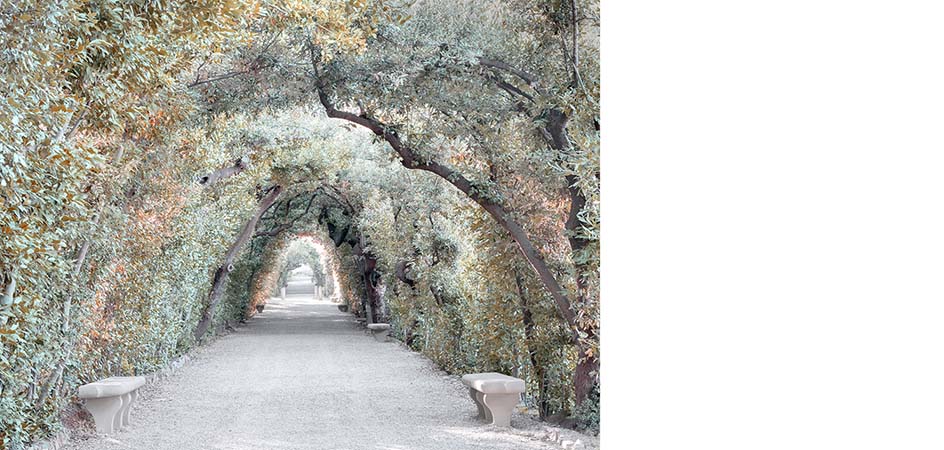

“The photographs are deliberately meant to allude, with a touch of irony, to a postcard-like dimension as a defence mechanism against the erosion imposed by globalisation.” This is how Francesco Jodice, an internationally renowned artist, comments on the snapshots taken in 2023, when he won the Orbital Cultura Award and had the opportunity to capture some of Florence’s most important heritage museums.

We met him to learn more about this experience and his artistic vision.

The Orbital Cultura Award and Jodice’s encounter with Florentine museums

Born in Naples in 1967, Francesco Jodice graduated in architecture and now lives in Milan. At the heart of his research lies the relationship between cities and communities, geopolitics, and the new phenomena of megapolitics. Interests that he develops through a multifaceted practice spanning photography, video and installations. The very purpose of the Orbital Cultura Award is the commission of a photographic project – with an award of €10,000 – in collaboration with miart, the International Modern and Contemporary Art Fair. Its aim is to provide Italy’s historic museums with contemporary, high-quality images, fostering an ongoing exchange of perspectives between past and present. The edition inaugurated by Jodice (represented by the galleria Umberto di Marino) was dedicated to the Gallerie degli Uffizi, comprising the museo degli Uffizi, Palazzo Pitti, the Giardino di Boboli and the Corridoio Vasariano .

“I tried to free four totemic places of the city from the convulsions and wear of daily life,” Jodice declared at the award ceremony. “I sought to take these spaces out of their contingent time, releasing them from the obligation to participate in the ritual of mass tourism.”

This unprecedented interpretation – as often in his work – managed to reconcile the needs of the commission, adopting the documentary objectives of the Award while combining them with personal artistic intentions.

The project and the dialogue with the “giants” of Italian culture

Urban landscape is a recurring theme in Jodice’s work, and it is not the first time he has engaged with leading museum institutions. One need only think of his 2012 project Prado. Spectaculum Spectatoris: a photographic investigation into the relationship between viewers and works of art. Yet approaching historical, iconic and visually overexposed buildings such as the Florentine museums and offering a personal vision of them is no simple challenge. “I approached these totemic monuments of Florentine history and art history not as architectures, but as bearers of legacies that are traversed every year by millions of travellers, often insufficiently equipped to grasp their depth and stratification,” he explains. “I attempted to convey a schizophrenic sentiment: cultural artefacts coming from the distant past but animated by the urgency of repositioning themselves every time history moves forward.”

A short circuit, then, between a cumbersome past and a present eager to assert itself without losing its heritage.

The risk, however, according to Jodice, is becoming prisoners of an outdated identity, crushed by the consumerist frenzy of modern travellers. “The administrations responsible for managing the narrative of Italy’s immense artistic, architectural and landscape heritage are often burdened with the need to confirm an image of this heritage frozen in time, as sometimes it is thought dangerous to turn the page and set a new, alternative narrative.” Thus, the constant need to sustain historical and cultural greatness becomes an obstacle to the true expressive power of what museums and galleries strive to highlight.

A paradox, especially considering that “masterpieces are timeless and eternalised: they do not follow fashions or customs but renew themselves and constantly possess the authority to produce new meanings in relation to the changing times.”

In this, Florence is both a master and a poor example. According to the artist, it is a marvellous city endowed with a millenary history, yet compromised by a corrupted image. “A tiny city that you could cross in a day and yet a lifetime would not be enough to comprehend its history.” And he continues: “Florence and its monuments, its art, its storytellers and its histories make me think of Walt Whitman and the verse of his poem: “I contain multitudes.”

But how then to approach such multiplicity, rich in both fascination and contradictions?

“I don’t believe in archives, warehouses, or image repositories”

At this point, we ask Jodice how, in practical terms, he carried out his work for the Orbital Cultura Award and how he managed to achieve that effect of suspension, beyond time and space, that emanates from his photographs. “I am a cold artist in procedure and a poor flâneur,” he confesses. “Most of the time is spent defining the meaning I want to attribute to works and projects. Once this methodological aspect is clarified, the executive part is very simple: it is about giving visible form to the idea.”

Once the conceptual line is set, he moves on to practice, which always takes place in a measured manner: Francesco does not believe in accumulation but rather in the pinpoint precision of a single essential work. “I am also very sparing when it comes to the need to produce further unnecessary images or photographs. I prefer to spend several days creating a single photograph, perhaps through micrometric corrections, rather than taking many images to review later.”

A way of working consistent with his way of thinking and reading the present time, especially in terms of consumption. “In general, I believe there is an acceleration of enjoyment,” he reflects. “It seems to me that tourism has become a kind of performance: to go to as many places as possible and try to see everything that we are dogmatically told is essential. We should relearn to travel as something slow and ruminative, unsystematic and askew, to observe in a colour-blind way compared to the dominant gaze.”

Are you interested in articles like this?

Sign up for the newsletter to receive updates and insights from BeCulture!

The role of photography in narrating Italy’s artistic heritage

And is that what photography is for? “Photography, painting and art are the same thing,” he states. It sounds like a provocation, but it is not. All of them, in his view, force us to confront our prejudices, to recognise them and to question them. This is why, rather than a means of representing reality, photography is a way to “cultivate doubts and formulate questions with precision and pertinence.” A kind of training ground for exercising independent thought, even when the subject is works and places already ingrained in our imagination and apparently devoid of possible questions.

This, at least, is the direction that guides his intellectual and creative practice today.

But we are curious to know how he sees – as a lecturer at NABA in Milan, working with young talents – the photography of tomorrow and where it might go: “I have no idea, and that excites me.”

Before parting, we ask Jodice one last question: what does it mean to him to contribute to the promotion of Italian culture also through projects such as the Orbital Cultura Award?

“Theodor W. Adorno said that the task of art is to bring chaos into order. I am an artist.”