Italian design, celebrated for its influence on the culture of home furnishings and industrial products, has etched a place of pride in our modern history.

It’s globally recognized and revered, thanks to a serendipitous fusion of visionary creativity and savvy entrepreneurship. This legacy is embodied in the Compasso d’Oro award, the most venerable and prestigious accolades in design, dating back to 1954. Initiated by La Rinascente department stores and currently curated by the ADI – Association for Industrial Design, these awards spotlight excellence in aesthetic, functional, and practical design.

Our selection highlights 9 of the most beloved and widespread items from the extensive catalog of over 350 annual awardees – pieces of exceptional design that you might just find your own.

9 everyday items that are Compasso d’Oro winners

Spanning 5,000 square meters, Milan’s ADI Design Museum is home to a collection of Compasso d’Oro award-winning designs. This exhibit traces the journey of Italian design, showcasing a range of applications, many of which are surprisingly commonplace in our daily lives.

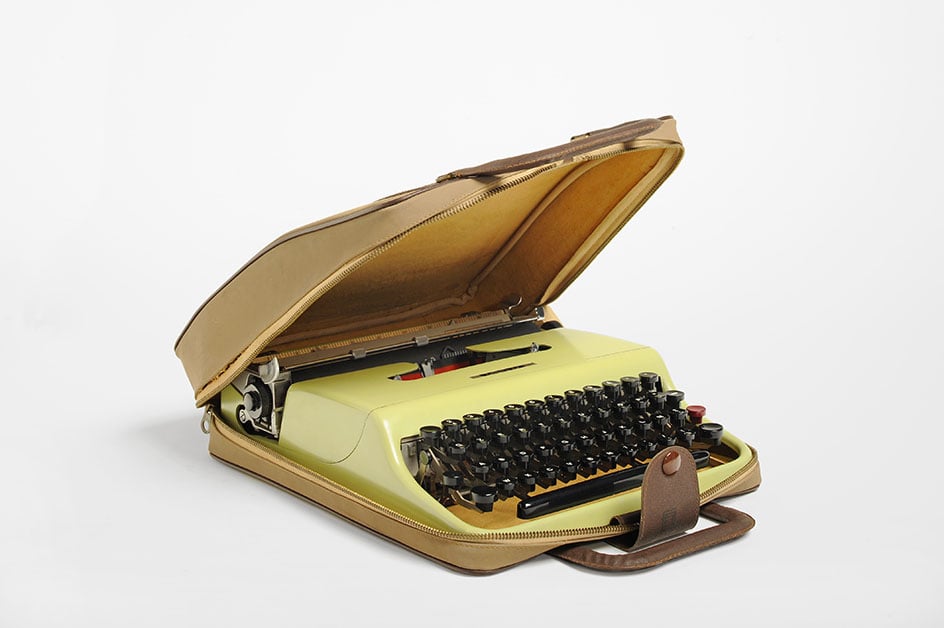

1. Lettera 22 portable typewriter

The legendary Lettera 22, designed by Marcello Nizzoli for Olivetti, rightfully earned its place among Compasso d’Oro winners. Produced in over 2 million units from 1950 to the mid-60s, the Lettera 22 set the standard for portable typewriters both in Italy and internationally.

This successor to the MP1 model was engineered for ultimate portability, cleverly integrating the keyboard and roller within its compact body, only leaving the knob and a slimmed-down line spacing lever on the outside.

Despite its reduced size, the Lettera 22 didn’t compromise on functionality. Its construction boasted durable materials and precision hammers, ensuring both robustness and a user-friendly experience.

Innovative design choices were made to minimize weight and size, such as the omission of the 1 and 0 keys, substitutable by the letters i and o. Special features were also thoughtfully included, like the automatic ink ribbon reversal, a tabulation key, and the capability to type in black, red, or stencil mode for mimeograph printing.

The Lettera 22‘s enduring global acclaim – underscored by its exhibition at New York’s MoMA – stems not only from its design but also from adept marketing campaigns and a resonant name that naturally extends the Italian alphabet.

In 1954, the ADI recognized Olivetti’s exceptional overall contribution, citing it as a paragon of stylistic consistency across all facets of production, from the graphic and promotional efforts to the architectural design of their stores, factories, homes, and customer services.

2. Mirella sewing machine

The Mirella sewing machine, another brainchild of the adept and prolific Marcello Nizzoli, is a notable icon in the sewing world.

Crafted for Necchi, a historic sewing machine company from Pavia, Mirella secured its second Compasso d’Oro in 1957. Nizzoli’s brilliance shone through as he first created the Supernova and then refined its technical features with the Mirella. Celebrated with the “Gran Premio” at the 11th Triennale in Milan and showcased in the MoMA in New York, the Mirella impressed the jury with its efficiency and shape. The latter, “inspired by contemporary non-figurative sculpture […] reveals the importance of this exemplary synergy between industry and designer”, maintaining “a true technological character”. Its expansive work base, seamlessly melded with the machine’s body, highlights a commitment to design and practicality, hallmarks of both designer’s and company’s legacy.

3. Fiat 500 automobile

Succeeding the celebrated Fiat 500 Topolino, the New Fiat 500 emerged in 1957, crafted to be Italy’s first car for the masses during the post-war economic boom. Engineer Dante Giacosa‘s vision was to create a car that not only served the working class of Italy but also stood as a beacon of Italian design on the international stage – a goal he achieved admirably. The New Fiat 500 became an emblem of Made in Italy design, hailed for its innovative features and accessibility.

Giacosa’s design was a blend of aesthetic charm and practical ingenuity. The car’s compact, minimalistic design, measuring less than 3 meters in length, housed a robust four-stroke, two-cylinder engine with an air-cooling system, offering power and efficiency within its small frame. The use of a retractable fabric roof – a cost-saving choice – added a touch of luxury previously unseen in such an affordable car.

Despite its small size, the Fiat 500 boasted a surprisingly spacious interior, a crucial detail for ensuring its popularity among families.

Equally important was the selling price.

The initial release, however, nearly stumbled – certified for just two passengers and priced close to its larger cousin, the Fiat 600. This prompted a quick pivot to a more advanced, four-seater model at a lower price point, giving rise to the “Cinquino.” This variant thrived, evolving through series until 1975 and earning a spot at the MoMA.

Giacosa’s Fiat 500 was more than just a car; it was an emblem of accessible luxury and a milestone in design, as acknowledged by the Compasso d’Oro Award in 1959, which celebrated its “important stage on the road towards a new genuine expressiveness of technique“.

4. Eclisse table lamp

The Eclisse lamp, a creation of the architect and designer from Milan Vico Magistretti for Artemide®, stands the test of time, remaining in production since its inception in 1966 and capturing the Compasso d’Oro shortly thereafter.

Ernesto Gismondi, Artemide®’s founder, commissioned a lamp that offered more than the binary on/off functionality, seeking to enhance light control in the bedroom space.

Magistretti’s stroke of genius occurred in transit; his initial vision took form on a mere subway ticket, laying the groundwork for what would become a hallmark of function and form.

The Eclisse, with its three spherical caps – a base and two semi-circular shades, one stationary and one adjustable – embodies the idea of a blind lantern described in Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables, allowing users to modulate light exposure with a simple maneuver.

Originally crafted in aluminum for its suitability to mass production, it presented a tactile challenge – the heat from the bulb made the metal too hot to touch. A design pivot introduced a plastic ring, enabling safe and comfortable adjustments.

“The Commission”, reads the ADI website, “believes that the object presented has the dual quality of high design-aesthetic value and potential mass distribution. It also highlights the novelty of the technical solution, which, with a simple rotating screen movement, adjusts the intensity of the light emitted”.

The Eclisse is also part of the permanent collection at MoMA.

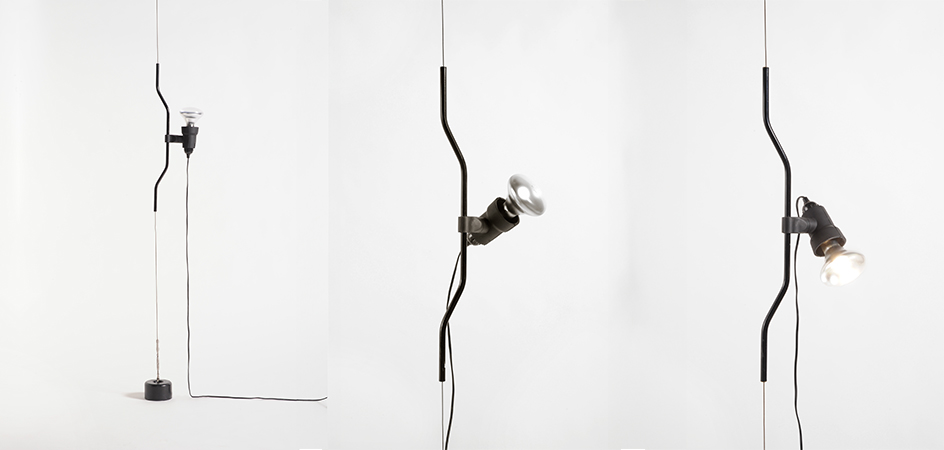

5. Parentesi lamp

In 1979, the 11th Compasso d’Oro awoke from a nine-year hiatus, honoring 42 innovative designs out of 180 contenders. Among these stood the Parentesi lamp, produced by Flos since 1971 and still available for purchase today.

The creators are among the most renowned: Achille Castiglioni and Pio Manzù, and the story behind it is even more remarkable since the two designers never met.

Manzù, known for his automotive designs including the Fiat 127, died prematurely at the age of 30 in 1969. Achille Castiglioni discovered the lamp project in Manzù’s archives and with the blessing of his widow, chose to refine it.

“I replaced the rod (envisioned by Manzù) with a metal cord, which, by being diverted, creates friction and allows the lamp to stay in position without the need for any screws”, Castiglioni would later recall. Aptly named Parentesi, Italian for “parenthesis”, the lamp features a tubular bracket that lets the light component glide along a taut steel cable, anchored from ceiling to floor. The design is as intuitive as it is ingenious, with a ceiling rose to fasten the cable above and a rubberized base below as a stabilizing counterweight.

Beyond its adjustable nature, Parentesi‘s appeal lies in its minimalist and enduring design, a testament of inclusive and widespread design that even influences its packaging. Presented as a DIY kit complete with a carrying handle, it embodies a design that’s as accessible as it is sophisticated.

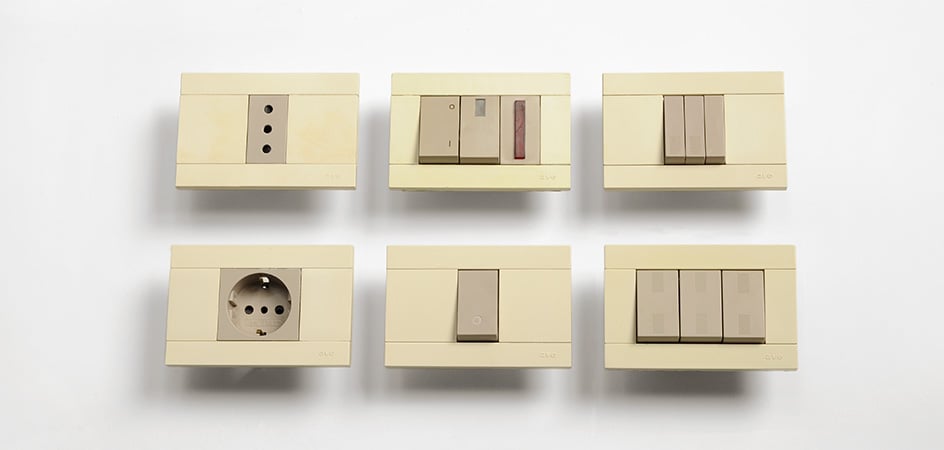

6. Habitat switches and sockets

“I want anyone who owns a switch to have a first-class design object”. This quote is from Achille Castiglioni and aligns seamlessly with the Compasso d’Oro ’79 winner for inclusive and universal design.

The award recognized the Habitat series’ first 45 mm modular switch, a line of switches and sockets crafted by Andries Van Onck and Hiroko Takeda for AVE, an esteemed name in the Italian electrical industry.

The Habitat series exemplifies how meticulous design and functionality can elevate the most overlooked items in our homes. These switches and sockets, while commonplace, are pivotal to contemporary living.

The design work by Van Onck and Takeda showcases that even daily, repetitive tasks can be revolutionized.

7. Tratto Clip and Tratto Pen marker pens

Not just a simple pen, but a writing revolution, the Tratto Pen and Tratto Clip were awarded in the Compasso d’Oro’s 11th edition. Marco Del Corno, the visionary behind Design Group Italia, joined forces with FILA Fabbrica Italiana Lapis ed Affini to bring this innovative product to life.

A Japanese patent, familiar to the company, inspired its design: a hardy synthetic tip through which water-based ink flows cleanly, free from drips and smudges, enabling writing from even the most unconventional of angles.

Attention to detail didn’t end with the ink flow; the pen’s design, including a cap with 7 teeth for a firm grip and to prevent rolling, along with holes at the cap’s end that allow air to pass through in case a child accidentally swallows it.

Leading a series of derivative products, the Tratto Clip included, the marker pen enjoyed an astounding debut, with 4 million units flying off the shelves in the first week of spring ’76. Its appeal reached the likes of Alessandro Mendini, the renowned Italian architect and artist.

Furthermore, few are aware that during the sad days of his kidnapping, the politician and former Prime Minister Aldo More received a Tratto Pen, which allowed him to write some of his letters even while lying down.

8. Mobil drawer units

In the post second war era, Kartell, under Giulio Castelli’s visionary leadership, began a profound exploration of plastic, culminating in 1999 with the distinction of being the first to craft furniture with polycarbonate.

Prior to this landmark achievement, the company had already garnered acclaim, including the prestigious Compasso d’Oro in 1994 – one of 9 they now boast – for the Mobil drawer-container system, a collaboration between Antonio Citterio and Glen Oliver Löw.

Kartell, at that time, was delving into the domestic sphere while also branching into office space design. Mobil epitomizes this transition, earning praise for injecting a refreshing, innovative style into workspaces. Its versatile and spirited design effortlessly transitioned into residential settings, presaging today’s seamless integration of home and office interiors. The ADI Jury praised Mobil‘s design, particularly noting the “exemplary interplay of the metallic structure and the vibrant, translucent plastic drawers”.

9. Sacco armchair

The Sacco by Zanotta, a piece that transcends the conventional, was honored with the Compasso d’Oro for lifetime product achievement in 2020, a testament to over fifty years of enduring allure in Italian design.

Perhaps prototyped even before it was designed, it became famous shortly after its launch. Let’s take it step by step.

It’s 1968, and three architects from Turin, Piero Gatti, Cesare Paolini, and Franco Teodoro, approach Aurelio Zanotta’s office with an idea. Or a bag. Made of jute, it mimics those filled with leaves and chestnuts used by farmers to sit on in the fields. The inception of Sacco was not just a bag but a philosophy of seating – relaxed, formless, and accommodating to the sitter’s desire for comfort without constraints.

Zanotta seized upon the concept, pioneering the use of materials that would suit mass production while maintaining the essence of Sacco‘s design: expanded polystyrene beads for the filling and durable polyester for the cover.

Dubbed nonconformist, nomadic, playful, and democratic, the Sacco armchair has graced countless spaces, from the quintessential Italian home to the prestigious halls of the Triennale Design Museum in Milan and the Victoria & Albert Museum in London. Its cultural impact is such that it has appeared in the world of Peanuts and on the silver screen in the Italian comedy Fracchia la Belva Umana.“A typological innovation in the upholstered furniture sector, it represents over time the freedom from conventional styles of use”: this is the Jury’s motivation, which recognized the full value of an armchair that, despite breaking the mold of classic seating, will never go out of style.

Are you interested in articles like this?

Sign up for the newsletter to receive updates and insights from BeCulture!

Design beyond objects

Design isn’t confined to tangible objects but is a virtuous synergy of planning, production, and aesthetic appeal that pervades our daily lives. Often unconsciously, we engage with the genius of design in forms as varied as graphic arts or architectural elements in both public and private environments. The Milan subway stands as a monumental example, having received accolades for its design and signage in 1963, crafted by luminaries such as Franco Albini, Franca Helg, and Bob Noorda.

In a contemporary context, the Gallerie degli Uffizi’s logo, created by the Carmi and Ubertis agency, was chosen by the 2020 Jury as a “synthesis of values and identity condensed into a symbolic monogram” where “simplicity and distinctiveness are the hallmarks of recognition and a deterrent to imitation”.Design, in its essence, erases boundaries, influencing every facet of our existence from our environments, the objects we use, to the ways we communicate.

This omnipresence of design is a call to observe and appreciate the details in our surroundings and serves as an inviting reason to explore the ADI Design Museum.