or blue, as per tradition, but white. A color that Giotto also uses a few years earlier in the fresco cycle of the Cappella degli Scrovegni when representing young Maria. While white can be explained as a symbol of purity, the meaning of the Virgin’s mantle lining, unusually red, is less clear, likely referring to the Passion of her Son (note that the fabric passes between the Child’s legs, dressed in pale pink).

All these figures contribute to the unified sense of the work: that of Salvation.

Maria evokes forgiveness and mercy, while the blessing Christ and the various references to the Passion speak of redemption. Examples of God’s Grace are the Martyr Saints and San Benedetto, along with the host of Blessed and Angels gazing at the Savior in an act of adoration.

The uncertain placement

In addition to identifying the characters, the question of the exact placement of the panel within the chiesa di Ognissanti remains open, today much different from how it was in the 14th century.

Critics now agree in refuting the thesis that it was placed on the main altar, where it would have been replaced from 1360 by Giovanni da Milano’s polyptych (unfortunately now dismembered into several parts, some of which are kept in the Uffizi). The reasons are as follows: first, it is unlikely that a Lombard artist would have supplanted the work of a local artist of Giotto’s stature, who, so shortly after his death, enjoyed even growing fame.

Approaching the Giotto painting, one notices some details that seem to indicate a lateral arrangement – and thus a lateral point of view – rather than a central one along the church’s axis. First, consider the light: beyond the illumination radiating from above (interpretable as divine light), another light source should ideally be placed high on the right, outside the frame. This is evidenced, for example, by the shadowed right interior of the throne (whereas the left side appears illuminated); the Virgin’s mantle lightened at the knees and folds toward the right and darker on the left side; the sharp contrasts between light and shadow on the figures placed on the left, as if struck by a glow from the opposite direction.

Additionally, the overall asymmetry should be highlighted, starting from the steps’ perspective, with the left side less steep than the right, and the throne’s flanks, one more “open” than the other. The decorated interior of the edifice also appears narrower on the left than on the right.

Maria and the Child also participate in this apparent disharmony: the Child seems to bless those standing to his side rather than in front, and Maria’s strabismus, which corrects or disappears entirely when viewed from the left, has been noted.

According to experts, this was the privileged viewpoint, to which Giotto consciously leads through these visual devices that lose effectiveness when viewed frontally.

So, where was the Maestà originally placed? We do not have certain information, but it is likely it was on a side altar or on the rood screen separating the laity’s space from the Umiliati choir.

Are you interested in articles like this?

Sign up for the newsletter to receive updates and insights from BeCulture!

What is certain is that it enjoyed mixed fortunes. Despite numerous praises over time, by the end of the 18th century, the memory of this panel and its author had perhaps been lost, to the point that it was attributed to Cimabue.

In September 1810, with the French imperial decree of Saint Cloud (which established the suppression of convents also in Italy and the removal of their works), the panel was removed from the church and taken to the Galleria dell’Accademia. From there, it arrived at the Uffizi at the beginning of the 20th century, severely compromised, marked by deep cracks and 19th-20th century paint alterations.

The subsequent restoration, masterfully conducted by Alfio Del Serra, restored its beauty and integrity, revealing even hidden details like the decoration imitating the kufic script on the frame.

The Maestà di Ognissanti is not only a rare work but truly unique, demonstrating the compositional achievements reached by Giotto in the early 14th century. It is therefore not surprising that some scholars already consider him a Renaissance painter.

Beyond critical readings, the panel certainly deserves the prominent place given to it by the Florentine museum, which we invite you to visit as soon as possible.