He was the master of the Ferrarese Renaissance, yet his memory was lost for centuries, and even today we know very little about him and his training. Cosmè Tura – a multifaceted artist at the Este court during the second half of the fifteenth century – managed to blend the courtly taste of Gothic art with the innovations of Tuscan painting, creating a personal and distinctive style that would become a model for others to follow.

Let us retrace the life of this major figure of Italian art through some of his most celebrated masterpieces.

Youth and his appointment at the Este court

Within the geography of Renaissance cultural centres, Ferrara stands out as a unique case. Its artistic rise was the result of a deliberate and systematic programme, which began under Niccolò II d’Este and continued with his successors Alberto V, then Leonello and, above all, Borso. This was a dynasty committed to the deliberate creation of a vibrant cultural hub financed directly by the local lords – one that would reflect their prestige and rival the other great Italian courts. The monumental castle at the city’s centre, the new university, and the presence of distinguished intellectuals and artists from across Europe (including Pisanello, Jacopo Bellini, Andrea Mantegna, Rogier van der Weyden, and Piero della Francesca) all bear witness to this ambition for greatness.

In this climate, around 1430, Cosimo di Bonaventura – known as Cosmè Tura – was born to a shoemaker father. Little is known about his youth, but it is highly probable that, owing to his evident artistic talent, he was sent between 1453 and 1456 to study in Padua, in the workshop of Francesco Squarcione. This same workshop also trained Mantegna (his contemporary) and many other painters of the mid-fifteenth century, all influenced both by the persistence of late Gothic solutions and by the sculptural revolution of Donatello, who was then active in the Venetian city.

Tura managed to reconcile this dual influence with the demands – or, one might say, the whims – of his main patrons, the Este family, who hired him as official court painter in 1458 and retained him until 1486.

Vestments, decorations for festivities, frames, gilding, banners, the “palio” for the winner of the donkey race, garments, furniture, blankets, tapestry cartoons, designs for tableware and much more: Cosmè’s workshop produced far more than paintings. It crafted everything the court might require, as confirmed by payment records from the time. These works were often ephemeral (very few have survived to this day), yet they help explain, at least in part, the painter’s highly tactile and material style.

Cosmè Tura’s style through 3 selected works

To anyone viewing the rare surviving works of the Ferrarese master, their chromatic, compositional and graphic originality immediately stands out – unlike anything else in Renaissance painting. His distinctive style was passed on to his assistants and successors, yet when the Este court moved to Modena at the end of the sixteenth century, this artistic language was lost, and Tura’s legacy fell into near-total oblivion for a long time (even Vasari¹, in his Vite, barely mentions him, dedicating only a brief note within the chapter on Niccolò Baroncelli). It was not until the eighteenth and, more decisively, the nineteenth century that this great personality of Italian art was rediscovered. His innovative strength was later appreciated by Symbolist and Expressionist artists of the historical Avant-Garde, who praised his expressive power. This renewed interest made it possible to recover studies and information about his art, now represented by a few but eloquent masterpieces.

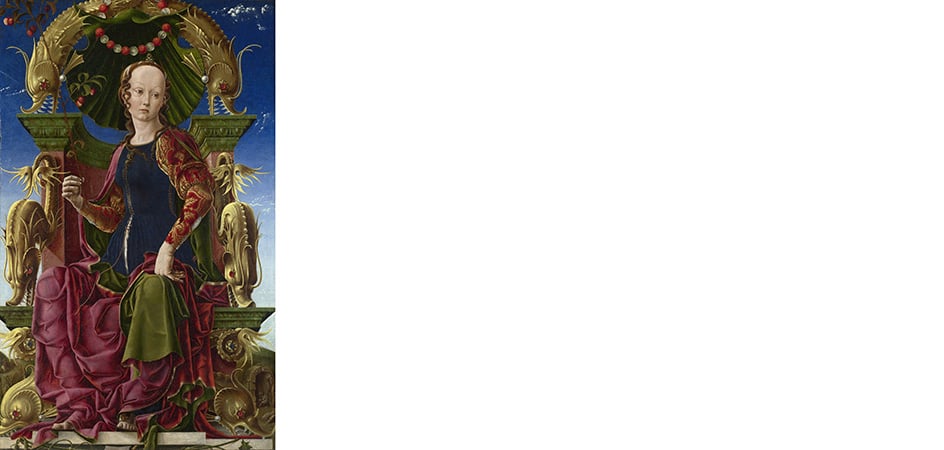

The Primavera (c. 1460)

Commonly known as La Primavera (London, National Gallery), the work in fact depicts one of the Muses painted by Tura for the decoration of the Este studiolo of Belfiore, which was later dismantled following the decline of the Este lordship over the city. Solemn and imposing, Tura’s Muse occupies the entire panel with angular plasticity. A throne supported and surmounted by six sea monsters adds to the painting’s unsettling atmosphere. The sharp folds of her gown, enriched with gold-embroidered sleeves, give the volumes a novel harshness. The decorative taste Tura had acquired during his Paduan years – visible, for instance, in the garland above – is here counterbalanced by a monumentality reminiscent of Piero della Francesca. The result, however, is a figure far removed from the serenity of the Aretine master: mysterious and sharp-edged, metallic both in colour and in modelling.

Infrared analysis has further confirmed the artist’s mastery in perfectly handling the oil technique, demonstrating that he was well acquainted with the results achieved in the same years by his Flemish contemporaries.

But who is the Muse portrayed? The interpretation of the painting’s symbols has allowed scholars to identify her as Calliope, the Muse of Poetry. The cherry branch and the marine creatures were, in fact, associated with justice – a theme often linked to poetry itself.

San Giorgio e la Principessa and the Annunciazione (c. 1469)

The organ shutters of Ferrara Cathedral are perhaps Cosmè Tura’s most famous work and reveal his full creative flair. They consist of four canvases, paired two by two, now preserved in the Museo del Duomo in Ferrara. The panels depicted different subjects, visible to the faithful depending on whether the organ was open or closed. When open, they showed the Annunciazione: the kneeling angel on the left and the praying Virgin on the right. Both figures are set within a grand architectural framework, frozen in sculptural poses, their garments clinging tightly to their bodies as if forged by a blacksmith. The tranquillity of the scene is enlivened once again by Squarcionesque “interferences” (the fruit-laden draperies above, and the gilded bas-reliefs on the walls) and by the naturalistic additions in the background – a bare landscape where a bird and a squirrel stand out.

When the panels were closed, the tone changed dramatically: the enigmatic tension of the biblical meeting gave way to open violence and drama, verging on the paroxysmal. Saint George, protector of the city, rears up on his frenzied horse, striking down the dragon beneath him. The dynamism of the gesture, the knight’s impetuous determination and the creature’s terrified expression are among the artist’s most powerful inventions, along with the princess on the adjacent panel. The young woman flees in terror – arms raised, mouth wide open in a scream – almost defying the weight of her heavy dress, which billows in thick folds. The precious jewellery she wears betrays her noble rank and reflects the Este court’s love for the decorative arts.

The scene, a quintessentially courtly theme, is thus reinterpreted with an exaggerated and gripping dynamism, a testament to the artist’s fertile imagination.

The polittico Roverella (1474)

The pinnacle of Cosmè Tura’s eccentricity was arguably reached with the Polittico Roverella, named after its commissioner, Bishop Lorenzo Roverella.

Originally displayed in the church of San Giorgio fuori le mura in Ferrara, the work was partially destroyed by an explosion in the early eighteenth century. Today, it is divided among several museums worldwide, including the Louvre in Paris and Palazzo Colonna in Rome.

The National Gallery in London houses the central panel with the Madonna col Bambino. Tall and narrow, it develops vertically through a striking invention: an imposing stepped throne decorated with a richly adorned backrest, set within a niche defined by strict perspective. Everything seems to stretch upward, including the Virgin herself, elongated almost to excess, her slightly tilted head counterbalancing the gentle slump of the Child she holds in her lap. Completing this dense composition is a host of musical angels, whose white and green robes echo the tones of the surrounding architecture.

Here again, Tura’s mimetic quality is heightened and vigorous: this is clearly visible in his imitation of the throne’s marble and metal materials, and in the solid drapery enveloping the figures.

Are you interested in articles like this?

Sign up for the newsletter to receive updates and insights from BeCulture!

Unlike other polyptychs painted by the Ferrarese master, this one is among the most complete and easiest to reconstruct, although some gaps and uncertainties remain. Scholars are still debating, for instance, the exact placement of three roundels depicting episodes from the life of Christ, now housed in three different museums in the United States but clearly sharing stylistic coherence.

Tura’s frescoes, however, are entirely lost. He probably took part – if not as an executor, at least as artistic director – in the magnificent Cycle of the Seasons at Palazzo Schifanoia, also in Ferrara. We can only imagine how many other shades of his iron-like, expressive, Gothic yet Tuscan language we might have admired.

1. Giorgio Vasari (1511–1574), artist, architect and writer at the Medici court, was also the author of Le vite de’ più eccellenti architetti, pittori, et scultori italiani, da Cimabue insino a’ tempi nostri (published in 1550 and expanded in 1568), a foundational text in the history of Italian art.