If we wear wedges today, if our heels are comfortable, precious or simply colourful, we owe it to Salvatore Ferragamo. Born into humble beginnings, he conquered American celebrities and the global public with the bold originality of his footwear—an expression of rare and brilliant creativity. The Museo Salvatore Ferragamo is dedicated to the man and his creations, one of the most important and iconic figures in Made in Italy fashion.

The “shoemaker to the stars”, an ideal story

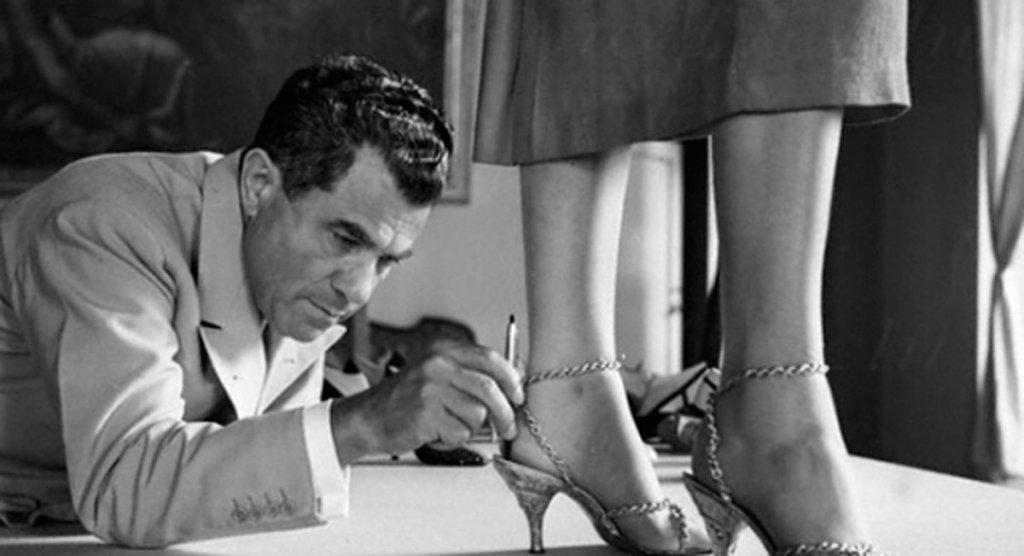

Salvatore Ferragamo’s story is one of talent, determination, and redemption. Born in Bonito—a small village near Naples—in 1898, the eleventh of fourteen children, he showed an overwhelming passion for shoes from an early age. Though his parents initially disapproved of shoemaking as too humble a trade, they changed their minds when, at just nine years old, Salvatore made his sister’s white shoes for her Communion overnight—shoes the family could not have otherwise afforded. His resourcefulness triumphed, and any resistance faded. He was sent to train with the local cobbler and then to Naples. A few years later, he left for America to join his older brothers. A brief stint in a Boston shoe factory allowed him to admire American production methods, though he remained convinced that Italian craftsmanship was unmatched. He then moved to California to open his shop, first in Santa Barbara, then in Hollywood. The budding film industry was the perfect stage for his creations. Success was immediate: from that point on, Ferragamo dressed the feet of stars like Greta Garbo, earning the nickname “shoemaker to the stars”.

In 1927, Ferragamo returned to Italy, choosing Florence as the base for his business. He knew well that the city had a long-standing and vibrant tradition of art and craftsmanship and sought to merge it with the entrepreneurial spirit he had gained overseas. America remained his key market, but the 1929 dollar crisis hit hard, and in 1933 he was forced to declare bankruptcy. Giving up wasn’t in his nature, and a few years later—with his sister’s help—he reopened his company in Palazzo Spini Feroni, a historic building that still houses the Archive named after him.

Hardship seemed only to fuel his inventive spirit, and it was between the 1930s and 1940s, against the backdrop of World War II, that some of his most revolutionary and iconic creations emerged. This was also the period of his marriage to the beloved Wanda Miletti, with whom he had six children.

Official recognition soon followed. In 1947, Ferragamo received the prestigious Neiman Marcus Award (the fashion world’s equivalent of an Oscar) in Dallas and took part in key industry initiatives, such as the first Italian fashion exhibition in 1951. By the end of the decade, his autobiography, Il calzolaio dei sogni (Shoemaker of dreams), was published in London, where he claimed to have created 20,000 shoe designs and filed 350 patents over his forty-year career.

Today, thanks to recent and meticulous research, we know that documents in his name number 386, ranging from footwear (especially women’s) to entirely different objects, including military devices—testament to a versatile mind capable of turning any idea into innovation.

Aesthetics, taste and functionality

Shapes, materials, surfaces—there wasn’t an aspect Ferragamo didn’t explore. His shoes are works of art and high craftsmanship, meant to be centrepieces rather than mere accessories, starting with colour: for the first time in modern history, uppers and heels featured bold, vivid tones. This may stem from his southern Italian childhood or the Mexican culture he encountered while living in California.

His work constantly merged past, present and future, drawing inspiration from Renaissance masterpieces in Florence as well as from contemporary innovations (in art, design, architecture, and interiors), his travels to the East, and collaborations with other prominent designers, such as Elsa Schiaparelli, an Italian who became a naturalised French citizen. These direct and indirect influences were absorbed and combined with a unique sensitivity, allowing him to follow—and often anticipate—fashion trends by years.

Thus was born the “vertical zigzag” heel covering made from pieces of mirror reminiscent of mosaic art (1929); or the 1930 pull-over shoe (without laces or fastenings), with a pyramid heel inspired by the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb; or the “labyrinth” embroidery with geometric motifs—somewhere between Cubism and African tattoos—patented in 1931.

On the feet of film stars and nurses

As a true designer, Ferragamo prioritised functionality before aesthetics. While in the United States, he took an anatomy course to fully understand the structure of the foot and discovered that the arch needs support for true comfort. This led him to invent the cambrione, a very thin metal plate placed inside the sole between the toe and the heel, to support the arch.

Among his patents is also the Tramezza construction, which inserts a thin leather layer between the sole and insole, capable of “remembering” the foot’s shape to make shoes more comfortable. Other inventions include single-piece leather uppers and invisible stitching techniques, as seen in the famous “gloved arch” shoe: soft as a glove, its stitching is hidden beneath the sole in the gap between front and heel.

His shoes were so comfortable that Maria José of Savoy—wife of the last King of Italy and head of the Voluntary Red Cross Nurses during WWII—decided to order them for all the nurses after trying them herself.

Timeless models of elegance and ingenuity

Challenges fuelled Ferragamo’s creativity, leading him to ingenious and original solutions. During the period of autarky, when resources and technologies were scarce, he began fervent experimentation. In the absence of steel to make heels, he decided to use wine corks sewn together and covered in leather: the wedge was born. Later shaped in endless variations, decorations and colours, it became the hallmark of his success.

Material cross-pollination was at the core of Ferragamo’s method: he transformed humble materials—straw, raffia, even sweet-wrapper cellophane—into luxurious shoe weaves. Shaped like an “F” (his surname’s initial), the Sandalo Invisibile (Invisible Sandal), with a transparent nylon upper like fishing line, won him the 1947 Neiman Marcus Award.

His trip to Japan inspired the Kimo (1951), a high sandal with openwork in kidskin, complete with a snug, interchangeable inner shoe in various colours, reminiscent of traditional Japanese tabi. Native American footwear inspired the “shell sole” (1959), which folded upwards to wrap around the foot. He also created a metal-thread heel, an 18-carat gold sandal (one of Ferragamo’s most precious pieces), the 11-cm stiletto heels for Marilyn Monroe, who ordered them in all colours and materials—creations of astonishing charm and modern appeal.

Are you interested in articles like this?

Sign up for the newsletter to receive updates and insights from BeCulture!

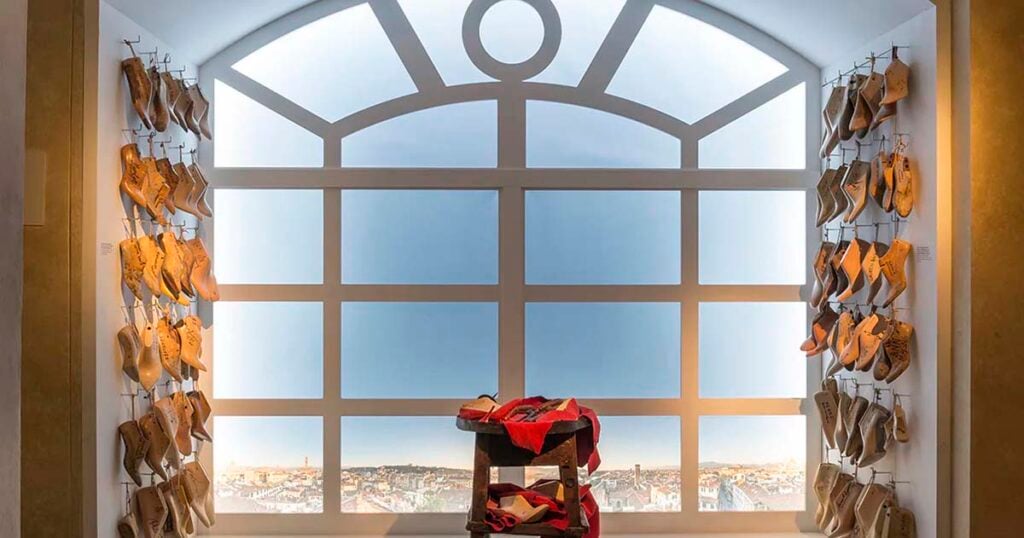

The Ferragamo Museum

Salvatore Ferragamo passed away in 1960. Since then, the business has been carried on by his wife and daughters. The Salvatore Ferragamo Museum, founded by Fiamma Ferragamo in the mid-1990s, tells the story of this great designer in an ongoing dialogue with art, architecture and the disciplines of his time—and ours. It was the first green museum in Italy and has received international recognition for its cultural commitment and significance.

Even if fashion is not your passion, the Museo Salvatore Ferragamo will captivate you with his story and the boundless skill of Italian craftsmanship when guided by extraordinary talent.