Madness, with its medical, physiological and social implications, is one of the most complex subjects to define. Broadly understood as a deviation from what is considered “normal” (another concept that is equally wide-ranging and uncertain), it has long attracted the attention of intellectuals, scientists and artists. The latter, in particular, have portrayed it through different forms and approaches, which vary according to the period and the sensitivity of each artist.

Precisely because the manifestations of madness are manifold – and the interpretations just as numerous – this article focuses on some of the most well-known and still meaningful examples today, dating from the period between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance.

Madness as the open sea: dark and unknown

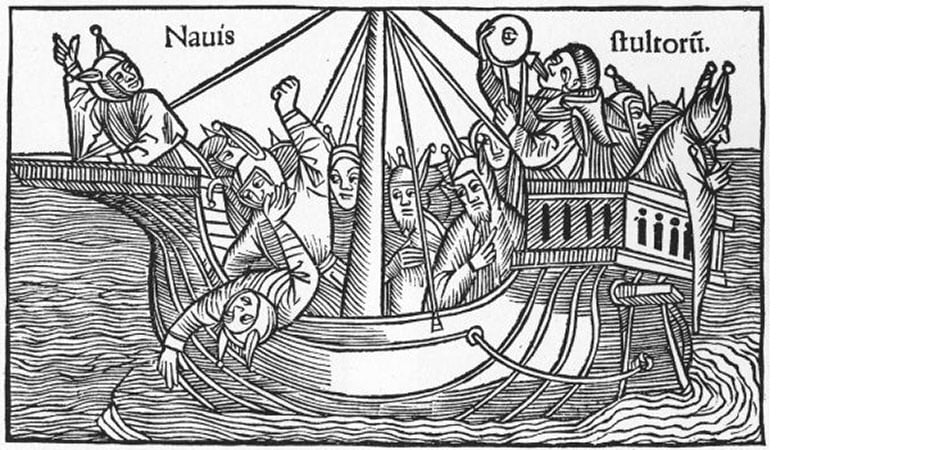

Madness has long been associated with the image of the sea: a mysterious expanse of water, driven by untamed forces, dangerous and shifting between uncontrollable emotional surges and sudden moments of withdrawal. La nave dei folli, a satirical work by the German humanist and poet Sebastian Brant (1494), accompanied by engravings largely produced by Albrecht Dürer, offers an ironic yet didactic vision of this idea. In the poem, 112 categories of fools embark together to travel to Narragonien, the Land of fools. A tragic fate awaits them and, after passing through the Land of Cockaigne, they will drown miserably without ever reaching their destination. The engraving that opens the text is precisely that of a Navis stultorii: a ship without a helmsman, led by men at the mercy of their own desires and oddities.

However, the madness Brant speaks of is not only that of mental disorder, but rather that of all human beings who, in his view, appear ridiculous before God. This is why, among the various types of fools, he includes the elderly, the clergy, gossips, and parents. All figures whose supposed normality is, in truth, nothing more than a disguise — a pretence.

Carnival: when madness takes the stage

Speaking of disguise and make-believe, Carnival is perhaps the most eloquent symbol of madness. According to some reconstructions, this popular celebration may derive from the Babylonian rite of the Car Navale, the “naval chariot” that floated from the temple of Borsippa (emblem of the sky) to that of Babylon (emblem of the earth). It was a moment of transition, suspended between two worlds, in which light and order on the one hand, and darkness and irrational chaos on the other, could blend together. Once again, the image is that of a vessel on the verge of shipwreck — the same vision painted by Hieronymus Bosch in his celebrated Nave dei pazzi (c. 1490–1500, Louvre, Paris).

The scene, lively only in appearance, is wrapped in a sombre atmosphere. On a dark and unfathomable sea drifts a small boat, now entirely adrift. On board, a curious group of figures engages in unusual actions: a nun, with an enchanted, almost hallucinatory expression, plays while attempting to bite a pastry suspended from the ship’s mast. Other mouths reach for the coveted morsel: that of a priest with a vacant stare (perhaps a case of senile dementia); of a rower gazing into emptiness; and of a man who, seized by ecstasy, cries out and gestures wildly. The inability to obtain fulfilment or satisfaction — typical of those who experience an “other” mental state and are therefore excluded from social life — is perhaps symbolised by the food. Alongside the hanging pastry we see cherries, objects of desire and frustration for the two figures in the boat, and a chicken tied high up on the mast, made almost impossible to reach. On the right, however, two other figures are worth noting: a man overcome with nausea recalls depictions of the Underworld, where the soul of the damned collapses into a terrible act of vomiting. Just above him, the fool (which in English also means “madman”) sips something in a thoughtful pose, as if reflecting on his own condition of imprisonment and on that of the others. His staff, known as a marotte, bears a replica of his own face — a possible allegory of narcissism, but also of the necessary (and perhaps futile) search for the self.

The Feast of Fools and the (temporary) reversal of social order

The same grotesque ambiguity between euphoria and sorrow can be found in other traditions, such as the Feast of Fools. Also known as the “Feast of the Donkey”, the “Feast of Children”, the “Feast of Deacons” or the “Feast of the Innocents”, it was celebrated throughout the Middle Ages and disappeared during the sixteenth century.

According to tradition, in the days between the old and the new year, the lower clergy and the common people would exchange roles in a playful and excessive celebration: priests and friars danced dressed as women, children, animals and fools, often in an obscene or inappropriate manner. At the same time, the poorest classes and marginalised individuals would wear ecclesiastical garments and elect their own “Fool’s Pope”. A true overturning of social roles, where it becomes possible to break free from worldly constraints and give full rein to one’s exuberance.

An effective depiction of this moment is Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s engraving La festa dei folli, dated 1561 (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York). On closer inspection, within the confusion of bodies, faces and objects, we can distinguish several figures dancing, playing music, pulling faces, somersaulting and performing other bizarre gestures. It depicts an actual celebration held in Antwerp in the same year, following a recurring pattern in the Low Countries known as Sotte Bollen. In Flemish, the term Sottebol means “fool with a ball shaped head”, an association that derives from a local proverb suggesting that fools are recognised by the way their heads roll about foolishly.

The Charivari: burlesque ritual against transgression

It is possible that the Feast of Fools derived from the Saturnalia, ancient pagan celebrations based on the same mechanism of role reversal. But the analogies with other similar rites do not end there. One need only think of the Charivari, the French term for the masquerade held in the Middle Ages on the occasion of a widower’s second marriage, considered insolent and transgressive. During the night, young men in disguise staged pranks and revels, often obscene and offensive, aimed at the groom. A delirium, a collective madness intended to exorcise the primal impulse of those who choose to marry again. In the Roman de Fauvel, composed between 1310 and 1314 by the cleric Gervais du Bus, Fauvel (the protagonist, a man with the head of a horse or a donkey) embodies the sum of all vices. His figurative transpositions are numerous, from fifteenth-century illuminated manuscripts to later paintings, such as Titania and Bottom with the donkey’s head — inspired by Shakespeare — painted by Henry Fuseli (1793–94, Kunsthaus, Zürich). Another curious link between the Roman de Fauvel and madness is the presence of Hellequin: the celebrated Arlecchino of the Commedia dell’Arte, described by some as a true demon, whose cunning tricks could drive people to lose their reason, provoking reactions of instinct and anguish.

Are you interested in articles like this?

Sign up for the newsletter to receive updates and insights from BeCulture!

Faces of madness: between laughter and suffering

A similar condition is expressed even more explicitly and powerfully in the so-called medieval “grilli”: figures reduced solely to the face, captured in grimaces and ambiguous attitudes. The face condenses the entire body into itself, conveying the full intensity of emotions associated with psychosis: masks frozen into distorted smiles, capricious expressions, gestures that are childlike yet deeply unsettling. Examples can be found in numerous Romanesque and Gothic churches, such as the Cathedral of Aosta, where among others we can distinguish Un folle, Un uomo selvatico e Un demone acrobata (G. Vion de Samoen and G. de Chetro, 1469).

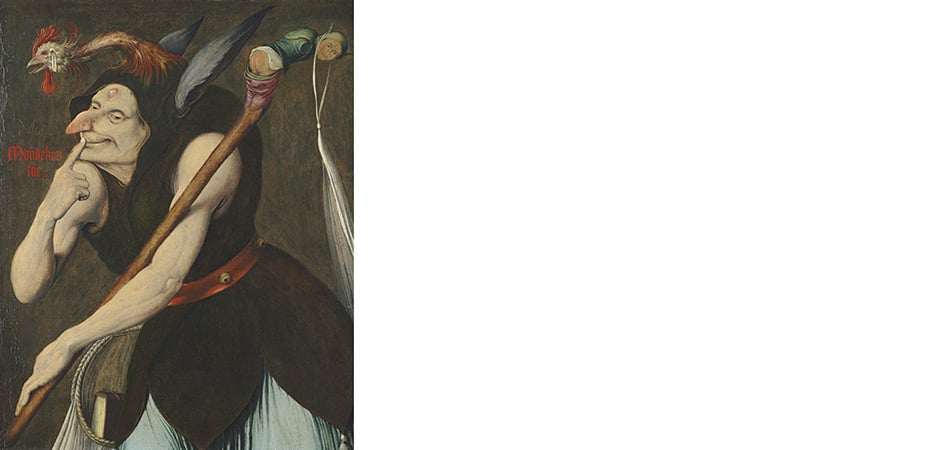

The overwhelming and almost animal intensity of madness is difficult to contain and, often, impossible to express. The difficulty of articulating one’s inner state or impulses in words is a defining feature of many sixteenth-century representations in which madness appears silent, or speaking into the void. This is clearly illustrated in Quentin Massys’ Allegoria della follia (c. 1510), now in a private collection in New York. The artist, known for having created one of the most famous portrayals of ugliness in the world, depicts here a deformed female figure wearing a donkey-eared fool’s cap topped with a cockerel and holding an obscene marotte, as she raises a finger to her lips as if searching for words—or preventing them from escaping. Her smile, far from being friendly, seems to foreshadow a bitter outcome: a sorrowful admission of a distorted inner reality.

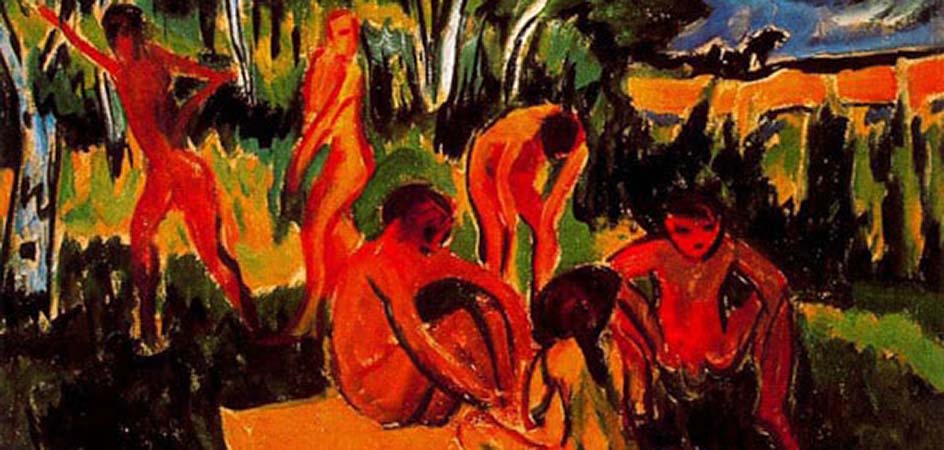

Gesture, as well as animal-like expression, are recurrent devices in the iconography of anguish and mental disturbance, even in later periods. To cite only a few examples: Egon Schiele often entrusted the hands with the task of conveying turmoil, while Antonio Ligabue expressed his uncontrollable emotions and childhood trauma through the depiction of wild beasts.Madness, understood as a lack of self-control and a departure from the norm, is a fertile and multifaceted artistic theme — perhaps precisely because it draws upon an indecipherableand mutable subject: the human mind and its capacity to cross the boundaries of reason, sometimes without return. There is perhaps no enquiry more unsettling and compelling than this, for who, indeed, could claim to be entirely immune to the wild and senseless flights of the imagination?