It is well known that artists are often able to detect and interpret a shared feeling before it becomes widely recognised. This is precisely what happened with the Avant-garde movements of the 20th century: a succession of cultural movements which, in the early years of the century, gave voice to a widespread and stirring unease, irreversibly shaping the course of art and history.

The origins of the Avant-garde movements

The twentieth century opened in Europe as a time of profound change: the bourgeois society of the Belle Époque, rooted in the nineteenth century and marked by its surface-level splendour, was shaken by new social and economic forces which, among other things, led to the consolidation of a new popular class. Scientific discoveries, rapid industrial development, and new philosophical and psychological theories all pushed towards a new dimension, marked by uncertainty and apprehension. A true revolution on multiple levels, and intellectuals of the time (artists, but also musicians and writers) confronted it with almost combative intensity. The word “avant-garde” itself comes from political and military terminology, indicating the soldiers at the front line, approaching the enemy ahead of the main troops.

Animated by this fighting spirit, the artists advanced towards modernity, determined to break every bond with the past – particularly with the recent legacy of the Impressionists, who had privileged vision and external reality, captured in its shifting atmospheres and light conditions. Art became the place to give space, form, and colour to inner feeling, to what stirs and unsettles the spirit. The results were revolutionary and took shape through different movements, among the most significant: Expressionism, Cubism, Futurism, and Dada.

Are you interested in articles like this?

Sign up for the newsletter to receive updates and insights from BeCulture!

Expressionism: from the Fauves to Die Brücke

What we today call Expressionism can be divided into two currents, similar in intention but different in outcomes and geography. The first includes Henri Matisse, André Derain, and Maurice de Vlaminck, who exhibited their works at the Salon d’Automne in Paris in 1905, scandalising critics. They earned the derogatory nickname Fauves (beasts in French) because of the intensity of their colours and the forceful handling of paint. Their aim was to depict the world not as it appears, but as it is perceived, rejecting the formal and compositional principles of Neoclassicism and Romanticism. The result is a painting style made of simplified and distorted forms, full and empty planes, dynamism, and strong contrasting colours. The Dance by Matisse – in its 1909 version (MoMA, New York) and especially in the 1910 version (Hermitage, St Petersburg) – is widely considered the most representative masterpiece of French Expressionism.

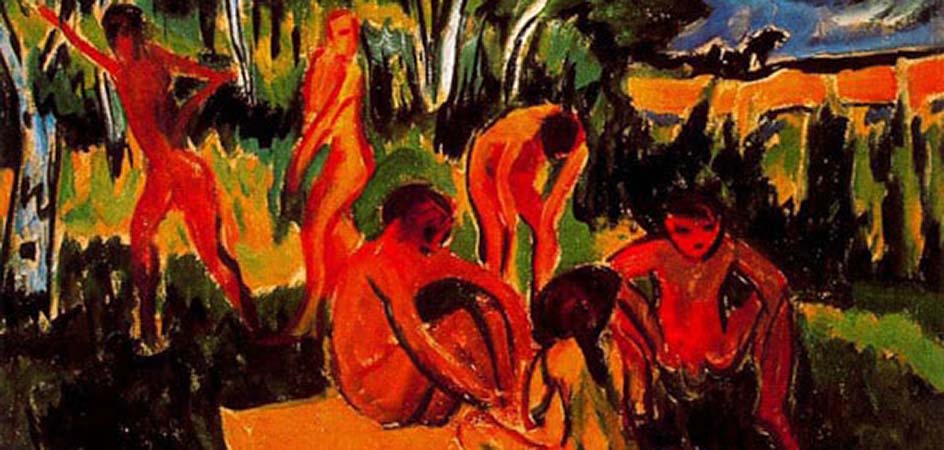

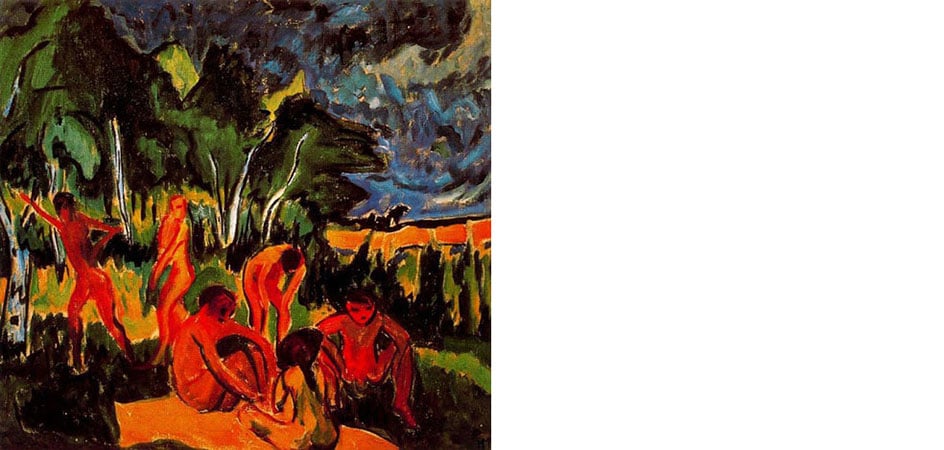

Meanwhile in Germany, at around the same time, Die Brücke (The Bridge), a similar movement, emerged in Dresden in 1905, later moving to Berlin. Its members – Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Erich Heckel, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff and Fritz Bleyl (architecture students at that time), and later Max Pechstein, Emil Nolde and Otto Müller – openly distanced themselves from Impressionism and Post-Impressionism and instead revived the German Gothic tradition. Another source of inspiration was the so-called “primitive” art of non-European cultures: German artists looked to the masks and ritual objects arriving at the time from Africa and the Pacific Islands, interpreting them as symbols of a forceful, clear and anti-academic visual language. Not by chance, their earliest works were woodcuts (xylographs), a technique that had been almost forgotten yet remained highly expressive. For them, as for their French counterparts, the extreme stylisation of figures was the result of projecting the inner self, a search for freedom that rejected perspective and embraced subjectivity. Recurring themes include nudes, natural and urban landscapes, though with a palette – and therefore a tone – that is darker and more unsettling than the Parisian one. Plein air, a 1910 canvas by Pechstein (Duisburg, Wilhelm-Lehmbruck Museum), is a perfect example.

Cubism

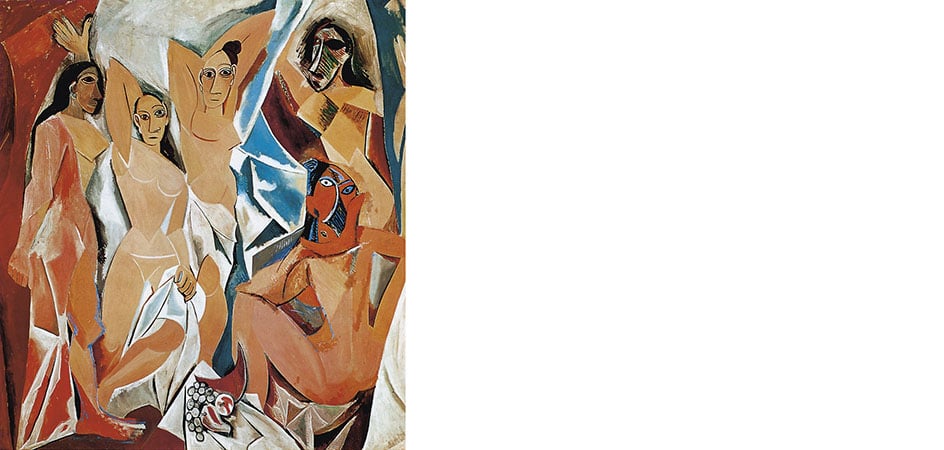

The term Cubism was coined in 1908 by critic Louis Vauxcelles – the same who had named the Fauves – in reference to works by Georges Braque, which he claimed were made of “cubes”. However, it is Les Demoiselles d’Avignon by Pablo Picasso (1907, MoMA, New York) that is commonly regarded as the manifesto of Cubism, founded by the French-Spanish duo. Although still in embryonic form, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon – which depicts a group of prostitutes in a brothel in Avignon, each shown from different viewpoints compressed into a single two-dimensional space – already contains the key principles of the movement: the angular, linear rendering of volumes, the direct reference to the art of Cézanne and to African sculpture, and the departure from a mimetic, faithful reproduction of reality.

Over time, Cubism evolved, and so did its phases. The formative period (1907–1909), during which this new language took shape and it was still difficult to distinguish Picasso’s hand from Braque’s; the analytical cubism phase (c.1910–1912), characterised by an increasingly pronounced fragmentation into ambiguous geometric forms; and finally synthetic cubism (c.1912–1914), which introduced elements taken from the external world – actual fragments and collage – thus going beyond the two-dimensional limits of the canvas. In this phase, the disruption of external reality reached its highest expression: the viewer is directly called upon to reassemble it, to reconstruct the perspective planes (abolished by the artists), and to “read” the work mentally, almost literally, through words and pieces of newspaper.

Futurism

A new and equally powerful impetus also swept through Italy, though with a markedly different character from the developments across the Alps: Futurism. The poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti proclaimed its birth when, on 20 February 1909, he published the Manifesto Futurista in the French newspaper Le Figaro. Futurism presented itself as a far-reaching socio-cultural programme, poised to infiltrate literature, art, architecture, music, theatre, and cinema. Though it pre-dated Fascism, post-war Futurism came to share several affinities with Mussolini’s political ideology, such as fervent patriotism, interventionism, and the exaltation of violence and war as instruments of change.

The work of Umberto Boccioni, Giacomo Balla, Carlo Carrà, Luigi Russolo, and Gino Severini – to name but a few – revolves around a fascination with modernity and the rejection of the past (hence the name ‘Futurism’); with technological progress, the urban environment, and electric light; and with the allure of speed and dynamism. Their relationship with Cubism is, particularly in the early stages, quite explicit and can be traced to the time several Futurist artists spent in Paris.

Light and movement are central to Futurist thought, whether in painting or sculpture: Forme uniche nella continuità dello spazio by Boccioni (1913, Milan, Museo del Novecento) is considered one of the masterpieces of Futurism, achieving a simultaneous, material fluidity that renders the figure somewhere between human and machine. The viewer witnesses the figure in the process of becoming, the unfolding of action through space.

Dadaism

It was precisely the Futurist soirées that the Dadaists looked to when, in 1916 in Zurich, they founded the Cabaret Voltaire, a meeting place and performance venue defined by its anti-conformist spirit. And Dada was indeed anti-conformist, starting with its very name which, according to legend, was chosen by randomly opening a French–German dictionary. The French word dada (meaning rocking horse) seemed perfectly suited to the group of artists, who adopted it as an emblem for their anti-aesthetic creations and acts of protest, born from their disgust for bourgeois values and their rejection of the First World War. A clear refusal of art in its traditional sense is what unites Jean Arp, Richard Hülsenbeck, Tristan Tzara, Marcel Janco and Emmy Hennings in their photomontages, collages and other works created from found or repurposed materials.

The European Dada movement soon found its counterpart in the United States, led by the French-born, later American, Marcel Duchamp, and marked by a more ironic and subversive spirit. It was within Dada that the ready-mades emerged: ordinary, commonplace objects, removed from their usual context and elevated to the status of works of art. This concept was destined to revolutionise twentieth-century art, with far-reaching ideological and formal consequences. Duchamp, along with Man Ray and Francis Picabia, questioned the very meaning of art itself, challenging the system from within. Fontaine is, in this regard, an emblematic case: created by Duchamp in 1917, it is an ordinary urinal, turned on its side and signed with the initials of his pseudonym (R. Mutt). The work was submitted to an art exhibition, which refused to display it. It subsequently disappeared, surviving only in a single photograph taken by Alfred Stieglitz, photographer and gallery owner, and a friend of Duchamp. The versions we see in museums today are replicas that Duchamp authorised in the 1950s, once the art world had finally become ready to understand them.

All of the historical Avant-garde movements discussed here – and those we regret having had to leave aside (such as Wassily Kandinsky’s Abstract art and André Breton’s Surrealism) – contributed in an extraordinary way to the cultural history of the West. Their theoretical foundations and practical achievements have influenced, and continue to inspire, generations of artists and intellectuals, with ideas that remain as relevant and disruptive as ever.If this reading has sparked your curiosity, we recommend a trip to Verona to visit Palazzo Maffei: its rich and evocative collection offers a comprehensive overview of the variety of approaches and solutions explored by the artists of the Avant-garde.