A supreme sculptor, an outstanding painter, Michelangelo was also an architect and writer – even though, by his own admission, he claimed he was neither. Yet he produced numerous verses in rhyme (published posthumously) and designed several buildings in both Florence and Rome. Many of his architectural projects were never even started, but among those that did take shape, we have chosen three that profoundly revolutionized traditional forms – an innovative spirit Michelangelo brought to every art form he mastered.

3 architectural works by Michelangelo worth discovering

It appears Michelangelo never studied ancient architecture in a deeply systematic way. On the contrary, his projects and buildings reflect his intent to break away from classicism and its harmonious forms. As an architect, Michelangelo strove to create dynamic, evolving works that would elicit not calm contemplation but an intellectual and emotional response – a sense of engagement or even upheaval. Forsaking balanced classical proportions, he envisioned architecture defined by varied rhythms and bold contrasts. Continuously revising and redesigning, he seldom completed what he began. Beyond his unpredictable temperament, there was also the question of the “non-finito” – a true philosophy of work for Michelangelo, most famously showcased in his Prigioni sculptures and, at least partially, in some of his larger-scale projects.

Finally, before delving into a few of Michelangelo’s most famous architectural examples, one more crucial detail: he rarely built an entirely new structure or plaza from scratch, but more often adapted existing ones, achieving results that are, perhaps for that very reason, even more astonishing.

1. Sagrestia nuova of San Lorenzo (1519-1534)

A troubled history both preceded and accompanied the development of the Sagrestia nuova in San Lorenzo, Florence. Named to distinguish it from the Sagrestia vecchia by Brunelleschi and Donatello, this project was entrusted to Michelangelo in 1520 by Pope Clement VII, following the intentions of the previous pontiff, Leone X – both members of the Medici family.

The goal was to create a space to house the remains of Giuliano, Duke of Nemours, and Lorenzo, Duke of Urbino – young heirs of the Medici line who had died only a few years earlier – as well as Lorenzo il Magnifico and his brother Giuliano.

Michelangelo adopts Brunelleschi’s same cubic structure with a hemispherical vault, replicating its dimensions exactly. Yet the interior introduces a sharp departure: instead of his predecessor’s harmonious design, Michelangelo reshapes the space in his own dramatic, intense style, multiplying and recombining classical elements in a new, almost tumultuous way. To highlight their presence, he outlines them in pietra serena, thereby creating a bold contrast with the white-plastered walls – the ideal backdrop for the monumental sculptures adorning the tombs.

For a long time, the placement of the tombs remained uncertain. Michelangelo initially considered constructing a central shrine for them, avoiding a wall-mounted arrangement. That idea – regarded with some skepticism even by the patron – was ultimately abandoned in favor of the current layout: funerary monuments for the two dukes on separate walls, facing each other, and a shared tomb dedicated to the Magnifici. Michelangelo’s own indecision wasn’t the only obstacle slowing progress.

The site faced multiple setbacks: after construction was interrupted because of the Sacco of Rome (1527) and the ensuing siege of Florence (during which Michelangelo openly sided against the Medici), Buonarroti took up the work again in 1531, only for a few years before leaving Florence for Rome. The statues, which he left unfinished, were later completed by Tribolo and Montelupo, while the chapel itself was organized, years afterward, by Vasari¹.

The sculptures of the Sagrestia nuova

Each duke’s tomb is adorned with three sculptures: the Medici’s portrait and two allegorical figures symbolizing the passage of time. Below the effigy of the Duke of Nemours – depicted as a vigorous commander, seated yet poised for action – lie Notte and Giorno. Night appears as a reclining female figure with a powerful, almost masculine torso, her head tilted in deep slumber. Around her, symbolic details (poppies, an owl, and a mask) allude to night and oblivion. Smoothly polished to a near-lustrous finish, she contrasts with Giorno, a muscular male figure who seems to have just awakened. This impression stems not only from his symmetric posture, opposed to Notte’s, with shoulders forward and face partially hidden, but also from Michelangelo’s use of the non-finito technique, leaving areas rough and not fully carved.

Meanwhile, on the opposite wall, the Duke of Urbino is portrayed in a reflective pose, gazing down on Crepuscolo and Aurora. The former appears exhausted, limbs slack, while Aurora seems to stir from nightly slumber only to discover, with sorrowful expression, Lorenzo’s death.

Thus, the overarching theme of the Sagrestia is the relentless passage of time, which fails to erase the valorous deeds and memory of these two Medici family members.

2. The Biblioteca Laurenziana (1519-1559)

We remain in Florence, home to another Michelangelo design (partially realized): the Biblioteca Laurenziana. Commissioned by Cardinal Giulio de’ Medici, who would later become Pope Clemente VII, the library was meant to house the extensive collection of books originally started by Cosimo il Vecchio and enlarged by Lorenzo the Magnificent. In fact, its conception coincided with the planning of the New Sacristy, though until 1524 – the year work began – the Pope and Michelangelo exchanged letters proposing ideas. Yet this construction, too, was prematurely left unfinished by Buonarroti, who was occupied with other commissions. It was eventually completed by other illustrious figures, including Vasari and Ammannati.

One of the most significant – and technically challenging – areas is the recetto or vestibolo. This tall, narrow space is almost entirely filled by the grand staircase leading to the reading room. The design of this stairway posed a dilemma for Michelangelo’s successors, who made repeated trips to consult the master on how to build it. By then, Michelangelo was living in Rome; he gave them scant help, pretending he couldn’t recall the details. Finally, after several attempts, Ammannati managed to obtain enough instruction to complete the staircase in pietra serena (not walnut, as Michelangelo originally intended), whose flowing shape anticipates certain solutions of the Baroque period.

Elsewhere in the hall, traces remain of Michelangelo’s innovative design. Once again, he amassed multiple classical architectural elements but freed them from their structural function. For instance, the recessed double columns don’t actually support anything, yet in the overall arrangement of shapes and decorations they convey the intense plasticity of the architecture – its almost sculptural identity.

Are you interested in articles like this?

Sign up for the newsletter to receive updates and insights from BeCulture!

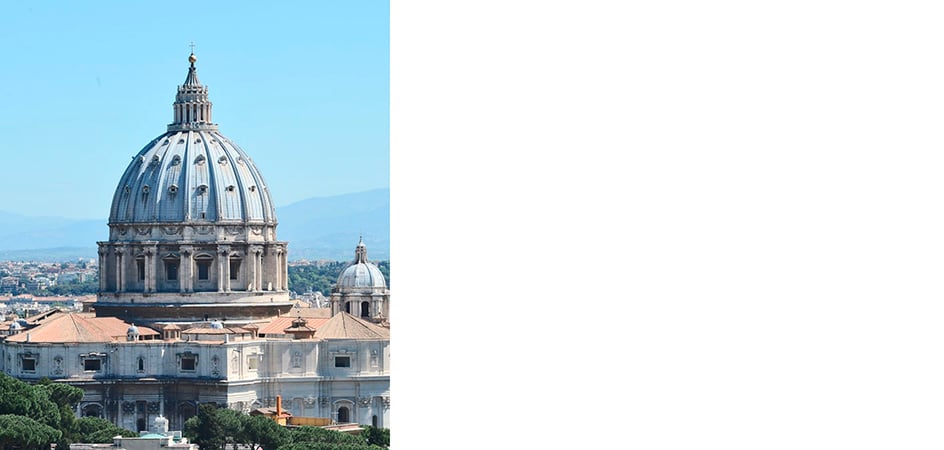

3. The Cupola di San Pietro in Vaticano (1546-1564)

The history of the Basilica di San Pietro building site is complex, so we’ll sketch it briefly to reach the moment when Buonarroti was appointed the project’s chief architect. Several masters preceded him: Bramante, chosen by Pope Giulio II in the early 16th century, then Raffaello and Antonio da Sangallo. Upon the latter’s death, Pope Paolo III named a reluctant, more than 70-year-old Michelangelo to lead the works. He thus faced the challenge of balancing earlier plans, technical needs, and the Basilica’s profound symbolic value – an aspect of great importance for a devout man like Michelangelo, especially at that historical juncture, when the Church was under the influence of the Counter-Reformation. Unfortunately, as with many of his projects, he couldn’t complete the work. The task would eventually pass to Bernini. Even so, Michelangelo’s artistic vision lives on in the Dome that crowns the Basilica and dominates the city skyline.

Though completed by Giacomo Della Porta, the dome’s overall concept and grandeur spring from Michelangelo’s design, which he oversaw for 18 years, up to the construction of the drum. Building on Bramante’s initial vision, Michelangelo drew inspiration from two further sources: the Pantheon, a marvel of classical architecture, and Brunelleschi’s dome for Santa Maria del Fiore. From Brunelleschi’s work, he borrowed the idea of a dual shell – an inner and outer dome – vital for structural stability. Yet he arranged everything so that, as Vasari writes, “seen from the ground, it looks as though it were all carved from a single piece”. Its compact, elongated shape, and the interplay of light created by windows arranged in ascending tiers (though later somewhat modified by 18th century decoration), reinvent the spatial experience and produce a dramatic new effect. These innovations once more paved the way for the art of the following era.

As we know, Michelangelo wasn’t easy to work with, and many of his projects reflect his internal unrest and conflicts with patrons and collaborators. The dome of San Pietro’s was no exception, yet fortunately, that didn’t prevent its completion. Apparently, even a fiery personality could be forgiven for someone with such remarkable architectural – and artistic – genius.

1 Artist, architect, and writer at the Medici court, and the author of Le vite de’ più eccellenti architetti, pittori, et scultori italiani, da Cimabue insino a’ tempi nostri (published in 1550 and 1568, with additions), a foundational work in Italian art historiography.