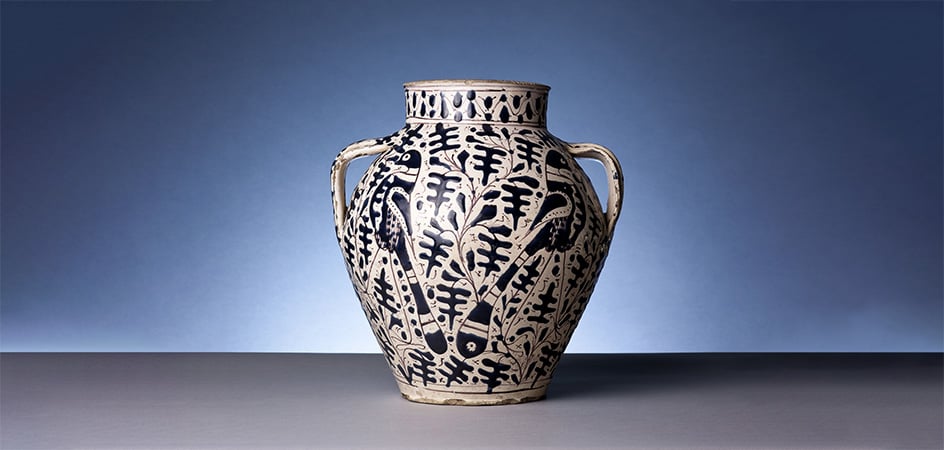

Human beings have always shaped the earth: clay, water, air and fire are the ingredients of an age-old tradition born for practical purposes but soon enriched by aesthetic intentions. Since antiquity, vases and other containers have been decorated with ornamental motifs, mythological stories, allegories and graphic elements reflecting the tastes of their time. On occasion, they even become symbols of an era, as happens during the Renaissance, when Italian maiolica is no longer associated merely with tableware but becomes a true collector’s item. Throughout the sixteenth century, the art of tin-glazed pottery evolved in its techniques, forms and style, giving rise to astonishing creations—remarkable in their beauty, variety and craftsmanship—that still captivate viewers today.

What is maiolica and where does the name come from?

Maiolica is a type of ceramic coated with a tin-based vitrifying glaze which, when applied to the so-called biscuit—the clay piece after its first firing—whitens the naturally reddish surface. This allows it to be painted with polychrome decorations, using pigments derived from the same vitreous base: blue from cobalt, green from copper, brown-violet from manganese, and so on. A second firing is needed to fuse and fix the glaze and colours.

To increase brilliance, artisans could also use the lustre technique, which required an additional treatment and a third firing.

In Italy, references to tin glazing appear in a fourteenth-century alchemical treatise, and it is known that tin was widely used in sixteenth-century workshops—so common, in fact, that it gave rise to the saying “piombo todesco e stagnio fiandresco” (“German lead and Flemish tin”), referring to the flourishing Dutch trade in high-quality English tin. However, the production process for maiolica was already known in the Islamic world during the Middle Ages. The term maiolica (or majolica) actually derives from Majorca, the Spanish island—then under Islamic rule—from which Moorish potters exported their creations. The iridescent, orientalising motifs were soon imitated by Italian ceramicists who, over time, developed their own stylistic autonomy.

The Early Renaissance: the golden age of Italian maiolica

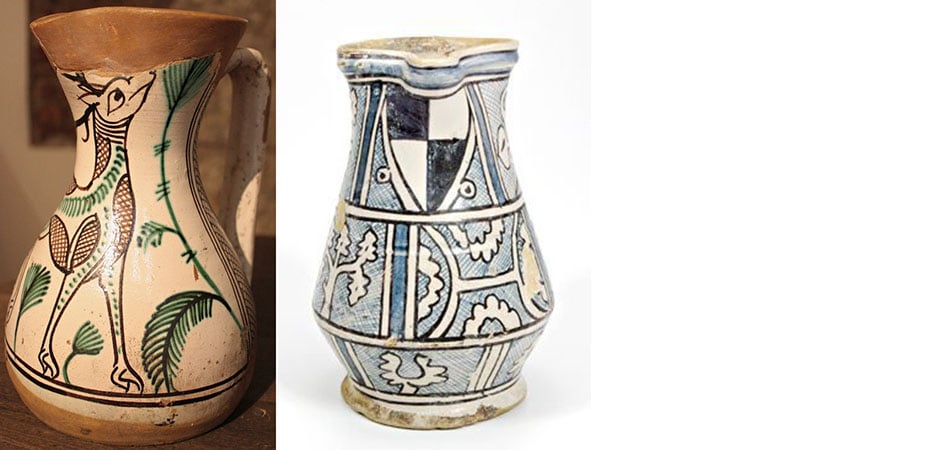

Maiolica was produced in several areas across the peninsula, especially in central-northern Italy and in the south. Among the traditions preceding the glorious sixteenth century, the so-called archaic maiolica of Faenza, Pisa and Orvieto is particularly noteworthy, characterised by brown-manganese and copper-green bichromy. Vases, plates, bowls, albarelli and jugs were decorated with human, animal and plant figures, as well as with epigraphic and heraldic motifs often associated with powerful local families.

The true turning point, however, came at the beginning of the fifteenth century, when a new, more opaque and brilliant glaze was developed and the colour palette became richer and more vibrant. This creative evolution paralleled the growing demand for high-quality objects among the aristocracy and the affluent bourgeoisie.

Decorative motifs and typical features

The Early Renaissance boasts a rich vocabulary of styles and decorative families: flowers and foliage inspired by Gothic, Byzantine and Oriental traditions, as well as increasingly naturalistic zoomorphic and anthropomorphic figures.

Typical of Faenza—one of the major production centres of the time—are the patterns palmetta persiana and penna di pavone (or Pavona). The latter, made up of polychrome bands reminiscent of the peacock’s plumage, is said to have been created as a tribute to Cassandra Pavoni, the young lover of the city’s lord.

Human presence appears most notably in the profiles of the so-called “belle donne”, an amatory genre in which an idealised portrait of the beloved was painted on ceramic pieces of tableware gifted by the groom at the time of the wedding as a symbol of female virtue.

Beyond dining ware, maiolica was also used to decorate horizontal and vertical surfaces—floors, walls and plaques.

An exhaustive example of this usage and of the many ornamental themes of fifteenth-century maiolica is the pavement of the Vaselli Chapel in San Petronio in Bologna, created in 1487 by Pietro Andrea da Faenza and other craftsmen. A “carpet” of brightly coloured hexagonal tiles featuring a complete repertoire of motifs: from the Persian palmette to the peacock feather pattern, the curled Gothic leaf and various allegorical figures. Of particular interest are the signature and self-portrait of the master maiolica maker, shown engaged in the craft of producing tiles.

Although considered a minor branch of production, small plastic sculptures were also made, whether everyday objects or decorative pieces, depicting scenes drawn from the moralising, mythological and courtly repertoire typical of the period. Among the most exquisite examples is the calamaio con la scelta di Paride from the Museo di Faenza: on the left, the Trojan hero appears lost in a dream, while Mercury raises the apple of discord behind him, and the three rival goddesses — Venus, Juno and Minerva — wait on the opposite side, dressed in Renaissance clothing and hairstyles.

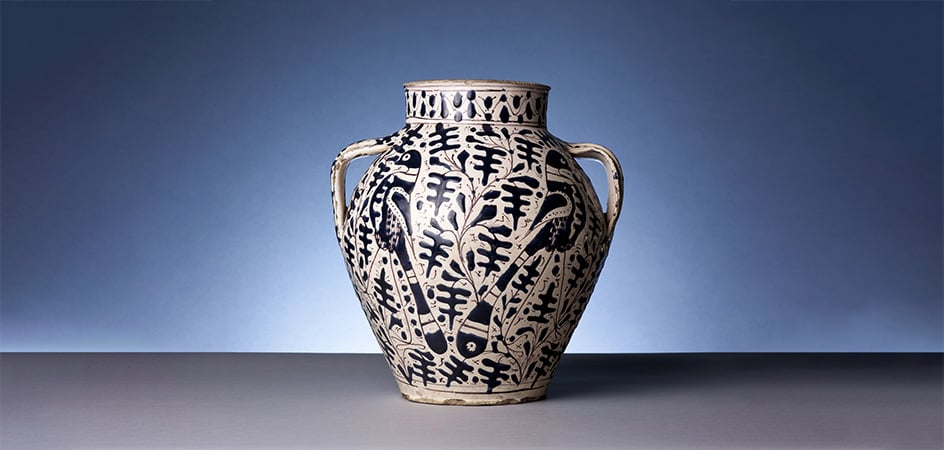

Finally, among the common techniques of the period, one should also mention zaffera a rilievo, a type of workmanship widespread in Romagna and Tuscany that gives the pigment a distinctive raised, plastic quality. Particularly noteworthy, for its shape and craftsmanship, is the orciolo preserved in the Museo Nazionale del Bargello in Florence.

The sixteenth-century triumph of the applied arts

The mature Renaissance, with its appetite for opulence and “anticaglie” (whether genuine, presumed or imitated, and the very foundation of many Wunderkammer), embraced lustre maiolica with enthusiasm. This technique imparted a metallic — and therefore precious — iridescence to ceramic objects. Florence, Deruta, Gubbio and certain areas of Lazio distinguished themselves, alongside the centres already mentioned, for their abundant and refined production, which was receptive to contemporary pictorial developments and capable of evolving into a variety of decorative motifs.

The “istoriato” style

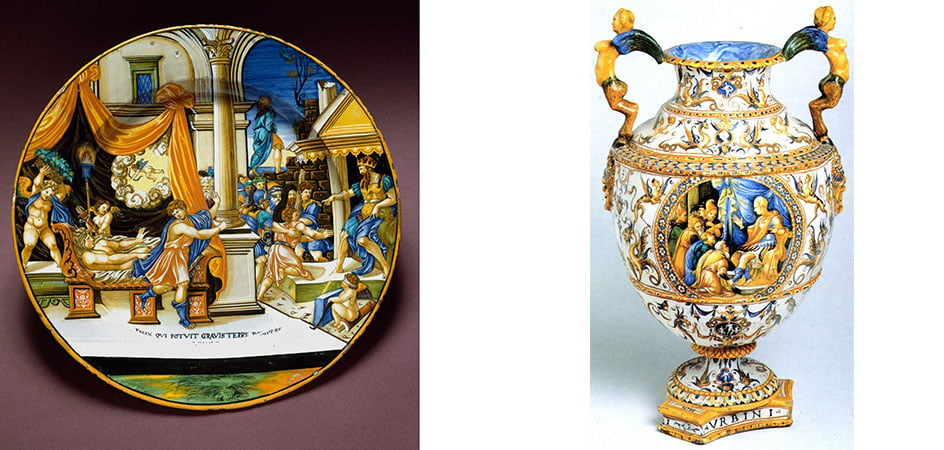

Fine plates, vases and bowls became ideal supports for depicting biblical, mythological and Roman-historical episodes in a genre that would come to be known as “istoriato”. The narrative is detailed and, over time, increasingly dense and dominant: the scenes cover the entire ceramic surface, leaving little or no empty space. The graphic models were drawn from illustrated books and woodcuts and, with the growing influence of Raffaello’s painting, also from the works of the great master from Urbino.

Dating from the first half of the sixteenth century, for example, is the plate signed by Francesco Xanto Avelli — one of the most skilled masters of the genre — now in the Museo del Bargello, depicting a Raphaelesque subject: Joseph the Hebrew. He is shown fleeing the advances of Potiphar’s wife, as the inscription below reads: “Happy is he who breaks the heavy bonds of earthly ties.” The moral continues on the reverse, which warns: “The wise man who keeps his desires modest does not entangle himself in those snares that so often make the lives of others appear burdensome.”

Are you interested in articles like this?

Sign up for the newsletter to receive updates and insights from BeCulture!

“Raphaelesque” grotesques

Another achievement attributed to Raffaello is that of bringing thegrotesque motif to full maturity. These fanciful decorations, dating back to the Roman period and often inspired by the natural and animal world, had been rediscovered in the Domus Aurea at the end of the fifteenth century and were already being adopted by various artists, including Botticelli, Perugino, Signorelli, Pinturicchio and Ghirlandaio.

It was Raffaello and his workshop, however, who further developed this classical theme into new and freer forms — developments that also influenced ceramic production. Branches, leaves, festoons and imaginary creatures thus entered the repertoire of sixteenth-century maiolica, with results of great compositional liveliness.

The Bianchi di Faenza

In contrast to the opulent and densely populated “istoriato” style, from the second half of the sixteenth century and throughout the following one another aesthetic emerged — very different in appearance yet equally theatrical. The so-called “Bianchi di Faenza” (or faïence, as they were known in Europe) take their name from their city of origin and from their distinctive white ground. The decorations are smaller in scale and more restrained in colour, while the painterly stroke is quick and fluid. This essential and elegant line — compendiario, in academic terminology — is enhanced by varied and daring plastic forms, with intricate piercings and lace-like effects. It was precisely this style, with its measured yet vibrant touches of colour, that ensured greater continuity for Italian ceramic production in European courts, which were eager to acquire the creations born from the imagination and artistic skill of Mediterranean master potters.

The Renaissance period certainly does not exhaust the history of Italian maiolica, but with its variety and exuberance it undoubtedly represents its peak. This is proof that the so-called Minor Arts — such as ceramics, goldsmithing and evenminiature painting — are “minor” in name only, not in substance.