Home / Experience / Sandro Botticelli

Sandro Botticelli

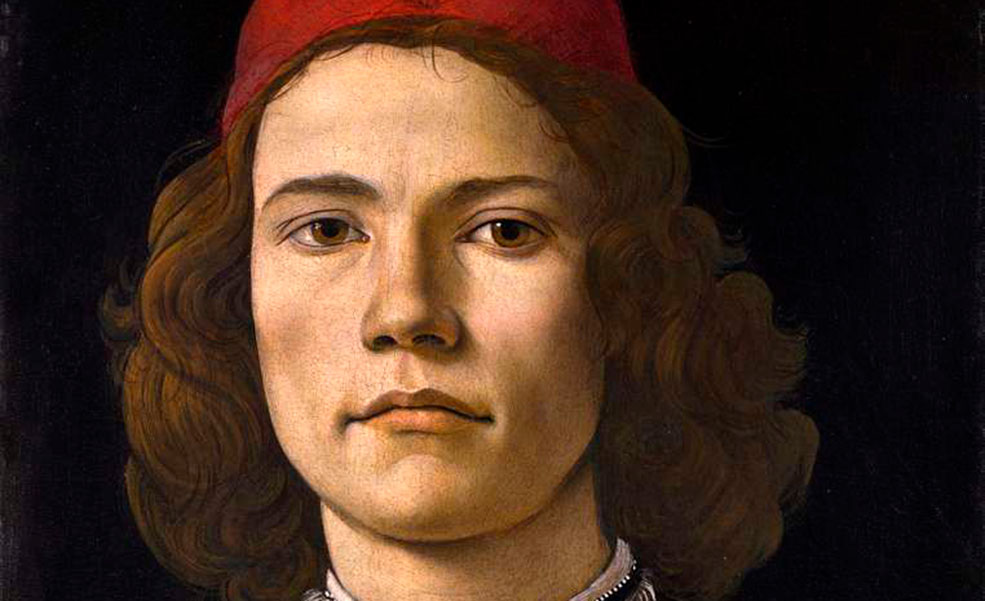

A symbolic painter of the Renaissance, Sandro Botticelli perfectly embodies the spirit and cultural values of late fifteenth-century Florence. A native of the city, he spent most of his life within the circle of Lorenzo the Magnificent and, through his works, breathed new life and unparalleled refinement into the art of his time.

A young Florentine: childhood and training of a fifteenth-century artist

The youngest of four children, Botticelli was born in 1445 to Mariano Filipepi and Smeralda, and grew up between the family home in Via della Vigna Nuova and the family workshop in the Santo Spirito district.

Mariano was a tanner and, though not wealthy, managed to provide decently for his family.

At a very young age, Sandro showed little aptitude for study and was sent to learn the trade with a goldsmith friend of his father, following the typical path of many Florentine artists of the time. In his Vite, Vasari reports that it was during these years that Botticelli began to show a certain talent for drawing and so, around 1461, he entered the workshop of the celebrated painter Filippo Lippi.

His second master was Andrea del Verrocchio, the illustrious artist who also trained Leonardo da Vinci. In the Madonna del Roseto, painted in 1470 and now housed in the Galleria degli Uffizi we can observe the fusion of the styles of these two great mentors: the chiaroscuro is bold and profound, a typical feature of Verrocchio’s workshop, while the soft, gentle face of Mary is an explicit legacy of Lippi.

Botticelli and the Medici

It was not until 1475, at the age of thirty, that the artist received his first commission from Lorenzo de’ Medici: a banner, now lost, depicting the goddess Minerva. The work was intended for Lorenzo’s brother Giuliano on the occasion of the Giostra di Santa Croce, described by the poet Agnolo Poliziano in his Stanze. It may seem a minor commission, but it enabled Botticelli to enter the Medici circle.

The Adorazione dei Magi

It was this new courtly environment that inspired his most famous paintings. Just a year later, he painted a large altarpiece for his new patrons: the Adorazione dei Magi (c. 1476, Florence, Uffizi). The work is a true glorification of the Medici family, with numerous members of the illustrious dynasty portrayed: Cosimo with his sons Piero and Giovanni as the Magi, and Lorenzo and Giuliano depicted among the crowd witnessing the offering of gifts.

A revolutionary painting: not only is the sacred scene imbued with political significance, with secular rulers as leading figures in a biblical episode, but the very structure of the work breaks with previous tradition.

For the first time, the Holy Family is placed at the centre, the apex of an imaginary pyramid with its base in the Medici and their acquaintances, following a frontal arrangement strongly opposed to the lateral perspective typical of medieval painting.

The Pazzi Conspiracy

Two years later, in 1478, came the darkest chapter in Medici history: the Pazzi, a family of bankers and long-standing rivals, plotted with the support of the pope, the Republic of Siena and other Italian lordships to wrest political control of the city from Lorenzo. On Sunday 26 April, during a mass celebrated in the Duomo by Cardinal Raffaele Riario, a young student from Pisa who had just been appointed to the role, the brothers Lorenzo and Giuliano were attacked in what soon became outright urban warfare. Lorenzo managed to escape, but Giuliano, unfortunately, was killed. The assassination was not well received by the Florentine people. Perhaps out of esteem for Lorenzo, or perhaps because of the blasphemous, sacrilegious act of a murder committed in a church, the crowd turned against the conspirators, who were executed one by one.

Botticelli was given the grim task of producing posters depicting the hanged rebels. These sombre effigies were displayed on the façade of Palazzo Vecchio as a warning. By then, Sandro was officially a trusted companion of the Magnificent.

Man and art at the centre of the cosmos

As time passed, Botticelli became increasingly integrated into the circle of intellectuals, artists and poets surrounding the Magnificent. The culture of the ruling class was strongly shaped by a renewed Neoplatonic philosophy, rediscovered thanks to the large number of Hellenistic Greek writings that had arrived in the West from Constantinople in the previous century. Botticelli was immediately captivated.

According to this vision, art and the artist are intermediaries between the world of Ideas, transcendent by definition, and physical reality. It was precisely these cultural influences that led Sandro to create some of his most celebrated works, such as Pallade e il Centauro (c. 1480–1485), an allegory of reason triumphing over animal instinct, today in the Galleria degli Uffizi.

The Nascita di Venere and the Primavera: symbols of Renaissance art

In the 1480s, Botticelli could be considered almost a court painter, though no formal court yet existed. The Medici exercised their influence over the city and Italian politics primarily through wealth and diplomacy, without any official title.

At this time, Sandro was sent to Rome along with a group of Florentine artists as a peace offering to Pope Sixtus IV, closely linked to the Pazzi Conspiracy, with the task of frescoing part of the Cappella Sistina.

This was a common practice for the Magnificent, who often sent his favoured intellectuals to other Italian courts. The aim was always the same: to demonstrate the cultural, economic and political supremacy of Florence and the Medici family.

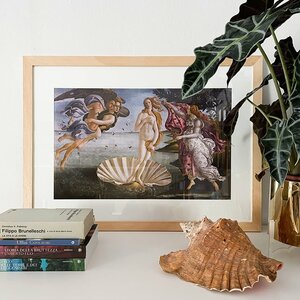

But it was around his return to Tuscany in 1482 that Botticelli painted the two works that most consecrated him as the emblem of Renaissance art: La Primavera and La Nascita di Venere, both now in the Uffizi. The first written record of these masterpieces comes from Vasari, who in 1550 described having seen them in the Medici’s Villa di Castello, owned by the popular branch of the family.

The two paintings, long considered “sister works”, show similarities but also clear differences, starting with their supports: the first on panel, the second on canvas. One is a profusion of flowers and mythological figures, the other presents an essential, almost abstract landscape.

La Primavera

With La Primavera, Botticelli created a true botanical catalogue of the flora typical of the Florentine hills at the time, perhaps drawn from the very garden of Villa di Careggi, where Lorenzo often hosted his circle of intellectuals and artists.

In the painting, at least 138 different species of different plants can be identified, all recognisable and absolutely real. Beneath the beauty of the composition lie deeply allegorical meanings. The artist most likely drew inspiration from a Stanza by his friend Agnolo Poliziano, which described a blooming garden with the Three Graces and Zephyrus chasing Flora, goddess of spring. In Botticelli’s version, three more mythological figures appear: the nymph Chloris, Mercury, Cupid, and at the centre, a splendid Venus, undisputed mistress of the garden.

La Nascita di Venere

A few years later, again in parallel with Poliziano’s poetics, Botticelli painted the greatest work of the time: La Nascita di Venere. Venus, once more at the centre, is shown covering her breast and pubis in the pose of the Venus Pudica, perhaps derived from an ancient statue already in the Medici collection.

To the left, Zephyrus and Aura, deities linked to air and winds, propel the goddess towards the shore, where one of the Horae awaits to drape her with a richly embroidered mantle. Botticelli is fully immersed in the metaphysical world of Ideas. The setting is ethereal, the light almost divine. Venus enchants with her marvellous face and flowing hair.

Here we see the fundamental hallmark of the Florentine artist’s works: the use of drawing as the sole instrument for composing scenes and characters. Everything, from colour to perspective, is subordinated to the outline. His figures, almost devoid of volume and mass, light and lacking physical depth, seem cut out by the fine contour line of his drawing; while the scenes and backgrounds are flat, as if the characters had been pasted onto a painted surface. Botticelli’s reality is deliberately abstract, detached from nature and immersed in a mental and imaginary dimension.

Artistic maturity, Lorenzo’s death and the spiritual crisis

Although Botticelli is best known for his pagan-themed works, his religious commissions should not be overlooked. Famous examples are the round panels Madonna del Magnificat and Madonna della Melagrana, painted around 1485 and 1487 respectively, today in the Uffizi. Especially in the former, the teachings of his beloved master Filippo Lippi are still evident. Mary is beautiful, though her face is melancholy, and the colours shine like precious gems. The scene is skilfully composed to fit the circular shape of the work, with curving bodies and the converging lines of the hands leading towards the book. Botticelli’s life and career could not have been better, yet the tranquillity of his beloved Florence was soon to be disturbed.

In the early 1490s, a stern Dominican friar arrived in the city. Girolamo Savonarola, from Ferrara, began to preach the need for cultural and spiritual renewal, denouncing the excesses of the Church and the city’s patrician families. Among his targets were also the arts and philosophy, judged too close to the pagan traditions of classical antiquity. The religious crisis began with ordinary citizens, home workers, and peasants dissatisfied with the rule of the powerful. Thanks to countermeasures taken by the Medici government, it did not spread entirely – at least until 1492, when Lorenzo the Magnificent died and the crisis engulfed the city. Just three days earlier, lightning had struck the Lantern of Brunelleschi’s Dome. The two events were immediately interpreted as divine omens: two years later, Piero de’ Medici was expelled from Florence and, urged on by Savonarola, the city proclaimed itself a Republic.

Tormented by his youthful works

Sandro Botticelli was deeply affected by the friar’s sermons and the events that overwhelmed his city. Faced with the bonfires of the vanities, when Savonarola’s followers burned objects, books and artworks deemed sinful, the artist developed a strong sense of guilt for the themes he had tackled in his youth. The last years of his artistic output were marked by extreme mysticism, perhaps an attempt to redeem himself in the eyes of God. The work that best represents this radical break with his past is undoubtedly La Calunnia, completed around 1495 (Florence, Uffizi).

The scene unfolds from the right, with King Midas, in the role of the unjust judge, seated on his throne while judging a half-naked man. Beside Midas, the allegories of Ignorance and Suspicion act as advisers. Opposite them, Envy precedes Slander, who drags the victim accompanied by the handmaids Treachery and Deceit. At the other side, an old woman, personification of Repentance, looks towards Naked Truth, who in turn raises her gaze to heaven, to God, the only source of Justice.

The painting, in total contrast to his youthful ideas, is an open critique of the ancient world, a world without God and therefore without mercy or true justice.

The solitude of his final years

At the dawn of the new century, Botticelli’s fame was in decline, overshadowed by a new generation of great artists such as Leonardo and Michelangelo.

Once esteemed by the city’s rulers, he spent the last years of his life in isolation and near poverty.

Sandro Botticelli died in Florence in 1510, at the age of sixty-five, leaving behind a legacy of works imbued with symbolic and allegorical meaning, full of fascination and mystery.

Cover photo: Self-Portrait, c.1483-1484, Sandro Botticelli, National Gallery, London, United Kingdom

Related products

Related museums

From €8,00

The Museo di San Marco began as a monastery of the Dominican friars around 1437 when Cosimo de’ Medici commissioned the architect Michelozzo to renovate the old complex building. The present building is a masterpiece of Renaissance art and houses a rich collection of works, in particular by Beato Angelico, who lived and worked here for most of his life.

Average visit time:

1 hour