Determined, talented and tenacious, Giambologna – born Jean de Boulogne – is one of the leading figures of sixteenth-century Italy, and even today, anyone visiting Florence cannot help but admire his works. Among the most remarkable, celebrated and widely reproduced is certainly his Mercurio volante (1580, Florence, Museo del Bargello), now a true symbol of Mannerism and its daring formal balancing acts.

The Mercurio volante by Giambologna

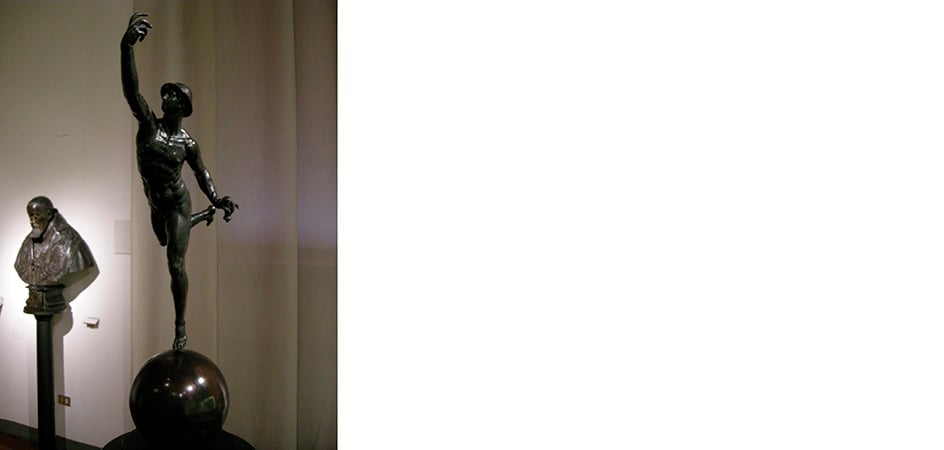

A nude youth, his body strong and polished, stretches lightly upward in a gesture that defies gravity. His right leg is raised and bent backward, echoing the elegant reach of his hand pointing skyward. His torso, supple and dynamic, twists in a graceful spiral, creating a composition of incredible movement. The entire body pivots around the left leg – the only, slender point of support – which rests with an almost unreal grace on the breath of wind-blown from the head of Zephyrus, the west wind.

This is Mercury, messenger of the gods: the winged helmet, winged feet, and the caduceus, symbol of his role between gods and men, are his traditional attributes. Yet Giambologna goes beyond mere iconography.

His Mercury floats in the air, weightless, almost immaterial – suspended between heaven and earth in an equilibrium that seems impossible, yet perfect.

The illusion of flight is rendered with extraordinary mastery: the vertical tension is perfectly conveyed through the subject’s musculature and motion, and every line of the sculpture draws the eye upward. Elegant and graceful, this work reveals the full extent of Giambologna’s skill, as he masterfully interprets the hallmarks of the late Renaissance: the serpentine form, the pursuit of height, and a flair for compositional and structural daring.

These features are also present in other masterpieces of his, such as the famous Ratto delle Sabine (1583, Florence, Loggia dei Lanzi), but here they appear with their full expressive force, amplified by the many vantage points the sculpture offers.

And as we’ll see, this power was already exercised by the Flemish sculptor in earlier versions and would continue to express in later ones – inspired by illustrious precedents.

Patronage, precedents and copies

The Mercurio volante kept at the Museo del Bargello was created in 1580 for Cardinal Ferdinando de’ Medici and was intended for the Medici villa in Rome, as the crowning element of a fountain whose basin made from a bowl of green Egyptian breccia.

But this was not the artist’s first attempt at depicting an airborne Mercury. The initial commission in this long and successful series did not come from the Medici circle.

We know that Jean de Boulogne arrived in Italy around the age of twenty and went straight to Rome to study classical antiquities first-hand. He later moved to Florence, where he came into contact with the Florentine nobility and gained recognition for his marble and bronze sculptures, as well as his fountains.

It was, in fact, a public commission that brought him to Bologna in 1563. Papal vice-legate Pier Donato Cesi tasked him with creating the Fontana del Nettuno, designed by architect Tommaso Laureti, as part of Pope Pius IV’s urban renewal plan.

During this work, which still stands today in the city’s main square, Giambologna received another commission from Cesi – this time for the Archiginnasio, home to Bologna’s prestigious university. According to Cesi’s words, a “bronze image of Mercury descending from the heavens” was to be placed “in the centre of the courtyard on a vermiculated stone column” – a symbol of reason and divine truth, a reminder to students.

The project was never completed, though a model survives at the city’s Civic Museum.

Still, Jean did not abandon the idea. In fact, the Mercurio volante was highly appreciated by Cosimo de’ Medici, who in 1564 commissioned a version roughly the size of an adolescent boy to be sent as a diplomatic gift to Maximilian II of Habsburg, Emperor and brother of Joanna of Austria, betrothed to his son Francesco de’ Medici. It also pleased Cosimo’s other son, the second Grand Duke of Tuscany – the aforementioned Ferdinando I – who in 1598 sent a copy to the King of France, Henry IV (often identified with the bronze now held at the Louvre in Paris). The versions multiplied – today examples can be found in museums in Dresden and Vienna – with formal variations that increasingly emphasised lightness and movement, aided by the addition of Zephyrus’s breath, which heightens the sense of upward, aerial projection.

Possible sources of inspiration

The Greek god captured in the act of flying was not an entirely new subject, and Giambologna clearly drew from several sources. One of the most likely is the Mercurio painted by Raffaello in the early 1500s in one of the pendentives at Villa Farnesina in Rome.

But it is from Cellini that the young Flemish sculptor inherited the fluid quality that defines the sculpture, which seems to hover in mid-air and transcend the limits of its material: Cellini’s own Mercurio (1552–1553), originally housed in one of the niches of the Perseo base and now preserved at the Museo del Bargello, proves the point.

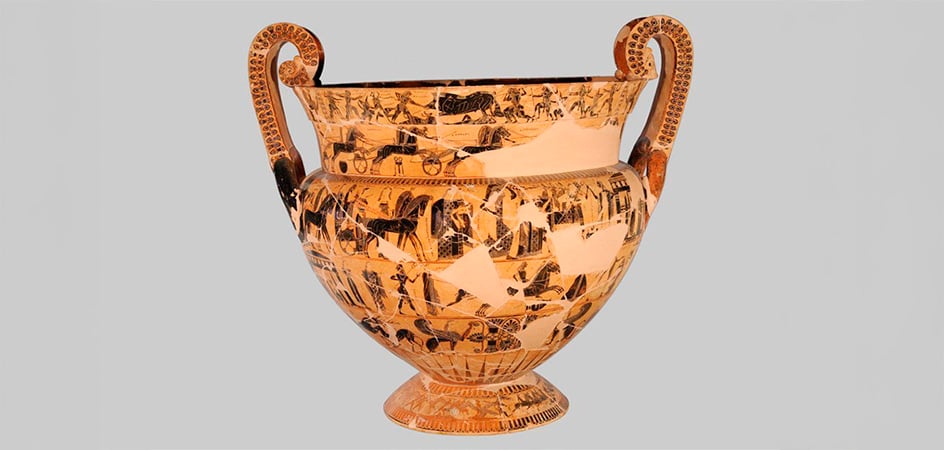

An immortal technique

Over time, the Medici family’s esteem for Giambologna grew to the extent that he became a salaried artist and, around 1567, he was allowed to set up his workshop in the second courtyard of Palazzo Vecchio.

By 1587, he moved his studio to Borgo Pinti and, at the height of his fame, began employing assistants capable of reproducing his wax models in bronze. In the Renaissance, the preferred technique for creating bronze works was lost-wax casting, which involved making a wax model, covering it with a mould, melting the wax, and pouring molten bronze into the resulting cavity. This delicate method required great skill and experience and is still used today by some of the most prestigious fine art foundries – including the Fonderia Artistica Ferdinando Marinelli in Florence.

Are you interested in articles like this?

Sign up for the newsletter to receive updates and insights from BeCulture!

Giambologna’s small bronzes soon became highly sought-after collector’s items – a clever way to meet the vast demand for his work from nobles and rulers far and wide. Otherwise, it would have been nearly impossible to satisfy all requests, given the volume of commissions from the Medici alone.

Simone Fortuna, ambassador in Florence for the Duke of Urbino, once wrote a letter to his lord – eager to obtain a marble work from the artist – strongly suggesting that he instead settled for a bronze, quicker to produce but just as beautiful.And indeed, who could argue with that? Slender, graceful and ethereal, the Mercurio volante – and its many variants – clearly display the overwhelming talent of a visionary, innovative artist who has long commanded admiration.