If Florence is the capital of the Renaissance, Rome is certainly the homeland of Italian Baroque: it is here that, starting from 1630, some of the most successful works of this incredible era were created. An era marked by the search for a new artistic language capable of responding to the communicative needs of the Catholic Church, intent on reaffirming its influence over the faithful after the Lutheran Reformation.

In this dense cultural landscape, two figures stand out for their skill and fame: Gian Lorenzo Bernini and Francesco Borromini. Divided by a bitter and irreconcilable rivalry, they are the main protagonists of 17th century architectural innovation and shaped much of Baroque Rome during this period. In this five-step walk, we explore some of their most representative buildings, witnesses to their lively antagonism.

1. San Pietro: from Baldacchino to the Piazza

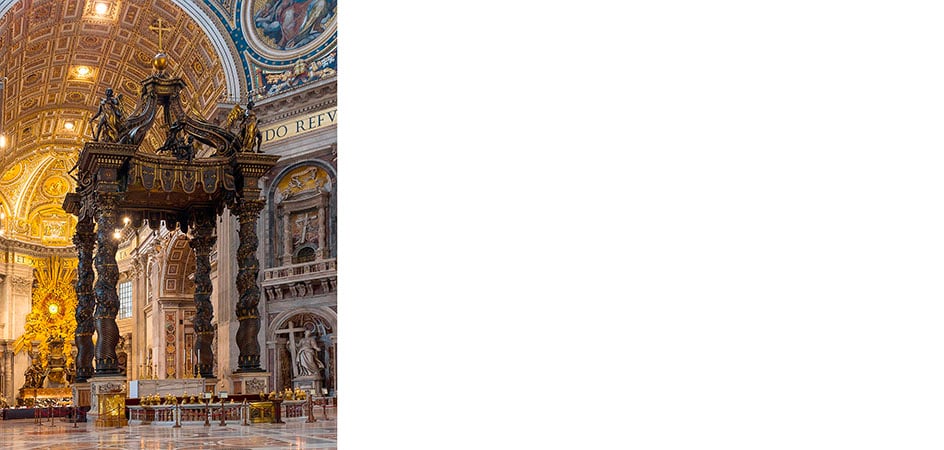

Straddling architecture and sculpture, the Baldacchino of San Pietro (1624-1635) marks the beginning of our journey, as well as the start of the collaboration – and subsequent separation – between Bernini and Borromini.

Upon the death of Carlo Maderno, the project leader for whom both were already working, Bernini received the commission for the bronze Baldacchino directly from Pope Urbano VIII (Maffeo Barberini).

To create it, Gian Lorenzo drew inspiration from numerous previous projects, synthesizing and surpassing them at the same time. Among the most surprising innovations are the four twisted columns: already present in Martino Ferrabosco’s proposal (a sculptor and restorer responsible for several interior and exterior projects of the Basilica), they are slimmed down and raised to reach 20 meters. Despite their monumental size, they are slender and free on all sides so as not to obstruct viewers’ gaze toward Michelangelo‘s cupola. The perception of various spatial elements depending on the point of view is indeed one of Bernini’s major concerns; he always studied his works in relation to people’s movement in the environment, creating ingenious overlaps of solids and voids.But the real problem arose during the crowning phase. Initially, Bernini had imagined a structure composed of two semicircular arches crossing diagonally and supported at the base by four angels. However, this layout appeared, even in the drawing, too rigid compared to the movement of the columns. At this point, the young architect turned to his colleague Borromini, more experienced than him on a technical level. The dolphin-back volutes we see today – key elements in giving dynamism to the ciborium – are the happy result of their collaboration destined, unfortunately, to end in conflict. After completing the project, Borromini not only did not receive adequate pay (a tenth of Bernini’s!), but also did not obtain the promised recognition for his work. An affront too great to bear, causing an irreparable rupture in their relationship.

Favored by the pope, Bernini – who had been appointed director of the Fabbrica di San Pietro – carried out many other interventions in the Basilica, although not all were successful.

Among these was the construction of the torri campanarie, already planned in Maderno’s project and later modified. The first, completed in 1641, was demolished shortly after by the new pontiff Innocenzo X because it was considered unsafe – a judgment expressed by many, including, unsurprisingly, Francesco Borromini. This caused a temporary setback in Bernini’s career. Nothing too serious, however, so much so that a few years later we find him engaged in the arrangement of Piazza San Pietro (1656-1667), with its famous trapezoidal layout enclosed by semicircular colonnades. Two hundred eighty-four columns arranged in four rows, above which stand 140 statues of saints – a decorative motif that elegantly varies the regular rhythm of the colonnade. It is undoubtedly one of the most renowned squares in the world.

2. The perspective of Palazzo Spada

Meanwhile, Borromini – having distanced himself from San Pietro’s project and embarked on an independent path, bolstered by a certain economic independence – sought to make himself known and forge new relationships. On one hand, he offered to work for free on the restoration of the Chiesa di Santa Maria di Loreto and the construction of the Chiesa di San Carlino; on the other, he came into contact with the Spada family.

Commissioned to renovate their residence (formerly Palazzo Capodiferro), he created his famous Colonnata here. This is the second stop of our tour, reachable on foot via the Ponte Vittorio Emanuele II, from which one can also enjoy the view of Castel Sant’Angelo and the eponymous bridge adorned with Bernini’s statues.

Located in the garden of the Galleria Spada, the Colonnata is one of the greatest examples of Borromini’s architectural ingenuity and the spirit of Baroque in Rome. A gallery built with a clever illusionistic play that deceives the viewer through a rigorous perspective construction: what appears to be a corridor of at least 30 meters actually shrinks to only 9 meters.An optical effect that is not an end in itself: besides giving the idea of infinite space – a concept dear to the 17th century – the Colonnata serves as a warning against the dangers of worldly life, which is not always as it appears.

3. Sant’Ivo alla Sapienza

Ascending from Galleria Spada towards Campo de’ Fiori, a few steps from the Pantheon, stands the Chiesa di Sant’Ivo alla Sapienza, located within the eponymous Palazzo, the seat of the ancient Università Romana and today the Archivio di Stato. The chapel, commissioned to Borromini by Urbano VIII in 1632, is proof of his brilliant inventiveness. Despite being constrained by pre-existing structures, it represents a true jewel of 17th century architecture.

Borromini developed the building on a complex plan with a strong symbolic charge: a sort of six-pointed star composed of two interlocking equilateral triangles. The triangle, emblematic of the Trinità, also recalls the bee, which in turn symbolizes Charity and Prudence and is a heraldic element of the Barberini family coat of arms. But even more astonishing are the solutions adopted for the roof.

The polylobed dome features interior niches and fluted pilasters that emphasize its height, while the monochromatic white decoration amplifies the luminosity of the space. Bold and sensational is the lantern that surmounts it: its spiral shape – twisted and sinuous – reaches toward infinity and almost seems to challenge the vertiginous heights of Gothic architecture. Crowned by a flaming crown on which rests a sphere, a cross, and a dove with an olive branch in its beak, all in wrought iron, it rises toward the sky seemingly weightless.

4. Sant’Andrea al Quirinale

Let’s leave Sant’Ivo alla Sapienza behind and move now toward Sant’Andrea al Quirinale, once again following Bernini’s trail.

Observing the exterior of the church, one immediately notices the refined interplay of contrasts between rigidity and movement, curved lines and straight lines, which intensifies and manifests itself more strongly inside. Smooth pilasters that interrupt the curvilinear motif of the porch frame the façade, consisting of a single architectural order.

Inside, the elliptical plan is highlighted by the magnificent dome with a lantern. The vertical ribs that converge toward the central oculus, the hexagonal coffered decoration, and the stucco figures that animate the base give the environment a unique grandeur.

The light that enters through the numerous side openings creates luminous effects that change the perception of the space at different times of the day.An effect that Bernini had anticipated and sought: this, according to the architect and sculptor, was indeed his best work, the perfect synthesis of all the arts.

Sei interessato ad articoli come questo?

Iscriviti alla newsletter per ricevere aggiornamenti e approfondimenti di BeCulture!

5. Piazza Navona

Let us now retrace our steps to head toward Piazza Navona, where our itinerary concludes. Here we find, once again as rivals, Bernini and Borromini.

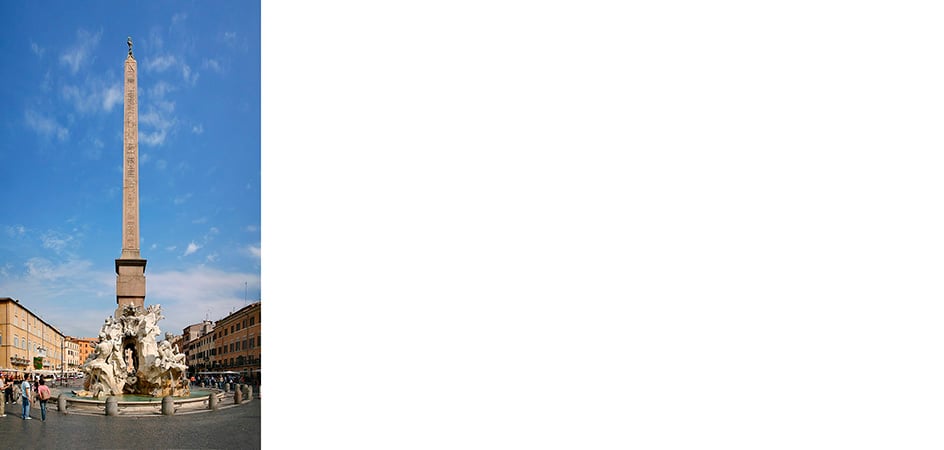

The imposing Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi, a work of architecture as well as sculpture – commissioned by Pope Innocenzo X and completed in 1651 – is the last testament to the discord between the two. It seems that Bernini managed to snatch the commission from Borromini, to whom we owe, moreover, the idea of representing the Quattro Fiumi.

It is certain that the result amazed both the patron and the public, also due to the truly surprising idea of the obelisk resting on an empty space. In the figures of the Nile, the Ganges, the Danube, and the Río de la Plata, we can still admire today one of the highest achievements of Bernini the sculptor, as well as – according to popular belief – one of his last affronts to his detested colleague.

Borromini, on the other hand, was asked to take care of the restoration of the facing Chiesa di Sant’Agnese in Agone, which the architect reimagines especially in its external composition. The convexity of the façade, which echoes the curvature already experimented with a few years earlier in the Oratorio dei Filippini, represents the allegory of an embrace that metaphorically welcomes bystanders, creating continuity with the surrounding buildings.

Legend has it that the Nile and the Río de la Plata – the two river figures facing the church – are intent on covering and shielding their faces from the ugliness of Borromini’s work.

An affront more invented than real, but one that effectively conveys the idea of the tension between the two. Perhaps only here, in this marvelous square, can they finally find reconciliation, united by their shared contribution to the Baroque splendor of Rome.