Casa Manzoni combines the charm of a historic residence with the documentary function of a museum. The Milanese home of the great writer from 1814 until his death, it preserves some rooms in their original layout and devotes others to telling the story of the man, the writer, and his work. A rich and recently updated exhibition route—following a project by Michele De Lucchi’s architecture studio—guides visitors through the life and legacy of one of the most significant figures of 19th-century Italy.

Alessandro Manzoni and his family within the walls of Via del Morone

It was October 1813. Manzoni had returned from Paris and was living in Milan, surrounded by his loved ones: his young wife Enrichetta Blondel, whom he married in 1808 when she was just sixteen; his mother Giulia Beccaria, daughter of the renowned Cesare Beccaria and also known as Donna Giulia; and his first two children, Giulietta and Pietro. When he purchased the townhouse at Via del Morone 1171 (today no. 1), the family was thrilled. The building required substantial modernisation, but the Manzonis lacked the necessary funds. Still, after carrying out the most urgent renovations, they moved in and enjoyed a lively family and social life. The house was ideal for hosting friends and notable figures such as Massimo d’Azeglio and Claude Fauriel, all in an atmosphere of warm intimacy. The large drawing room overlooking the garden comes to life during sociable evenings filled with conversation and games, such as blind man’s buff, organised by Enrichetta for the older children.

The study on the ground floor also faces the garden. A secluded spot near the servants’ quarters and bounded by the courtyard, it’s where Alessandro could meet guests, read, and write in peace while daily life bustled upstairs. It is in this very room that he began the first draft of Fermo e Lucia, which later became I Promessi Sposi (The Betrothed), the historical novel that contributed to making Manzoni the man “who brought great honour to Italy”, as Giuseppe Garibaldi would say upon meeting him in 1862.

Domestic harmony was, however, shattered in 1833 by the death of Enrichetta, his beloved wife with whom he had nine children—left prematurely without their gentle and caring mother.

In 1837, Manzoni remarried Teresa Borri, who brought fresh vitality and new habits into the household along with her son, Stefano Stampa. The kitchen became active once again, serving both the family and their guests, and even Manzoni would occasionally make hot chocolate using a recipe he had learnt in France. Not everyone welcomed the change. The memory of Enrichetta was still vivid, and comparisons between the two women were inevitable—especially for Giulia Beccaria, who did not hide her displeasure. Vittoria, Manzoni’s sixth child, also resented her stepbrother for what she perceived as inappropriate attention. Nonetheless, the couple remained strong, united by a sincere and deep affection, as shown in some of Manzoni’s writings after Teresa’s death in 1861.

Personal joys and professional recognition were always interwoven with grief and loss in Manzoni’s life. Only two of his children, Vittoria and Enrico, outlived him when he died in Milan on 22 May 1873.

The Museum route

It is always fascinating to visit the places where great figures of the past lived and worked, imagining them in their domestic settings, engaged in everyday tasks. Unfortunately, changes in ownership following Manzoni’s death altered the house’s original layout. Nevertheless, Casa Manzoni succeeds in evoking the writer’s daily life through a captivating and well-designed museum route.

The first two rooms: family and portraits

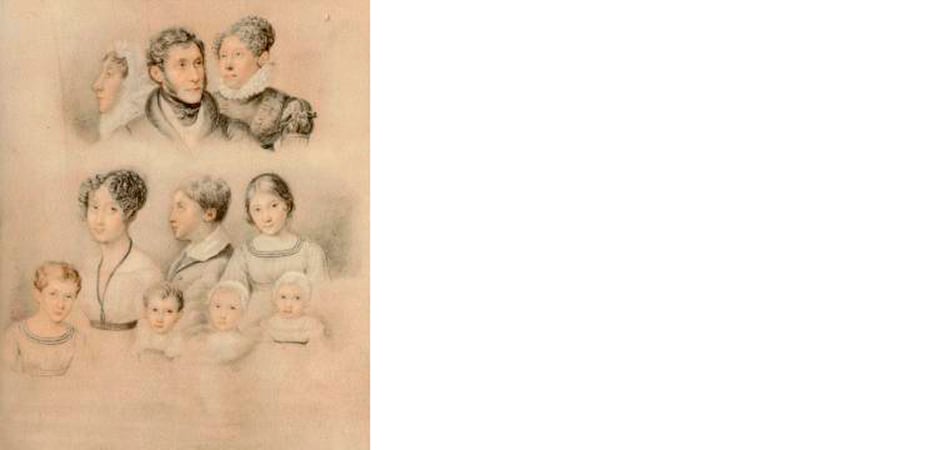

The first two rooms are dedicated respectively to Manzoni’s portraits and family. This allows us to piece together key details about the author’s rather complex past: he spent a long time away from his biological mother, whom he was happily reunited with in adulthood. In a pencil and pastel portrait on paper by Ernesta Bisi Legnani (c. 1823), Alessandro is pictured in profile alongside Donna Giulia and his wife Enrichetta. Also depicted are seven of their children: Giulietta, Pietro Luigi, Cristina, Sofia, Enrico, Clara (who died on 1 August of that same year), and Vittoria. Thanks to this and other works on display, we are able to put faces to the various family members.

The second room focuses on Manzoni’s own image. Although he was always reluctant to be portrayed, he could not entirely prevent unauthorised images of himself from circulating. Notable exceptions include the painting by Giuseppe Molteni and Massimo D’Azeglio (1835, Milan, Biblioteca Nazionale Braidense) featuring the Lake Como background, and the portrait by Francesco Hayez, commissioned by his stepson Stefano Stampa (1841, Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera). Manzoni agreed to sit for both portraits. Stefano also produced one of the most successful drawings of his stepfather, shown in three-quarter view with an introspective expression. He inscribed it: “18 October 1848, in two rainy hours… Certified likeness A. Manzoni”.

The Promessi Sposi and the illustrations in rooms III and IV

I Promessi Sposi (The Betrothed), Manzoni’s most famous work, has always enjoyed critical and artistic success, inspiring painters and sculptors. Among the most notable is the series of frescoes by Nicola Cianfanelli, created between 1834 and 1837 in the Royal Apartments of Palazzo Pitti for Grand Duke Leopold II of Tuscany, a great admirer of Manzoni.

Room III features paintings, sculptures, and illustrations inspired by the novel, often centred on its most iconic scenes, such as Lucia’s farewell to the “mountains rising from the waters”. Particularly striking is the series of lithographs by Gallo Gallina, published by Ricordi between 1827 and 1828, known for their historical detail and richness.

The following room explores the influence of Teresa Borri, a cultured and refined woman who had developed long lasting friendships with artists and illustrators during her years in Paris. She is credited with enriching the household’s library—many of those volumes (travel books, novels, often illustrated) are now on display. Among them are French satirical publications such as La Caricature e Chiavari.

The Bedroom and the Study

The only two rooms that have come down to us intact are the bedroom—Room V, at the midpoint of the visit—and the study, which is the final room (Room X).

The modest bedroom, furnished with only the essentials, was Manzoni’s own: a single bed, which was enough for him, a walnut and yellow marble table, a few armchairs, a small chest of drawers, and not much more. Above the fireplace hung a mirror, upon which, as reported by a witness in 1873, rested “two brushes, one for the beard and one for the hair”.

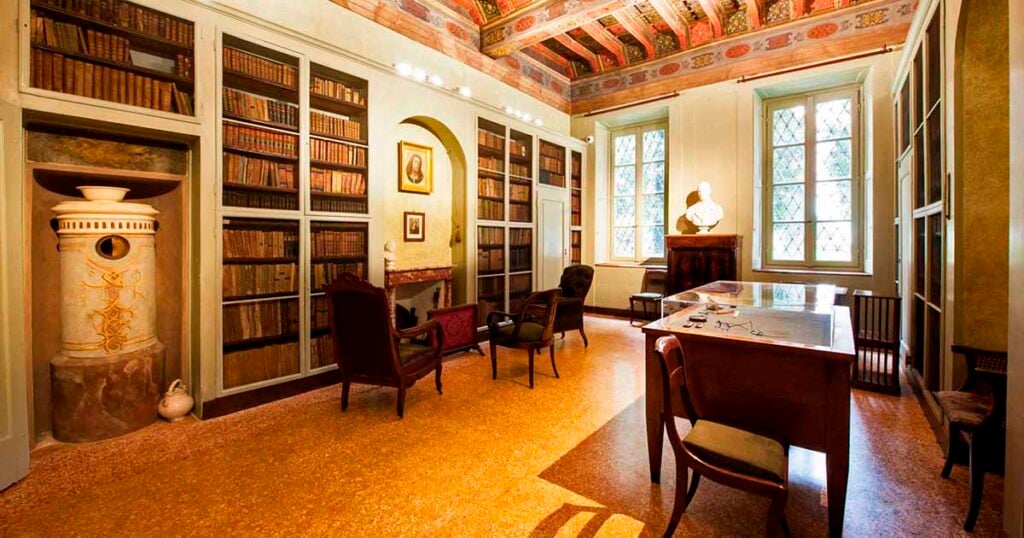

The study is slightly more formal but equally simple, with bookshelves and paintings on the walls. Opposite the desk—the writer’s favourite spot—stands a fireplace flanked by two mismatched armchairs. The large windows overlook the private garden, and it is easy to picture Manzoni gazing out, lost in literary or botanical thought.

A passion for botany: Room VII

Room VII reveals a lesser-known side of Manzoni—his keen passion for gardening and botany. Like many Lombard gentlemen of his time, he was a knowledgeable agronomist, particularly during his stays in Brusuglio, at the villa inherited by his mother from her companion Carlo Imbonati. There, Manzoni would spend his days reading, studying new horticultural techniques, raising silkworms, and experimenting with crops such as hemp and cotton. Paintings and artefacts in the Casa Manzoni collection confirm this lifelong interest, which also finds expression in the moving natural descriptions found in his most famous novel.

Are you interested in articles like this?

Sign up for the newsletter to receive updates and insights from BeCulture!

The Other Rooms

Manzoni’s life and interests are further extensively explored in the remaining rooms, arranged as follows:

- Room VI: first editions, writings and various works that illuminate the greatness of the author and the evolution of his thought during the years from the Restoration to the political unification of Italy;

- Room VIII: inspired and fascinated by the natural world, Manzoni in turn influenced landscape painting. Many contemporary works reflect the balance of realism and sentimentality found in his writing;

- Room IX: this room is dedicated to friends, with portraits of close companions including Tommaso Grossi, Manzoni’s lifelong friend, frequent guest, and long-time occupant of the room opposite his study.

With its well-structured route and understated, harmonious layout, Casa Manzoni offers a comprehensive portrait of its distinguished resident: not only as a celebrated writer and public figure, but also as a son, father, and husband—an emotional, affectionate man, as well as a man of intellect.