Wunderkammer, cabinets de curiosités, chambers of wonders: from the late Renaissance onwards, this is how domestic spaces devoted to the gathering and display of natural specimens, artefacts and curious objects came to be known. Mysterious and fascinating places, they expressed a unique form of scientific collecting, from which today’s natural history museums derive, while also inspiring later artistic movements such as twentieth-century Surrealism.

The precursors of cabinets of curiosities: Italian studioli

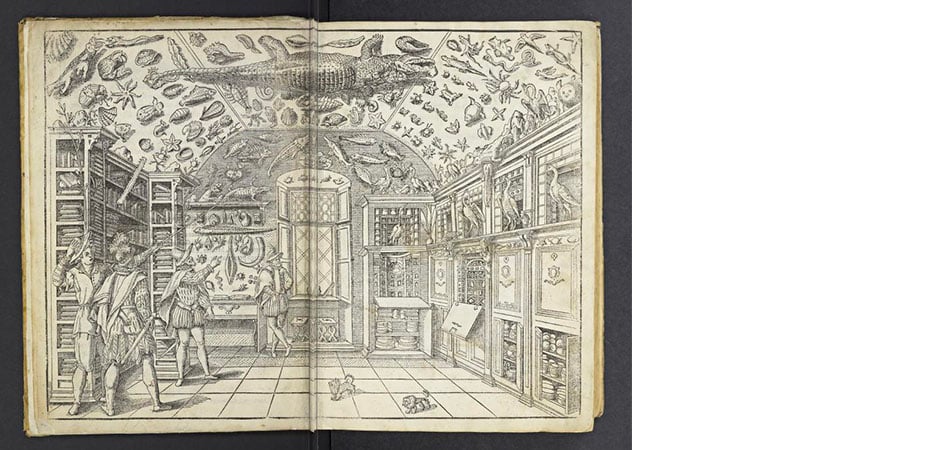

In the Historia naturale by the apothecary Ferrante Imperato (Naples, 1599) we find a woodcut depicting a group of four men gazing – with evident wonder – at the walls of a peculiar room. This is the earliest known representation of a cabinet of curiosities: the walls filled with books, containers, vases, botanical and animal specimens up to the ceiling, which in turn is covered with shells and marine creatures, including a giant stuffed crocodile. A dizzying excess and yet somehow ordered, as everything is arranged to be viewed or studied up close (note, for example, the display cases on the right).

The intellectual enrichment and delight of the owner lay at the heart of the first Wunderkammer, which emerged in northern Italy in the late fifteenth century under the name studioli. Set up in princely palaces, these studioli were small spaces, often secluded from the rest of the residence. Here works of art and human ingenuity, as well as natural curiosities, were kept for the contemplation of the ruler and a select circle of friends. Among the most notable studioli of the period were that of Lionello d’Este (1407–1450) at Palazzo Belfiore near Ferrara; the Florentine one of Pietro de’ Medici (1414–1469), later inherited by Lorenzo the Magnificent; and that of Federico da Montefeltro (1422–1482) in the Palazzo Ducale of Urbino.

The spread and meaning of the Wunderkammer

The origins of these rooms, however, go back even further, to the reliquaries of medieval churches. These collections could include relics associated with Christ and his disciples, but also unusual fragments such as remains of the Virgin’s milk. According to common belief, relics held miraculous power and were therefore carefully preserved and displayed only on special occasions. That same aura of magic and wonder was later transmitted to the secular cabinets of curiosities, which spread across Italy and the rest of Europe.

In German-speaking lands, the word Wunderkammer (“chamber of wonders”) gained currency from 1550, alongside Kunstkammer (“art chamber”). By the end of the sixteenth century the two terms had merged into Kunst-und-Wunderkammer, encapsulating the eclecticism of these spaces.

Although not untouched by the phenomenon, the French and English courts showed less interest in such collections, which were based precisely on the coexistence of man-made and natural objects, especially if unusual or hybrid. Collecting, defining and classifying were the principles on which, spurred by the humanist thirst for knowledge, the Wunderkammer arose and multiplied beyond royal palaces. Between the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, this activity also involved clergymen, scholars, universities and institutions, as well as members of the aristocracy and the bourgeoisie – among them particularly apothecaries and physicians.

Artificialia and naturalia: cabinets of curiosities between art and nature

Collectors sought to investigate and interpret reality in all its forms, tracing analogies and connections between its various manifestations. This is why these rooms overflow with objects and yet, at the same time, are organised according to a precise display and aesthetic logic that favoured affinities and symmetry: the rarest, most unique specimen placed at the centre, surrounded by secondary pieces, often stored in precious cabinets and containers.

A fine example of this type of “art cupboard” (Kunstschrank, in German) is preserved at Uppsala University: a miniature gallery of art and mirabilia, created in 1632 by Philipp Hainhofer as a diplomatic gift from the city of Augsburg to Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden during the Thirty Years’ War.

Naturalia and artificialia – “things” of nature and of man – thus crowd the Wunderkammer, taking on new value and wonder either through their juxtaposition or by virtue of their sheer strangeness. Over the years, the pursuit of unique, extravagant and even monstrous artefacts and specimens intensified.

A concentration of life (and death)

Cabinets of curiosities were characterised by a myriad of objects (naturalia, artificialia, curiosa, exotica…) chosen according to the interests and personality of their owner – sometimes leaning towards the natural sciences, sometimes towards human artifices, or even towards the symbolic and the prodigious.

Among the most common were:

- minerals, valued both for their scientific significance and for their appearance, often enhanced by superb craftsmanship such as Florentine commesso;

- shells, seen as evidence of extinct life and greatly admired by Mannerists; they were often turned into luxury artefacts or ingeniously displayed, as in the four busts preserved in the Treasury of the Grand Dukes at Palazzo Pitti, in Florence. The Medici were great shell enthusiasts, as also shown by the marvellous ceiling of the Tribuna degli Uffizi;

- corals, skeletal remains of animal creatures resembling plants, which fascinated collectors with their threefold nature, further emphasised by artistic craftmanship and virtuosity;

- coloured wax models, metal casts or papier-mâché: representations of reality that create convincing illusions of life or parts of living beings, including humans;

- imaginary creatures, such as monsters, dragons and mermaids, for which – in the impossibility of distinguishing between reality and fiction – evidence was fabricated in various materials and sizes, in order to heighten the sense of strangeness;

- anomalies and deformities, animal or human, real or mythical, preserved in jars or illustrated;

- ivory artefacts, bold geometric compositions and masterpieces of extraordinary skill, such as the one preserved in the Treasury of the Grand Dukes at Palazzo Pitti;

- automata and self-moving machines, midway between nature and artifice, life and death, often in the form of bizarre creatures. The Castello Sforzesco in Milan still preserves the Automa con la testa di diavolo, made between 1590 and 1610, probably designed by its owner, Don Manfredo Settala (1600–1680). Still partly functioning, the mechanism made the head, eyes and teeth move, stick out the tongue and grin monstrously, leaving viewers deeply unsettled.

And beyond these: antiquities, clocks, fossils, bezoars, unicorn horns, mummified limbs, bones, skulls… anything that might foster research or provoke astonishment, often with a taste for the macabre and the esoteric.

Are you interested in articles like this?

Sign up for the newsletter to receive updates and insights from BeCulture!

Manfredo Settala: a notable example of Baroque collecting

Ulisse Aldrovandi (1522–1605), Francesco Calzolari (c. 1521–c. 1606) and Ferrante Imperato (c. 1525–c. 1615) are just some of the most famous Italian collectors, each with his own line of thought and merits. But here we should highlight another figure, already mentioned, who epitomises the spirit of Baroque collecting: the canon Manfredo Settala.

Author of one of the most remarkable cabinets of curiosities – conceived by him as an image of the world and containing more than three hundred pieces – Settala also delighted in constructing scientific devices. He was an expert in ivory and astronomical instruments, which he valued more for their aesthetic qualities than for their practical use.

His originality was evident in his unusual way of cataloguing reliquaries: not by the saint they contained, but by the materials with which they were made.

A true source of local pride, on his death he was celebrated with great pomp by the townspeople, who accompanied the coffin in procession while carrying his most eccentric and unusual objects.After his death, Settala’s gallery was dispersed among various museums in the city – a fate shared by many Wunderkammer. Yet the strength of their legacy has not been lost and, even today, thanks to the surviving objects kept in galleries, we can still grasp – albeit on a smaller scale – that sense of enigmatic wonder which filled those extraordinary spaces.