The Galleria Palatina is one of the museums housed in Palazzo Pitti, the former grand ducal residence in the heart of Florence. Located on the piano nobile of the building, alongside the Royal and Imperial Apartments, it preserves today a collection of paintings that is unique in the world—an outstanding example in the Italian panorama for its layout, which has remained virtually unchanged since the 18th century.Masterpieces by Raffaello, Tiziano, Bronzino, Rubens, and Caravaggio (to name but a few) line the walls of its magnificent rooms, adorned with stuccoes, gilding, and frescoes: a testament to the refined taste of Medici collecting and the subsequent Lorraine administration.

History of the Galleria Palatina

The Galleria Palatina was established between the late 18th and early 19th centuries at the behest of the Habsburg-Lorraine family, who succeeded the Medici as Grand Dukes of Tuscany.

Anna Maria Luisa de’ Medici (1667–1743), the last heir of the historic Florentine dynasty, died childless but had stipulated in her will that the family’s patrimony should remain in the city. Thus, when the Lorraine family came to power, they found themselves in charge of an extraordinary collection of artworks and antiquities, distributed between the Galleria degli Uffizi and Palazzo Pitti.

Under their guidance, a significant effort was made to reorganise and curate the picture collection, allocating some of the most important paintings from the Medici collection to this purpose.

The collection had begun in the 16th century under Cosimo I and by the 17th century already included several paintings that would later enter the Gallery—among them La Velata by Raffaello, the Ritratto di Pietro Aretino by Tiziano, and the Ritratto di Luca Martini by Bronzino. But it was Ferdinando de’ Medici (1663–1713), Grand Prince of Tuscany—an accomplished cellist and art connoisseur—who considerably enriched the holdings. Upon his death, he left nearly a thousand paintings in his apartments at Palazzo Pitti.

By the late 18th century, the most celebrated masterpieces were already located in the Sale dei Pianeti (Halls of the Planets), named after the astrological frescoes painted between 1640 and 1647 by Pietro da Cortona for Ferdinando II de’ Medici as symbols of princely virtues (Venus for benevolence, Apollo for splendour, Mars for strength, Jupiter for royal majesty, Saturn for prudence).

The arrival of Napoleonic troops in Florence marked a temporary halt to the Lorraine’s reordering efforts.

Are you interested in articles like this?

Sign up for the newsletter to receive updates and insights from BeCulture!

The French entered the city in 1799, forcing the Grand Duke into exile in Vienna. During the Italian campaign, 63 paintings were seized and stripped of their frames, which remained forlorn on the walls. In anticipation of a second French incursion—indeed realised in 1801—artworks, furnishings, vestments, and other valuables were hidden in cupboards and secret rooms within Palazzo Pitti, in an effort to save as much as possible.

During the short-lived Kingdom of Etruria (1801-1807)1, attempts were made to fill the gaps left by looted paintings using works from the Corridoio Vasariano and the villas of Castello and Petraia.

With the end of the Napoleonic era, Antonio Canova was appointed by Pope Pius VII to recover the works of art that had been taken during the French occupation, and so the Florentine masterpieces also returned to the city—some in very poor condition, such as San Marco by Fra Bartolomeo, which required several restoration interventions.

The following years saw further updates to the arrangement of the picture gallery, and in 1919 Palazzo Pitti was donated to the State.

5 Masterpieces from the 15th Century to the Baroque Era

The Galleria Palatina offers visitors an astonishing display: a feast of paintings, lavishly framed, covering the walls of numerous rooms furnished with Florentine commesso tables, mirrors, sculptures, vases, and fine tapestries. The painted and decorated ceilings open onto allegorical scenes of sublime beauty, completing the museum’s decorative richness. Here are five masterpieces, spanning from the Renaissance to the Baroque, that exemplify the splendour of this collection:

The Tondo Bartolini by Filippo Lippi

Master to Botticelli (of whom several works are on display), Filippo Lippi painted this tondo between 1452 and 1453, likely for the wealthy merchant Leonardo Bartolini Salimbeni. The round painting depicts a Madonna and Child with scenes from the life of Saint Anne and is notable both for its size—one of the largest from the early Renaissance—and for its original composition. In the foreground, the Virgin is seated on a throne holding the Child, who is eating pomegranate seeds, symbolising fertility and foreshadowing the Passion. Behind them unfold episodes from the life of Saint Anne: the meeting with Joachim (on the right) and the birth of Mary (on the left), with Anne surrounded by women offering care and gifts.

The varying size of the figures gives a sense of depth but also conveys the temporal sequence of events—from distant and small to recent. The whole scene is unified by the setting: a 15th-century interior that perfectly reflects the tastes of a wealthy contemporary household.

The Madonna della Seggiola by Raffaello

The Galleria Palatina houses the largest concentration of works by Raffaello in the world, from both his Tuscan and Roman periods. The Madonna della Seggiola (Madonna col Bambino e San Giovannino), displayed in the Sala di Saturno, owes its nickname to the distinctive piece of furniture that replaces the traditional throne. But the seat is not the only novelty in this tondo, painted around 1512, likely for a high-ranking Roman cleric. What strikes the viewer is the intense intimacy of the scene, the tenderness with which the Mother embraces her Son while resting in the elegant chair. The young Saint John gazes at them, forming a triangle of looks that directly engages the viewer. Here Raffaello blends his soft style with Michelangelo’s lessons from the Sistine Chapel. Thus, the sweetness of the gesture—seen by some as almost too human—is balanced by the sculptural quality of the figures, emphasised by their forms and drapery. The result is a strikingly original composition that makes full use of the round format.

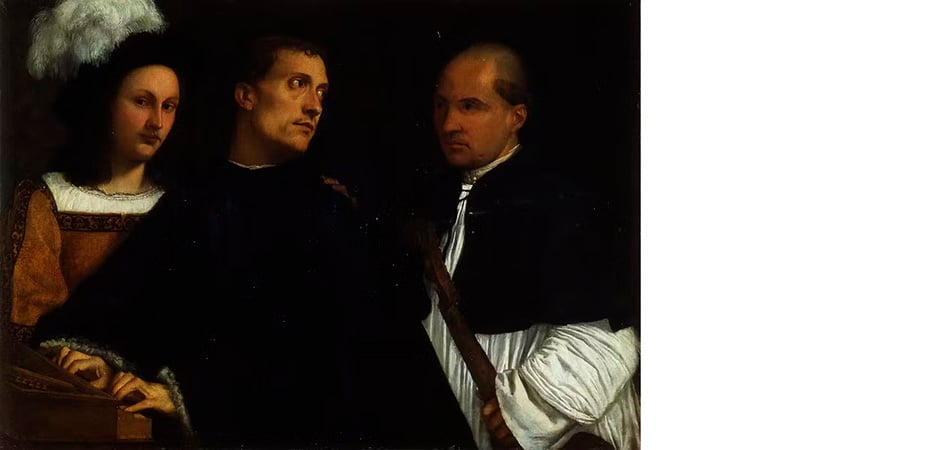

The Concerto by Tiziano

Passion for Venetian painting was common among many Medici descendants, notably Cardinal Leopoldo (1617–1675), whose inventory listed 130 Venetian paintings out of 800. The Concerto was acquired in 1654 as a work by Giorgione, an attribution that held until the 20th century, when the painting was correctly credited to Tiziano. The canvas, painted around 1610, depicts a spinet player in the foreground, a singer to the left, and a viola da gamba player to the right. The latter rests his hand on the central figure’s shoulder, who turns to look at him, while the youth in the feathered hat glances sideways at the viewer.

Though the subject was common in late Renaissance Northern Italian painting, this didn’t prevent curious interpretations. Upon Leopoldo’s death, the painting was dubbed Lutero, Calvino e la Monaca—a misreading based on faded colours and shifting fashion. According to this interpretation, the spinet player—whose secular clothing had become difficult to discern—was thought to represent Luther, with Calvin behind him, and alongside them the nun Katharina von Bora, Luther’s wife (her attire was reminiscent of a woman’s garment, hence the gender ambiguity). This theory was later dismissed following the painting’s restoration.

Today, it is generally believed to be a portrait of musicians who were well known in Tiziano’s time—namely the Flemish composer Philippe Verdelot and his pupil Obrecht—whom Vecellio places in a calm and intimate setting.

Santa Maria Maddalena by Artemisia Gentileschi

A powerful painting, both in its subject and in its deep connection to the artist’s life. Santa Maria Maddalena (ca. 1620) by Artemisia Gentileschi portrays one of the most popular themes of the 16th century with a truly unique emotional intensity. The young woman—dressed in a sumptuous yellow gown—is captured at the moment of her conversion: her hair dishevelled, one hand on her chest, the other covering a mirror (a symbol of vanity) inscribed with Optimam partem elegit (“She has chosen the better part”), referencing her embrace of virtue. Maria Maddalena is bathed in a beam of light from above—a clear Caravaggesque device that heightens the drama. Some believe the work was commissioned by Maria Maddalena of Austria (1589–1631), wife of Cosimo II de’ Medici (1590–1621), and that the saint’s face is a self-portrait.

Just a few years earlier, Gentileschi had survived a violent assault and the harrowing trial that followed. In Florence, she gained the support of elite families and became the first woman admitted to the Accademia delle Arti e del Disegno. Like the saint she painted, Artemisia chose the better and redemptive part of herself, beyond the harm she endured.

Giuditta con la testa di Oloferne by Cristofano Allori

Giuditta con la testa di Oloferne (1610–1612) is the most renowned work of Florentine painter Cristofano Allori and reveals the influences of Caravaggio and Artemisia Gentileschi. This is especially clear in the arrangement of the figures and the use of light: a pronounced chiaroscuro that enhances the dramatic impact of the scene. The theme, widespread since the Renaissance (aided by Donatello’s sculpture), depicts the biblical heroine Judith beheading the Assyrian general Holofernes, with the assistance of her elderly maid. Judith is portrayed as strikingly beautiful, with her delicate features and rich clothing in stark contrast to the horror of the severed head she holds. A beauty that is real rather than ideal, since – according to some – the painting portrays Mazzafirra, the artist’s lover, while the face of Holofernes is said to be a self-portrait of the painter himself.

Regardless, Allori masterfully fuses aesthetic refinement and emotional impact, creating a painting of great power and allure.

Beyond these masterpieces, countless other works await in the grand and ornate rooms of the Galleria Palatina—an unparalleled heritage that makes every visit a truly unforgettable experience.

1. The Kingdom of Etruria was established to replace the Grand Duchy of Tuscany by Napoleon Bonaparte following the Treaties of Lunéville (9 February 1801) and Aranjuez (21 March 1801). The throne was assigned to King Louis I of Bourbon, son of Duke Ferdinand, as compensation for having renounced the Duchy of Parma and Piacenza, which had been annexed by France.