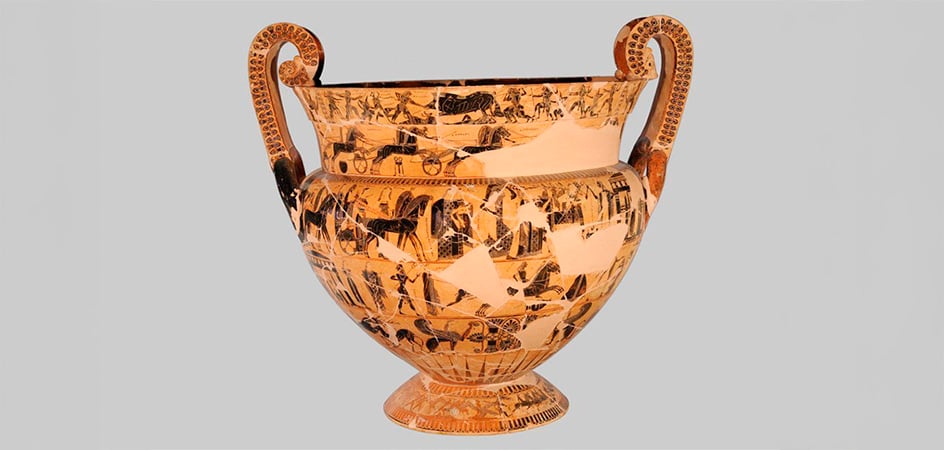

Manufatto eccezionale, il vaso François è una testimonianza rara e preziosa della produzione di ceramica attica. Talmente rara e talmente preziosa che qualche studioso ha proposto di ribattezzarlo Rex vasorum, Re dei vasi. Merito della sua forma insolita e dalle magnifiche scene dipinte che lo decorano interamente. Dinamismo e staticità, solennità e pathos struggente si alternano in quest’opera unica, che porta ancora i segni di una storia fortunata e a tratti rocambolesca.

La travagliata storia del “Re dei vasi”

Il vaso François prende il nome dall’archeologo fiorentino Alessandro François (1796-1857) che tra il 1844 e il 1845 ne rinviene i numerosi frammenti nella necropoli etrusca di Fonte Rotella, in provincia di Chiusi, parte della tenuta medicea di Dociano. Il ritrovamento è straordinario. Il sito in cui si trova – sotto dodici metri di terra – è incredibilmente vasto: con un’ampiezza pari al diametro esterno del Colosseo, è la più grande tomba da camera di età arcaica a noi nota. Nonostante fosse già stata depredata in passato, al momento della scoperta conserva ancora i grani di una collana d’oro, la testa di una tigre di marmo con le fauci spalancate e molti vasi greci ed etruschi. Appare subito chiaro che il “Gran Vaso” – come lo chiamerà François – è un esemplare dell’arte vascolare greca tra i più antichi e sofisticati mai visti in Italia.

Realizzato nel VI secolo a.C. dal vasaio Ergotimos e dipinto dal pittore Kleitia – le loro firme sono visibili su entrambi i lati – giunge a Chiusi in circostanze sconosciute. La ceramica greca era molto apprezzata dagli aristocratici etruschi e altri manufatti simili erano arrivati qui prima di questo. Tuttavia, questo particolare cratere (vaso per la mescita di acqua e vino) doveva godere della massima considerazione, tanto da essere incluso tra i beni del nobile sepolcro.

Poco dopo essere stato scoperto, viene acquistato da Leopoldo II Granduca di Toscana ed esposto prima nel Gabinetto dei Vasi Etruschi delle Gallerie degli Uffizi di Firenze e poi nel Museo Archeologico di via della Crocetta, dove ancora oggi si trova. Ma la sua è una storia tutt’altro che ordinaria: il ritrovamento è infatti solo l’inizio.

Il danneggiamento, il furto e il frammento ritrovato

Le tracce di piombo ancora visibili in alcuni punti della decorazione rivelano che il vaso François aveva subito una prima rottura e riparazione in passato, anche se non è possibile dire se ciò sia accaduto in Grecia o già in Italia. Sappiamo però con certezza quando avviene il secondo e ben più eclatante danneggiamento dell’opera.

È il 9 settembre 1900, è domenica e il museo è aperto al pubblico. Giuseppe Maglioni, custode del museo con disturbi psichici pregressi, afferra uno sgabello di legno del peso di quasi 5 kg e lo scaglia con violenza contro la vetrina che protegge il vaso, frantumandolo. Solo pochi minuti prima aveva ferito con un coltello il Caposervizio del museo – che rimarrà in ospedale diversi giorni – e distrutto altre opere in un moto d’ira scatenato da una lite per questioni di lavoro.

Al danno si aggiunge però anche la beffa: durante i disordini causati dall’incidente un visitatore sottrae, non visto, un frammento del vaso. Il pezzo verrà restituito in forma anonima qualche anno dopo – lasciato dentro un vaso del Museo Egizio – a seguito dell’accorato appello del direttore dell’Archeologico su una rivista specialistica.

Al momento della restituzione, nel 1903, il vaso però era già stato già restaurato ricomponendo non solo i 638 cocci provocati dal Maglioni, ma aggiungendo anche il cosiddetto frammento Strozzi. Questo frammento, sebbene fosse pervenuto da tempo nelle collezioni archeologiche, non era mai stato integrato nel cratere.

Nel 1866, infatti, il marchese Carlo Strozzi aveva donato alle Gallerie degli Uffizi un pezzo del vaso sfuggito ai primi scavi e ritrovato da un contadino (che il marchese aveva suggerito di ricompensare con l’assunzione a custode del museo, mai avvenuta).

Bisogna quindi attendere il nuovo restauro del 1973 perché anche il frammento rubato venga rimesso al suo posto e il vaso possa finalmente (ri)mostrarsi in tutta la sua straordinaria bellezza.

L’apparato iconografico e il suo significato

Anche se non è il più grande cratere attico a figure nere su fondo terracotta – come viene spesso affermato per errore – il vaso François è sicuramente uno dei più affascinanti e controversi. Le sue 131 iscrizioni, comprese le doppie firme dei suoi autori, non lasciano dubbi sulle 270 figure rappresentate, eppure il loro significato è ancora oggetto di studio e interpretazione.

Le principali scene dipinte sul lato A

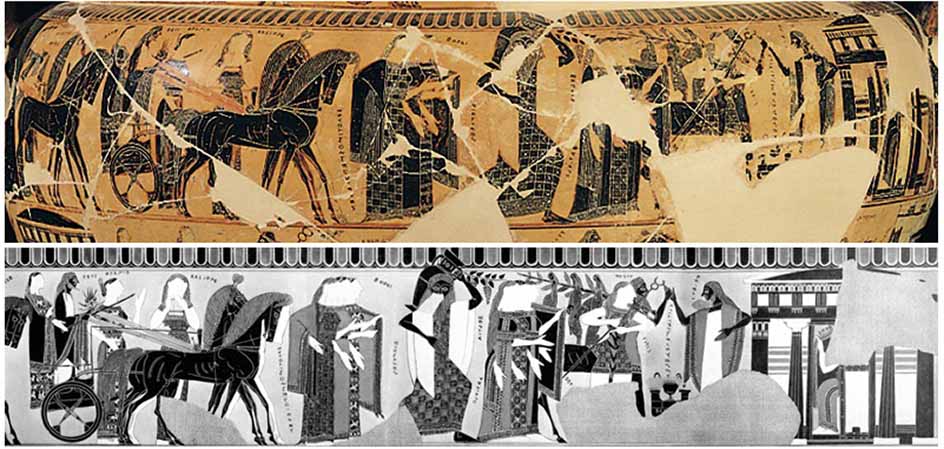

Il fregio principale si sviluppa nel punto di massima larghezza attorno ai due lati del vaso, chiamati A e B e raffigura il corteo per le nozze di Peleo e Teti, futuri genitori del grande eroe greco Achille. La sposa, appena visibile a causa delle lacune del vaso, siede all’interno di un sontuoso palazzo delimitato da un’anta bianca, dove si vede un particolare curioso: una piccola apertura rettangolare, una “gattaiola”, per il passaggio dei ricci domestici, usati per tenere lontani serpenti e topi. Lo sposo accoglie gli invitati fuori, davanti a un altare, e stringe la mano al centauro Chirone. Da questo gesto nasce la firma verticale del pittore, “Kleitias mi ha dipinto”. Dietro di loro, nelle quadrighe, si susseguono i più importanti dei dell’Olimpo e altre figure a piedi. Dal muso del cavallo che trasporta Zeus ed Era discende l’autografo del vasaio: “Ergotimos mi ha fatto”.

Senz’altro la figura più enigmatica è quella di Dioniso, dio del vino, rappresentato al centro del fregio con un’anfora sulle spalle. I dettagli curatissimi, come il volto barbuto e l’abito finemente decorato, e l’altezza spropositata (arriva persino a toccare il margine superiore del fregio!) sembrano indicare il ruolo di primo piano nella scena, anche se l’interpretazione non è ancora certa.

Richiami ad Achille, alle sue gesta e quelle di suo padre sono presenti negli altri ordini del vaso, sempre su questo lato. Sull’orlo del cratere riconosciamo la Caccia di Calidonio, il cinghiale ucciso da Peleo; e subito sotto i giochi funebri per la morte di Patroclo, amico fidato di Achille. Nella fascia sottostante il fregio principale, assistiamo all’uccisione di Troilo, figlio minore del re di Troia, da parte dell’eroe greco durante il famoso assedio: basta la posa tesa e il piede sollevato di Priamo, avvisato del terribile evento, per trasmetterci tutta l’angoscia del momento.

La morte di Achille è invece rappresentata per ben due volte, in modo speculare, all’esterno delle due anse.

Gli episodi mitologici del lato B

Questo lato è dedicato a un altro eroe della mitologia greca: Teseo. Partito per Creta per uccidere il Minotauro, il mostruoso uomo-toro che ogni anno divorava quattordici giovani ateniesi inviati come tributo, riesce nell’impresa anche grazie ad Arianna – figlia del re di Creta e sorellastra del Minotauro – e al suo famoso filo. Il bordo superiore del vaso racconta, in una sequenza temporale complessa, proprio questo episodio. Da sinistra a destra riconosciamo dunque la nave con i fanciulli festanti (e, sopra di loro, le altre due firme degli artigiani del vaso); la danza delle gru, ballo rituale degli ateniesi istituito da Teseo a Delos, nel viaggio di ritorno, per celebrare la vittoria sul mostro; e l’incontro tra l’eroe, mentre suona la lira, e Arianna, che gli porge un gomitolo.

Nell’ordine sottostante si consuma invece la Centauromachia, la battaglia dei Lapiti contro i Centauri alla quale partecipa lo stesso Teseo. Infine, sotto al fregio centrale viene narrato il fastoso ritorno di Efesto all’Olimpo, un episodio molto diffuso nell’età arcaica.

Animali e altre figure

Creature reali e fantastiche occupano i registri inferiori di entrambi i lati, raffigurati con precisione calligrafica ed estro, carichi di simbolismi ancora indecifrabili ma dal sicuro effetto scenico. È il caso anche delle due Gorgoni alate presenti nelle volute, verso l’interno del vaso. Una posizione probabilmente studiata per far sì che, quando il cratere era colmo, i due mostri si rispecchiassero sulla superficie liquida, dando l’idea di volare sopra al “mare color del vino”, per usare le parole di Omero.

Ma questi non sono gli unici animali del vaso François: nel piede riconosciamo infatti la battaglia tra gru e Pigmei (detta Geranomachia), che si sviluppa in modo continuo per tutta la circonferenza. I piccoli uomini in groppa ai caproni affrontano con coraggio le terribili gru che devastano ogni anno i loro raccolti. Eppure, al confronto con le altre battaglie rappresentate, questa ha qualcosa di grottesco, come se Kleitias abbia voluto stemperare con una nota più leggera – persino tragicomica – il tono intenso e drammatico dell’opera.

Sei interessato ad articoli come questo?

Iscriviti alla newsletter per ricevere aggiornamenti e approfondimenti di BeCulture!

Possibili interpretazioni

Le interpretazioni critiche, lo dicevamo, sono tante e tutte plausibili. Secondo alcuni, il filo conduttore è il tema nuziale, legato forse a una commissione in occasione di un matrimonio importante; altri invece vi hanno visto un’esaltazione della figura maschile e della forza dell’intelletto umano contro la forza bruta, simboleggiata dagli animali.

Altri ancora ritengono si tratti piuttosto delle fasi tipiche della vita di un giovane ateniese: dall’iniziazione, alla guerra, al matrimonio; e c’è chi sostiene infine che le scene principali dei due lati siano un confronto esplicito tra un eroe panellenico (Achille) e uno tipicamente ateniese (Teseo). Nessuna di queste teorie è sicuramente giusta o sbagliata e anche questa ambiguità contribuisce al fascino di questo clamoroso reperto.

Il recente riallestimento della sala del Museo Archeologico Nazionale, con riproduzioni retroilluminate e in grande scala su fondo nero, permette ai visitatori di osservare da vicino le minuziose decorazioni del cratere. Incantevole per gli appassionati di archeologia e di mito greco, il vaso François è una fonte inesauribile d’ispirazione anche per chiunque si interessi di grafica e d’illustrazione: le sue soluzioni formali originalissime e l’equilibrio compositivo unico travalicano il tempo, rendendole attuali ancora oggi.